The unintended consequences of a crackdown on sites selling sex work

The internet transformed modern commerce, especially the market for sex. An online marketplace makes it easier for sellers reach more customers, and for those customers to be more informed and discerning thanks to detailed reviews by previous buyers. Economists presume all this information has made the sex trade more efficient, with participants getting better prices and more transparency. The internet expanded the market, boosted pay for sex workers, and improved their safety.

The internet transformed modern commerce, especially the market for sex. An online marketplace makes it easier for sellers reach more customers, and for those customers to be more informed and discerning thanks to detailed reviews by previous buyers. Economists presume all this information has made the sex trade more efficient, with participants getting better prices and more transparency. The internet expanded the market, boosted pay for sex workers, and improved their safety.

The online market for sex is now disappearing after the US Senate passed the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA). Donald Trump signed the combined bill this week. Even before the measures passed into law, their effects were apparent.

The market for sex was one of the first to move online. Before, sex work mostly consisted of street walkers, often controlled by pimps, and higher-end escorts who typically worked with agencies. The middle men were necessary to find and screen clients. Sex workers gave up control of their lives, and their earnings, for regular access to customers and some modicum of safety. One-third of all sex-worker homicides are due to murder by serial killers (pdf). At the same time, pimps were also a regular source of violence.

Starting in the late 1990s, sex workers struck out on their own and advertised on different websites like Craigslist. Soon, specialized websites sprung up to serve different segments of the market: Craigslist personals and Backpage on the lower end, and sites like Eros on the higher end. Providers no longer needed to rely on middle men to find clients because they could advertise directly to them. Sex workers could also screen clients before they met them to ensure they were not violent or police (or both). Sex workers developed a referral network, including message boards to warn each other about dangerous clients. They were able to verify customer identity by calling their employers and asking for forms of ID.

Meanwhile, customers reduced their risk by posting detailed reviews on sites like the Erotic Review. This mutual screening made sex worker safer. Baylor economist Scott Cunningham’s research (pdf) found that Craigslist’s erotic services pages led to a 1-17% reduction in homicides, and a modest decline in rape.

More money, independence, and safety attracted more sex workers into the market. Yet even as supply and transparency increased, the price for sex also increased. This is because more high-end escorts entered the market, and escorts use the websites to compare pricing information.

The sites were able to host ads for illegal sex work because Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act does not hold them accountable for the free speech of their users. The new legislation, however, amends Section 230 so sites can be prosecuted if they engage in the “promotion or facilitation of prostitution” or “facilitate traffickers in advertising the sale of unlawful sex acts with sex trafficking victims.”

