Duolingo’s crowdsourced language-learning model is letting some weird things slip through the cracks

Duolingo has pulled off a remarkable feat. The startup, valued at $700 million, has built one of the world’s most popular language learning apps while only hiring a handful of translators. Each day, the startup serves up millions of sentences, almost all of them created by its 300 or so volunteers.

Duolingo has pulled off a remarkable feat. The startup, valued at $700 million, has built one of the world’s most popular language learning apps while only hiring a handful of translators. Each day, the startup serves up millions of sentences, almost all of them created by its 300 or so volunteers.

The seven-year-old company achieved this trick by repeating what its co-founder, Carnegie Mellon computer scientist Luis von Ahn, has accomplished twice before: turning the online crowd into the basis of the business model. In 2003, he launched “ESP Game,” crowdsourced image labeling to improve visual search, which Google licensed and rechristened Google Image Labeler in 2006. Three years later, Google was back again to buy von Ahn’s bot-detecting creation CAPTCHA, deploying it as reCAPTCHA, with humans deciphering text to help digitize books.

With Duolingo, von Ahn has refined the model to tackle one of the most sophisticated tasks on the web: accurate, nuanced translations of foreign languages. While algorithms have offered rough approximations for years (see Google Translate), humans are still needed to achieve translations precise enough for avid language learners. Crowdsourcing has proven to be the key. Without volunteers, Duolingo says its mission to make “language learning free and accessible for everyone in the world” would likely be impossible.

Today, Duolingo serves up courses via its app as well as through browsers in 31 languages to 200 million users (25 million are active monthly users). After its latest fundraising round last summer, the company’s venture war chest topped $108 million with investors such as Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers, Union Square Ventures, NEA, and Drive Capital, as well as Ashton Kutcher and Tim Ferriss.

Duolingo needs that backing: It’s competing against more than 600 other companies, according to AngelList, ranging from incumbents such as Rosetta Stone to upstarts like Verbling, Colingo, Mermrise and FluentU (but few have the venture capital or the valuation as Duolingo). Business models abound: some play annotated Youtube videos (FluentU) and others connect you with real people around the world (Colingo’s “Airbnb for English-teaching”). Some rely on subscribers, and others on advertising.

von Ahn claims crowdsourcing was never in Duolingo’s original business model. Companies were supposed to pay for translation services from algorithmically-aided language learners who would help “translate the web.” The company’s material came from blog posts, Wikipedia entries, commercials, news articles and other free content. After 2015, this model was dropped as the company turned its ambitions to serving a global audience of language learners. But staffers’ early attempts to write language courses were too slow and expensive to scale. The company realized the only way it could serve such a massive audience was generating content for free. Duolingo’s volunteers heeded the call.

Language learning: crowdsourcing’s biggest challenge

At the heart of Duolingo are its engineers, some of whom reportedly pitch in on language duties. Of the 100 or so employees, more than half work in engineering while just three people manage the volunteer community. Overall, only 6% of the company works on “product” and “research” (although a few language experts also consult with the company).

Duolingo makes this structure work by appointing volunteer contributors and moderators, who apply through its website, to oversee course creation and discussion forums in each language. The company says volunteers are vetted for language skills, and then trained on subjects from pedagogy to guidance dealing with gender, diversity, and cultural sensitivity issues.

Some are hobbyists, while others are language professionals (Duolingo calls them Global Ambassadors). For course creation, a person may oversee a team of three to 10 volunteers. Volunteers work at their own pace, but the company has said a single course can take a full-time volunteer about four months to complete. Full courses can encompass 400 lessons with more than 2,000 words and 10,000 to 20,000 sentence examples.

This work is fed into the core of Duolingo’s language service, “The Incubator.” This language database allows hundreds of volunteers to write and translate thousands of phrases and sentences. Teams revise the language, sometimes with input from staff or consultants. “Beta courses” are then offered to users who want to polish new courses, and finally released into the wild. An algorithm pulls from this pre-approved content, as well as images of speakers, to create interactive cards, with users’ courses personalized based on their past performance.

Duolingo calls this model a win-win for its volunteers and learners. Volunteers’ work looks “great on your curriculum vitae and social profiles,” the company states, while the company can “publish, build upon, or otherwise invest in your awesome idea” because volunteers’ work falls under a Creative Commons license. Although Duolingo has staff and consultants on payroll, it doesn’t pay for most of its language content.

Duolingo’s monetization plan will get the company to break-even in 2019, wrote Duolingo spokesman Sam Dalsimer in an email. With the company’s original translation services off the table, the company is focused entirely on growing its user base. Last year, it introduced ads into its free service and a paid subscription product with downloadable lessons. It also charges for English certification tests. The company would not release any revenue numbers.

But does it work? Duolingo points to a study it funded in 2012 (pdf) claiming someone with no knowledge of Spanish can cover a college semester of the language in 34 hours on average. Beginners gained the most, the study found, while more advanced speakers’ proficiency advanced the least. There was no long-term follow up on retention and fluency.

