President Buhari’s slips, Nigeria’s “lazy” youth and a looming education crisis

I regret to inform you that president Buhari has done it again. Just over two years ago, I had cause to defend the constituency of which I am a part when he made remarks in London during a newspaper interview implying that Nigerians abroad have a single story of criminality. A few days ago during a Commonwealth Business Forum session, in London yet again (what is it about London that triggers the president one wonders), he made comments that kicked up an almighty firestorm among young Nigerians. His supporters will try to say it was a slip, but it’s a slip he keeps making.

I regret to inform you that president Buhari has done it again. Just over two years ago, I had cause to defend the constituency of which I am a part when he made remarks in London during a newspaper interview implying that Nigerians abroad have a single story of criminality. A few days ago during a Commonwealth Business Forum session, in London yet again (what is it about London that triggers the president one wonders), he made comments that kicked up an almighty firestorm among young Nigerians. His supporters will try to say it was a slip, but it’s a slip he keeps making.

In answering, or trying to answer, questions about Nigeria’s troubled north east, the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA)—which Nigeria pulled out of signing at the last minute—and Nigeria’s economy in general, he delivered a broadside at Nigeria’s young population saying they were lazy and entitled and perhaps deluded.

More than 60% of the population is below 30, a lot of them haven’t been to school and they are claiming that Nigeria is an oil producing country, therefore, they should sit and do nothing, and get housing, healthcare, education free.

What was most amusing, for lack of a better word, was not whether young Nigerians are deluded. It was the idea that a Nigerian government has any of the above gifts in its power to dispense.

It is the president’s comments about education that are most painful and downright cruel. It is impossible to exaggerate the damage that has been done to Nigerian education over many years. Routinely, at every stage, it fails young Nigerians and then delivers them into the job market with no skills or preparation to take on the world and make a success of their lives. And they are the lucky ones—UNICEF estimates that Nigeria has 10.5 million children of school age who do not get into school at all, the highest in the world.

Following the journey of children through the Nigerian education system, and the federal funding that follows them, is a traumatic exercise. At the primary school level (the responsibility of cash-strapped and hapless state governments) and secondary levels (where the federal government steps in with a relatively minor role), funding for education is terribly squeezed or even non-existent. Though many millions will drop off along the way, for the students who manage to make it to higher education the federal government then turns on the funding tap.

In the proposed 2018 budget (pdf, pg 1228) the federal government proposes to spend a total of 606 billion naira ($1.7 billion) on education. About 400 billion naira of this total (65%) goes directly to higher education. The federal government’s contribution to basic education gets 114 billion naira (96% of which goes to salaries) via the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC). The over 100 secondary schools the federal government is responsible for, collectively known as ‘unity schools’, get a total of 32 billion naira to share among themselves, 8% of what goes to universities.

How Nigeria came to neglect and debase primary and secondary education and then dedicate the biggest chunk of its budget to tertiary education has many reasons but two in particular stand out.

First, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) is easily one of the most effective unions in Nigeria in terms of getting the government to bend to its will. It is impossible to write Nigeria’s history since 1978 when the union was formed without documenting the numerous strikes they have embarked on. As a victim of Nigerian universities myself, one year was added to my university education by ASUU strikes and I can be considered lucky, many others had more than a year added.

These strikes and ASUU’s relationship with the government are almost comical to observe. They demand money, government ignores them, they go on strike, the government agrees to their (impossible) demands, they go back to work. Everyone breathes a sigh of relief waiting for the inevitable accusations from ASUU that the government has reneged on its agreement. Most recently it claimed the government owes universities 800 billion naira, more than double what they are to receive in this year’s budget. At some point in the near future they will go on strike again and the government will pay up in some form.

