Be the last active investor standing

Of all the debates in capital markets today, there probably isn’t one that’s more heated than the roles of active and passive management in the years ahead. But there’s a story within the story—and it has to be understood for portfolio decisions to be fully informed.

Of all the debates in capital markets today, there probably isn’t one that’s more heated than the roles of active and passive management in the years ahead. But there’s a story within the story—and it has to be understood for portfolio decisions to be fully informed.

THE BACKSTORY: HOW WE GOT HERE

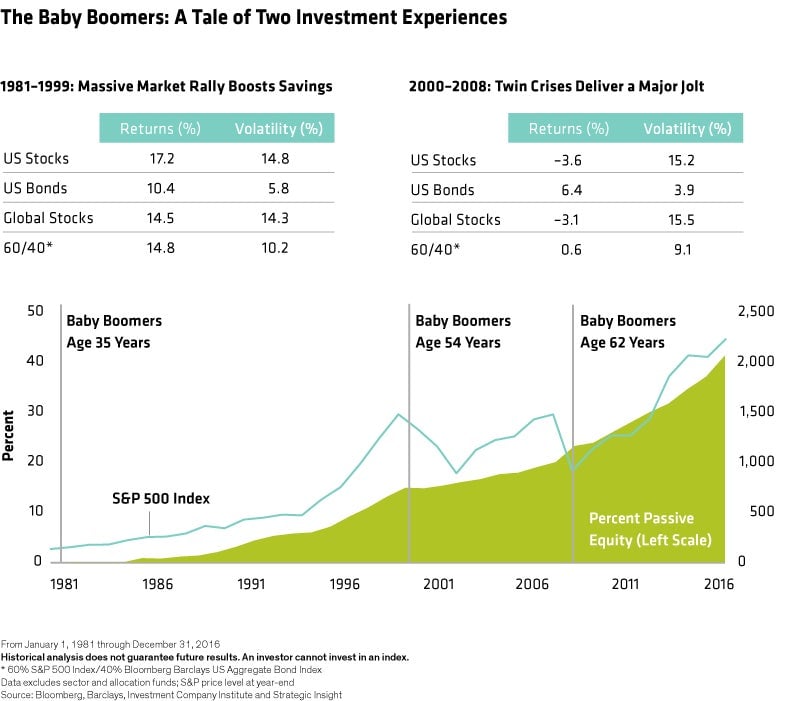

In the early 1980s, baby boomers began to enter their peak earning years. And they were fortunate to step into an environment that would unleash the biggest wind-aided equity bull market in history.

From 1981 through 1999, this massive equity run featured over 17% annualized returns from the S&P 500. It combined with growing wealth among baby boomers to produce a winning formula for investors. But as the oldest boomers began to approach their retirement years, they were hit with two major market crises—the bursting of the tech bubble and the global financial crisis.

This challenging period from 2000 through 2008 left investors reeling. Their wealth was eroding just as they saw retirement approaching. The shock from this reversal of fortune caused many baby boomers to reexamine the way they thought about investing.

One of the prevailing thoughts? “Active management didn’t help me defend in the downturns.”

WHY ACTIVE MANAGEMENT FAILED…AND DIDN’T

It’s true that active managers—as a group—underperformed over time. But it’s also true that the success of active managers varies a lot based on important factors such as the specific time period, the equity category, and how active a manager really is.

We see two structural themes behind active’s slump.

First, both actively managed assets and asset managers’ staff saw explosive growth in the 1990s. That growing number of alpha seekers made it harder to add value by being active. Second, many active managers that had raised large amounts of assets became less active, managing closer to the benchmark—perhaps to avoid underperforming in a strong beta market.

A well-known academic study of a 20-year period from 1990 through 2009 compared the degree of active management with performance versus benchmarks. Active managers, as a group, underperformed their respective benchmarks after fees by about 40 basis points per year.

But when the researchers looked closer, they found that truly active managers actually fared quite well. The most active 20% of managers, who the study called “diversified stock pickers,” outperformed their benchmarks by 126 basis points per year. The takeaway: being more active led to more outperformance.

MARKET ENVIRONMENT MAKES A BIG DIFFERENCE

In the great rising tide of a strong beta-driven market, the individual boats of active management don’t really matter. In periods when equity-market returns were 10% or higher, only one-third or so of active managers outperformed their benchmarks. But when market returns were under 10%, over half of active managers outperformed.

The current environment suggests that the landscape ahead will be more favorable for active managers. Equity valuations are higher than normal today, and market returns are likely to be lower ahead, tax cuts and repatriation notwithstanding. With returns likely to be lower and volatility higher ahead, dispersion among individual stock returns seems likely to rise: when stocks travel increasingly different paths, there are more opportunities for active managers to stand out.

PASSIVE INVESTING ISN’T A PANACEA

On the other side of the ledger, we have passive investing. There’s no doubt that passive investing has brought great benefits to investors, allowing them to access capital markets at a low cost.

However, just as the explosive growth of active investing eventually created structural challenges, so has the surge in passive investing. Today, there are only 768 US stocks with a market capitalization over $5 billion, but there are 1,808 exchange-traded funds (ETFs) chasing them. That’s a lot of vehicles chasing a few stocks—and it’s creating unintentional crowding in specific stocks and market segments.

No one really knows what it means to have so much of the world buying the same stocks based purely on their weightings in an index. And it’s hard to dimension the potential hazards and distortions created by all the overlapping exposures of passive ownership; it could have a large-scale, spiraling effect on stocks that are widely held by passive vehicles.

THE PENDULUM SEEMS TO BE SWINGING TOWARD ACTIVE

Today, the market environment seems to be moving in active management’s favor. Active management has historically been more effective in moderate-to-low-return equity markets—and during market declines. And the high-double-digit equity returns of the last decade, fueled by easy-money policies, are likely a thing of the past.

Volatility, which has been abnormally low for years, is likely to rise—we’ve seen bouts of volatility already in early 2018. When markets are more volatile, individual stock returns show higher dispersion—to put it another way, they increasingly tend to follow different paths. That gives active managers the opportunity to deliver alpha by picking winners—and avoiding losers.

The way we see it, the debate really shouldn’t be about passive versus active. It’s about how and where to deploy each to get the most effective balance. Given the factors that seem to be tilting in favor of active, it seems that investors who give up on active management could be leaving money on the table.

To learn more about responsible investing, visit AB (AllianceBernstein) or read the whitepaper.

This article was produced by AB and not by the Quartz editorial staff.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.