Melissa Baese-Berk, an associate linguistics professor at the University of Oregon, says language researchers haven’t fully investigated apps like Duolingo yet, but she sees a lot of benefit to them because, unlike textbooks, “they get people excited about language.” For those looking for advanced study, however, “the quick and easy way may not be the most efficient way,” she said. “If you expected to become fluent after using Duolingo, it’s not within [its] skill set at this time.”

Getting the words right

Screening millions of sentences per day is only possible because Duolingo relies on algorithms and its own users to monitor content. Dalsimer says the company ultimately takes responsibility for the content and training volunteers, with guidance on LGBTQ, diversity, inclusion, and cultural sensitivity. The program gives volunteers a restricted set of words and orders in which they can be used. Algorithms improve content based on user feedback. In cases where there’s a problem, staffers can step in to resolve it.

Duolingo’s standards prohibit pornographic, bullying, racist, excessively profane or violent language, as well as spam and personal, confidential information. “It’s extremely rare; about one out of every 1,000,000 user reports leads to a removal of content due to a violation of our content policy,” writes Dalsimer.

To flag such content, Duolingo relies on a “report” button in the app to flag content that might make it past its moderators and beta testers. Staff may “work closely with the volunteers” to launch new courses, writes Dalsimer, but not all content that makes it into the wild cannot be fully reviewed by staff due to the size of its user base.

Given the automated nature of the courses, much of Duolingo’s content is playful or nonsensical as the algorithm pulls character images and sentence phrases from its database at random. “I am a horse. I speak English” may be uttered by a bear or zombie. Or a female might say “Yes they are real,” in which case it’s as likely to have an innocent intent as much a sexual meaning given the range of interpretations, claims Duolingo.

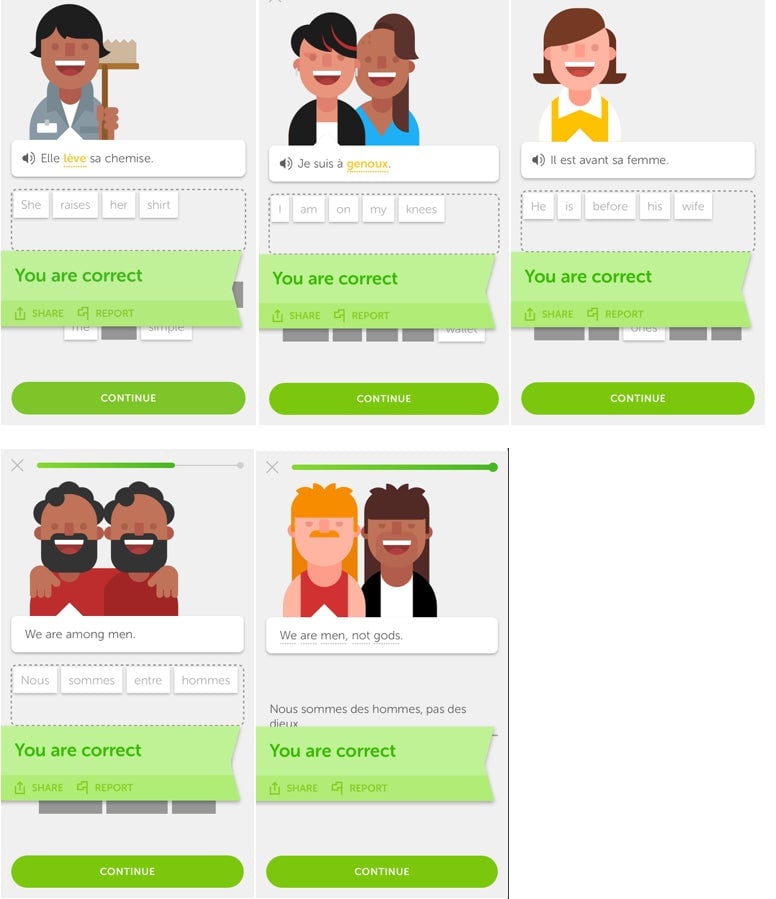

But Duolingo does remove content, and has yanked problematic content in the past. Content from the French course viewed by Quartz is one example. “She raises her shirt” and “I am on my knees” were both part of a course provided to one user. After being contacted by Quartz, Duolingo said it had removed first example “because it violates our content policy,” and the second for its suggestive pairing with female character illustrations. A third, “He is before his wife,” illustrating the French word avant meaning “before” had multiple interpretations and was retained.

Users on Duolingo’s discussion boards were vocal in their defense of the company. When asked about inappropriate or sexual content, posters on its message boards insisted “that stuff doesn’t even exist on this site,” and suggested the problem lay more with “dirty-minded” users rather than the content itself.

Baese-Berk at the University of Oregon says that crowdsourcing content is a potential boon to language learners. Although she was unaware Duolingo’s content primarily came from volunteers, Baese-Berk admitted the quality woudn’t necessarily suffer since even experts don’t have a perfect grasp on the best ways to convey the nuances of foreign languages to non-native speakers. “Everyone is really an expert in [your own] language whether you know it or not,” she says. “What linguists are trying to figure out is how we are experts about language.” Duolingo’s failings may be outweighed by its ability to get people motivated to learn. But if you’re serious, you’ll need to ditch the app, and buy that plane ticket. “The most effective way of learning a language is immersion,” she says.