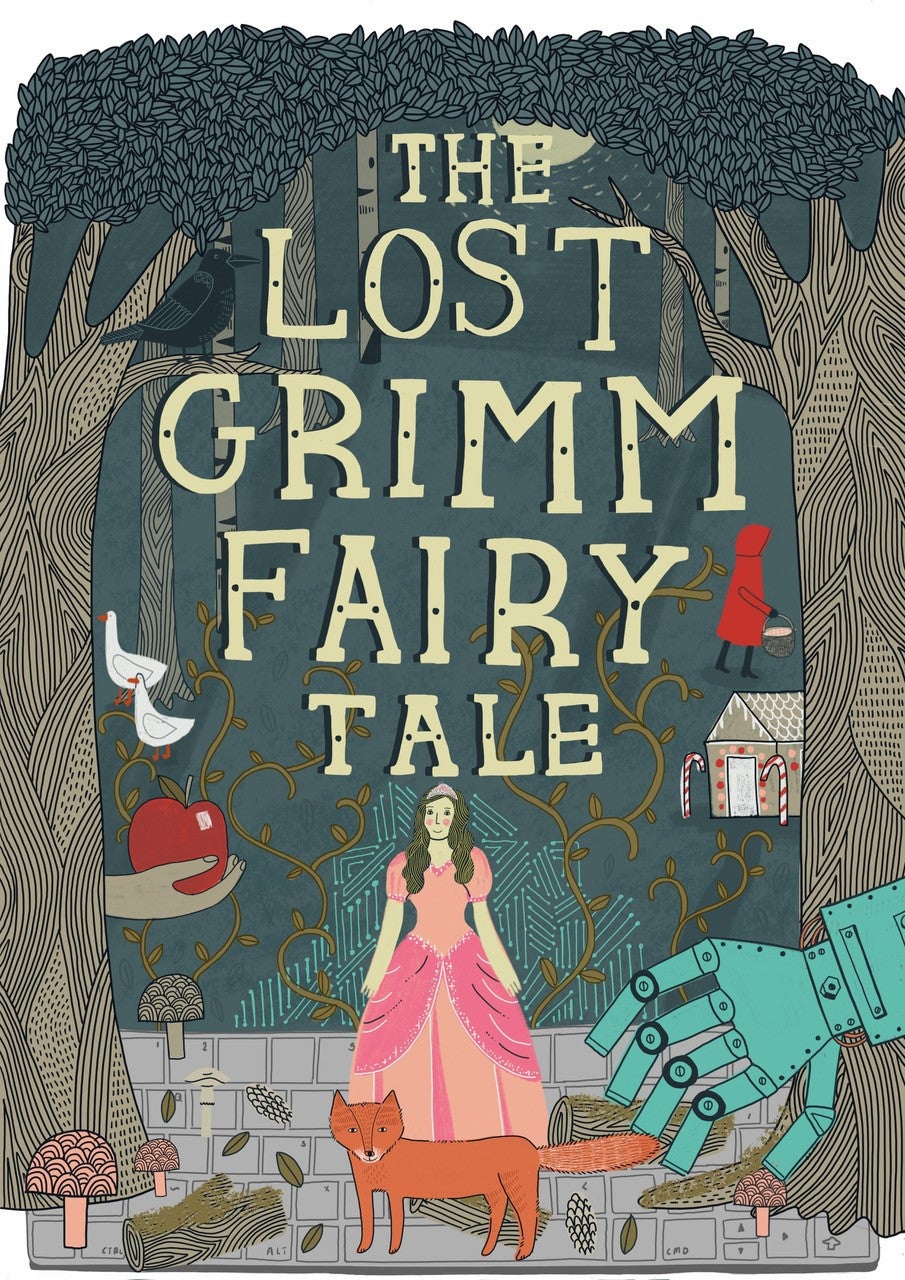

AI learned to mimic Brothers Grimm fairytales—including their sexist stereotypes

The Grimm brothers’ seminal book of fairytales is over two centuries old. But the duo has been credited with a new story, “The Princess and the Fox,” just this month—with some help from artificial intelligence.

The Grimm brothers’ seminal book of fairytales is over two centuries old. But the duo has been credited with a new story, “The Princess and the Fox,” just this month—with some help from artificial intelligence.

Released by the meditation app Calm, ”The Princess and the Fox“ was written by Botnik, a company that uses machine learning and predictive algorithms to write text. The story was released on the app on April 11, and is available in audio form.