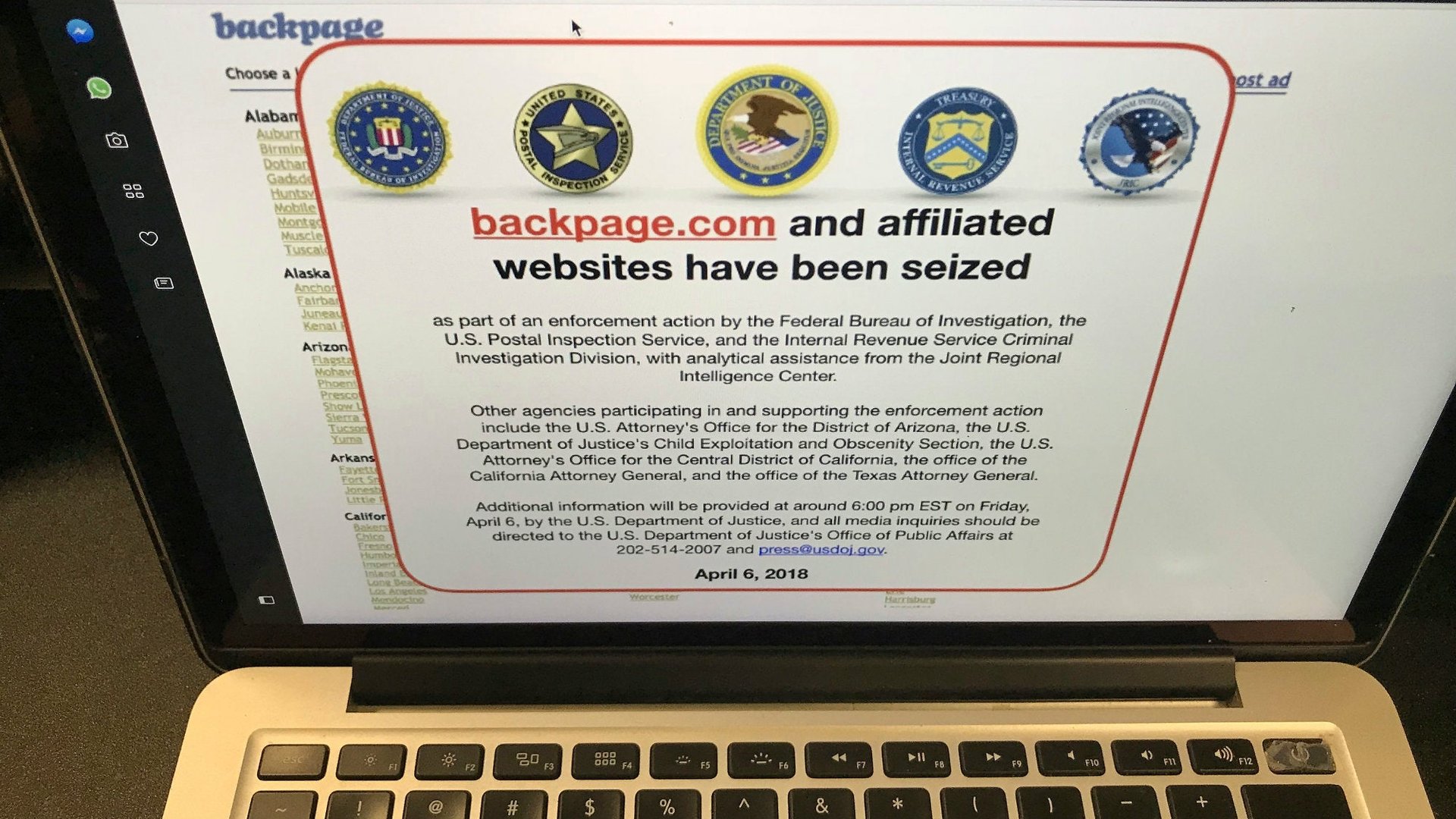

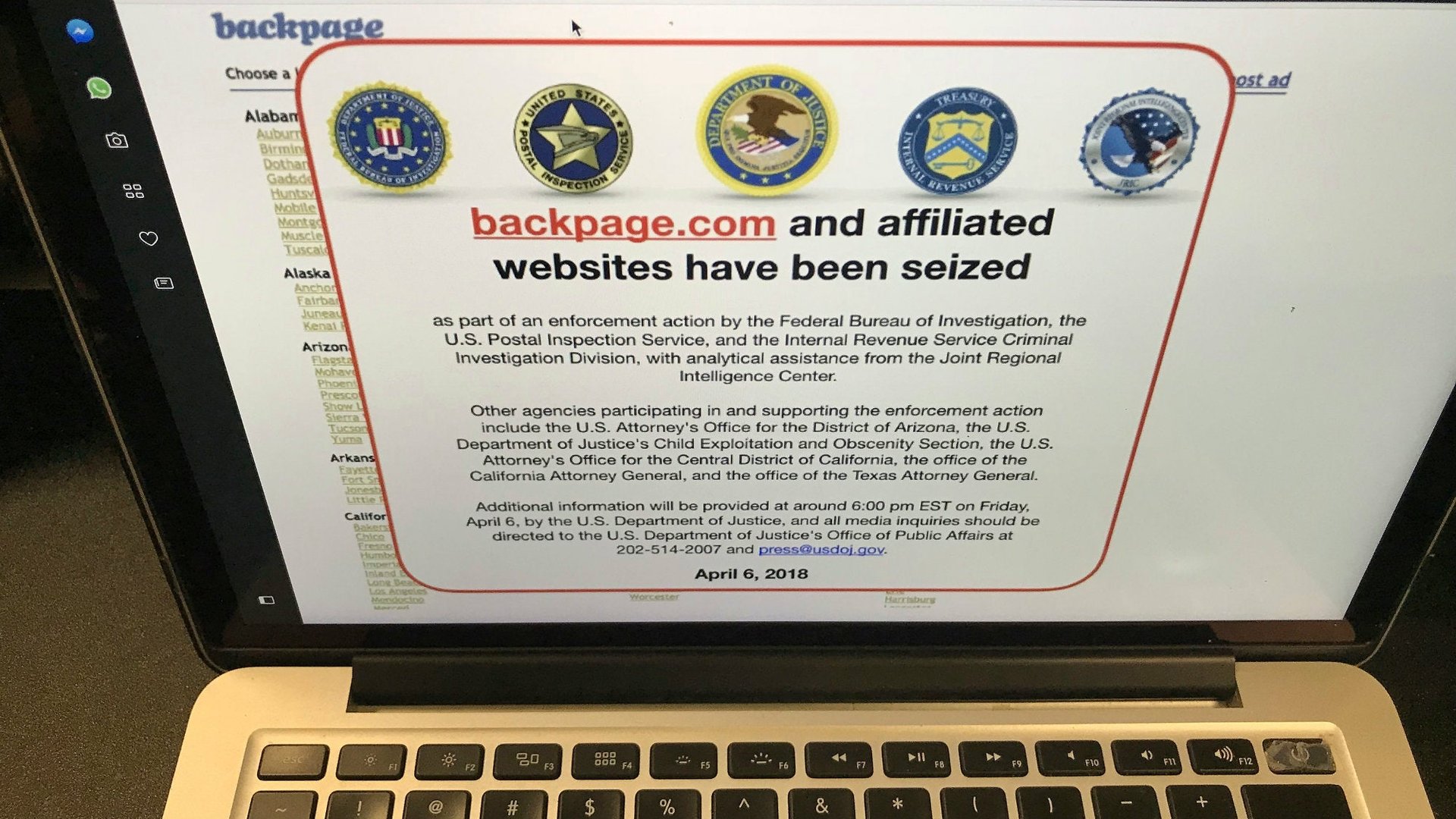

The purpose of the bill was to reduce sex trafficking following a two-year Senate investigation into Backpage. The investigation found BackPage knowingly aided sex trafficking of women and girls. Last week, the Justice Department announced seven people were indicted on 93 counts related to facilitating prostitution and money laundering. The indictment highlighted several incidents of knowingly advertising minors on the site.

Sex-trafficking is small share of the market, and not all websites are Backpage. The language of the law targets any website that advertises sex, even between consenting adults. In response to the new law, The Erotic Review shut down its US website, Craigslist Personals is no more, Backpage is gone, and the future of similar sites remains uncertain.

The new law will probably shrink the size of the sex market, but will not eliminate it. No matter how most people feel about sex work, the market for it will never go away. For willing sex workers, the new rules remove a community that helped make their work safer. Glenn Spence, a female sex worker, told New York Magazine:

What I’m really concerned about is the loss of screening information and the loss of community blacklists is going to mean. I have enough shaky social capital and have enough latitude that I can say, “Give me some employment verification,” whereas, most workers who are even a degree or two below me on that hierarchy can’t afford to spook clients by asking those questions. The only thing they can rely on is shared community information.

The new law may not even help victims of trafficking. Sites like Eros verified the identities of sex workers to confirm they were willing adults. Many sites claim they work with law enforcement to identify victims of trafficking. This may come back to haunt Eros users. How the law will be enforced remains unclear, but it is possible it can be applied retroactively to people who used the sites years before the law was changed.

One thing that is certain is shutting down web sites moves trafficking further into the shadows. After Backpage shut down its adult ads section last year, the New York Times reported more sex work moved to the the street, sex workers were more reliant on pimps, and law enforcement had a harder time finding victims.