As Netflix turns 20, let’s revisit its biggest blunder

We all have those moments we’d rather forget. Let’s revisit one of Netflix’s on the 20th anniversary of its launch.

We all have those moments we’d rather forget. Let’s revisit one of Netflix’s on the 20th anniversary of its launch.

The streaming-video behemoth, which upended nearly every aspect of the movie and TV businesses over its two-decade history, may seem unstoppable now. But in 2011, its ambitions nearly spelled its demise.

The online-video service, which started out renting DVDs by mail, was three years into experimenting with on-demand streaming and CEO Reed Hastings knew it was the future. With streaming video, Netflix could bring movies and TV to the world, as it started to do in 2010 in Canada, the first country Netflix entered outside the US. (Today, it is nearly everywhere in the world.) However, Hastings ran before he could walk when he abruptly announced in July 2011, against better counsel (paywall), that Netflix would splinter its DVD and streaming subscriptions.

Instead of paying $10 a month for DVD rentals and unlimited on-demand streaming, customers who wanted both services would have to pay for two different packages, each starting at $7.99, or $15.98 for the pair. “With this change, Netflix will no longer be offering unlimited plans that include both streaming and DVDs by mail,” Netflix unceremoniously announced in a release on July 12.

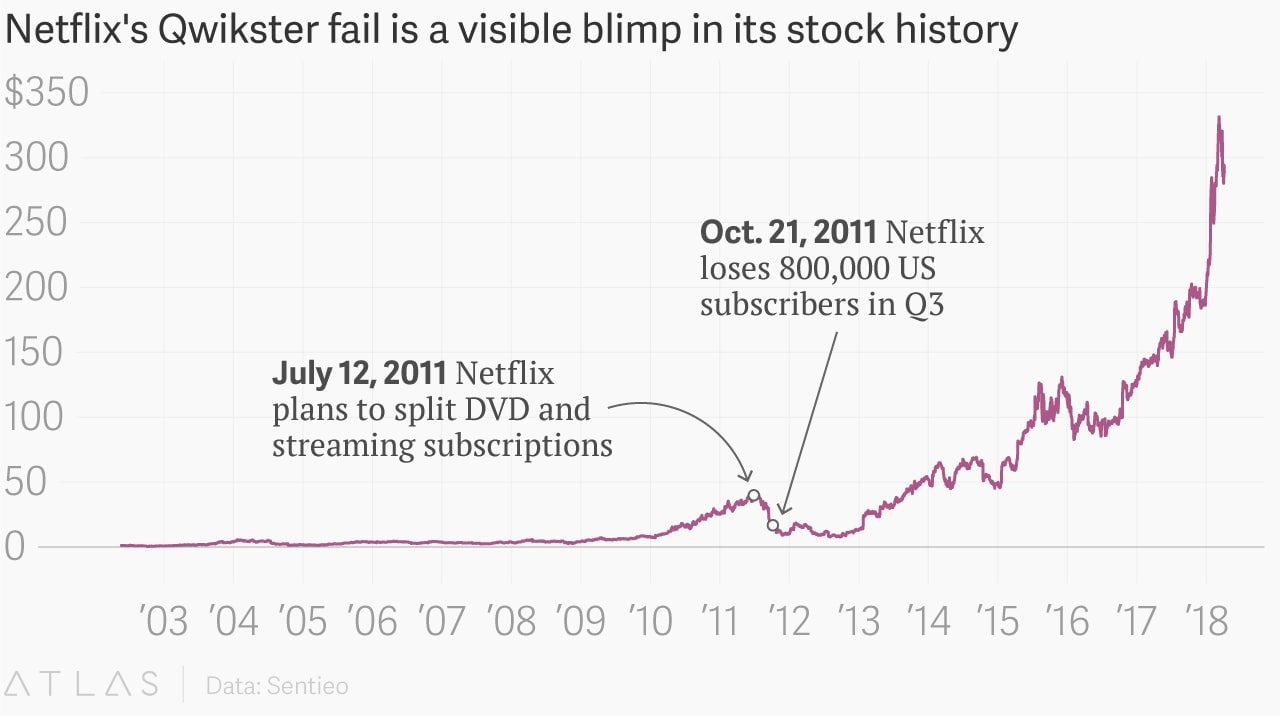

At first, the stock rose to an all-time closing high of $42.68, with investors drawn to the additional revenue per subscriber the move might produce. The stock wouldn’t reach that level again for more than two years. Subscribers swiftly expressed their displeasure about having the DVD rentals that attracted them to Netflix removed from the convenience of on-demand streaming. The dual plans effectively amounted to a 60% price hike.

After two months, during which Netflix’s stock lost half its value, Hastings addressed the issue in a blog post that apologized for the way the strategy was announced—and then doubled down on the plans. The Sept. 18 post began:

I messed up. I owe everyone an explanation.

It is clear from the feedback over the past two months that many members felt we lacked respect and humility in the way we announced the separation of DVD and streaming, and the price changes. That was certainly not our intent, and I offer my sincere apology.

It went on to say that the DVD service would soon be called Qwikster.

We realized that streaming and DVD by mail are becoming two quite different businesses, with very different cost structures, different benefits that need to be marketed differently, and we need to let each grow and operate independently. It’s hard for me to write this after over 10 years of mailing DVDs with pride, but we think it is necessary and best: In a few weeks, we will rename our DVD by mail service to “Qwikster”.

The site’s login credentials, billing, ratings and reviews would not be integrated into the streaming service’s, the release added. So if a customer with both services needed to change their billing or contact information, they’d need to do so in two places. And their ratings and reviews on Qwikster would not show up on Netflix, and vice-versa.

The move did nothing to calm customers and Netflix cancelled plans for the service less than a month later, while leaving the DVD and streaming plans separate. “There is a difference between moving quickly—which Netflix has done very well for years—and moving too fast, which is what we did in this case,” Hastings said in a statement. The whole ordeal cost the company about 800,000 US subscribers in the third quarter of 2011, its first decline in years. For years afterward, planned rate increases made investors skittish.

Netflix ultimately learned from this youthful blunder and got smarter about the way it hikes prices. Last time it raised rates in the US, it signed up more new subscribers than ever, because the increase was modest and imposed during a quarter that also included the return of some of its hottest shows such as The Crown, Stranger Things, and Black Mirror, and new releases like Bright and Mindhunter. It now has 117 million streaming subscribers worldwide, up from the 24 million or so total members it closed out the third quarter of 2011 with. The DVD business lives on, with about 3.4 million subscribers at last count.