This is not necessarily new: AI-generated fairytales have been around for a long while now, with the first dating all the way back to the 1930s, as Mark Riedl, a professor of artificial intelligence at Georgia Tech, writes in his history of AI-generated stories. And programs that mimic the Grimm brothers’ language have also been done before, according to Isaac Karth, an AI researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Regardless, what makes “The Princess and the Fox” stand out is it does a great job mimicking the style and patterns of the Grimm stories and other folk tales. And that means the story mimics some hoary gender tropes, too.

An artistic collaboration between AI and humans

“The Princess and the Fox” isn’t written entirely by AI. Rather, it’s an experiment in collaboration between humans and machines, according to Jamie Brew, Botnik’s CEO.

The text, Brew explains, was generated through two predictive text keyboards. A narrative keyboard built the general structure of the tale, while a dialogue keyboard reproduced Grimm-like exchanges. Humans pick and choose from the AI-generated possibilities. “The human writer gets a range of suggestions at each step of the sentence,” explains Brew. The suggestions, he explains “appear because the algorithm assigns them some likelihood based on word patterns in the source text.”

Botnik has used a similar approach with other works, from Radiohead songs to Harry Potter and poetry. “However you slice it,” Brew says, “human participation is intrinsic to our writing process, and we wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Princesses are always beautiful

The resulting text, “The Princess and the Fox,” is the “tale of a king, a magical golden horse, a forlorn princess, and a poor miller’s son,” according to Calm’s description. “A talking fox helps the lowly miller’s son to rescue the beautiful princess from the fate of having to marry a dreadful prince who she does not love.”

The story includes some odd transitions and slight logical incoherency. But the tale is very much Grimm-like, and its incongruences add a bit of surreal charm to the whole exercise. (No doubt René Magritte and his pals would have very much liked to play with Botnik’s keyboards.)

Because this is a traditional story, it replicates the stereotypes found in many fairytales—particularly the idea that the ultimate life goal for a worthy damsel is to be chosen, and saved by, a dashing prince.

The story begins (bold text ours):

Once upon a time there was a golden horse with a golden saddle and a beautiful purple flower in its hair. The horse would carry the flower to the village where the princess danced for joy at the thought of looking so beautiful and good. “It’s magnificent,” she said to her father, the King of Bread and Cheese.

Here we have a princess whose self-worth hinges so much on her appearance that she has a whole interpretive dance about wanting to look more like the gold horse who visits her village sometimes. Throughout the rest of the story, the text constantly reminds the reader that the princess is kind, good, joyous, and, most importantly, beautiful. While she does, at one point, refuse to act according to her father’s wishes, it is the only mark of rebellion in a character whose actions otherwise seem limited to dancing, smiling, or crying. That’s enviable compared to her mother, the only other woman in the story: The queen mostly nods. The rest of the action is up to the five male characters: two princes (one in disguise), a king, a fox, and that good-looking horse.

A matter of bias

“AI corpus-trained systems pick up the biases of their corpus data,” says Kate Compton, an AI researcher at UCSC, “and that is a big problem.” However, humans were involved in creating “The Princess and the Fox” too, so the story’s bias can’t simply be blamed on the machine. In this case, says Compton, part of the bias comes from “all of the cultural training of the writers that went into selecting an idea and turning it into a story.”

Interestingly, the story’s replication of traditional gender tropes was in fact a desired result. “On the first pass, I think our writers mostly gravitated toward weird and surprising images,” Brew says. And so the first version of the story actually had a miller’s daughter save several princesses. But these elements, as well as a few absurd details, were edited to focus on maintaining the Grimm voice and aesthetic, per Calm’s input.

The issue is not unique to this particular story. “Any system that you train off of human-produced data will have the potential of picking up on human bias,” says Riedl. But, he also notes, “we often think of biases as bad, but it’s important to remember that all data and all stories have bias—without any bias we don’t have any stories.”

Riedl suggests that our goal with AI-based narratives should not necessarily be eliminating all biases, but deciding how, and whether, to update the AI’s frame of reference so that the story it produces is in keeping with current values. ”Our biases, tropes, and stereotypes do change over time, and we can’t necessarily apply our bias back in time,” he says.

Researchers like those in the Botnik collective are thus a new breed of cultural gatekeepers: They must decide whether to preserve a certain aspect of culture (such as the Grimm aesthetic) or get rid of stereotypes and patterns that are no longer relevant, or are outright offensive. “It’s a double-edged sword,” Riedl says—but in the right storytellers’ hands, that sword could still be a magical one.