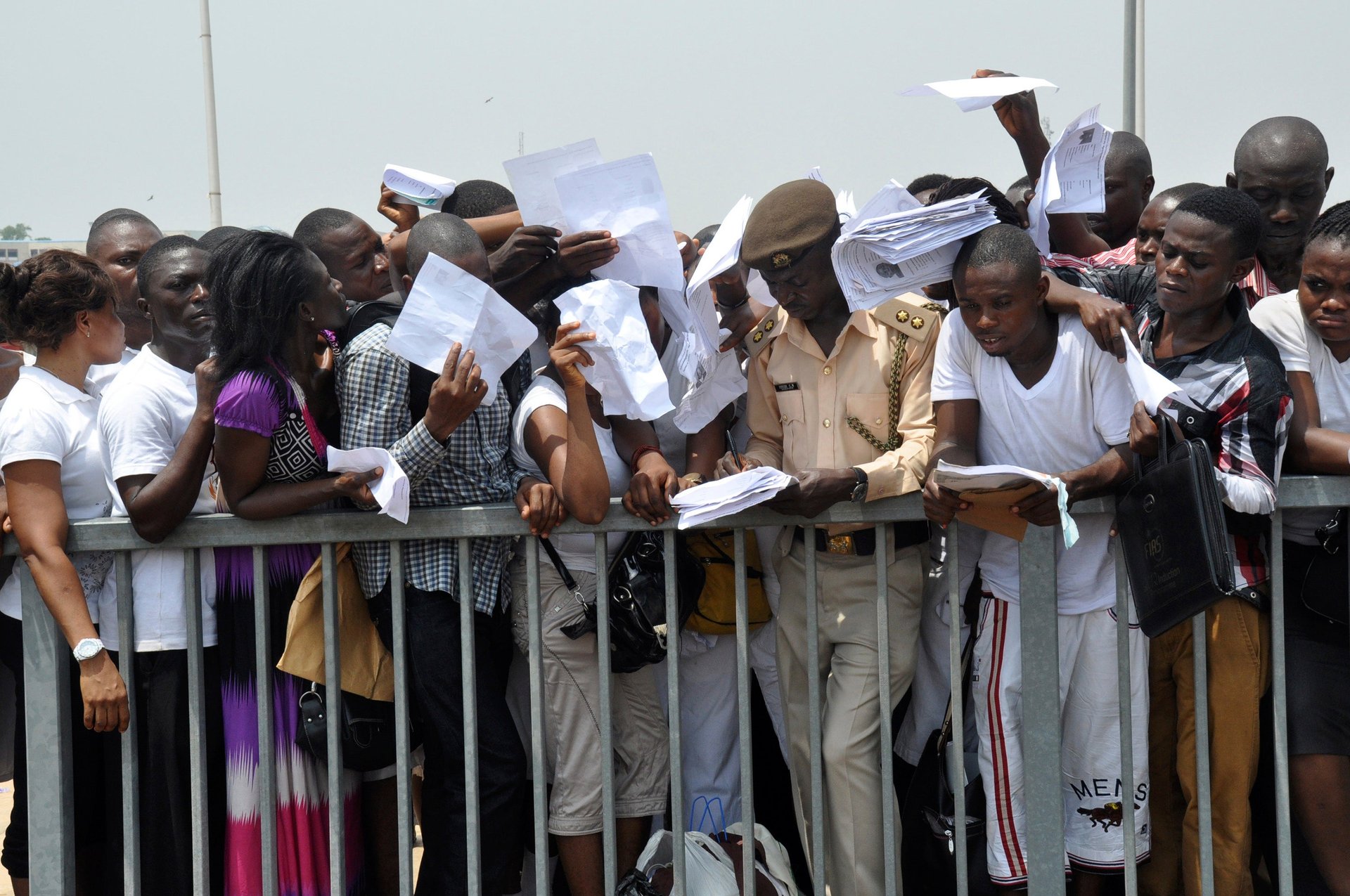

The second reason explains why ASUU’s strikes are so effective. As a result of the government absconding from the lower levels of education, more children are being educated privately at primary and secondary levels than in the public school system. A 2014 report by the World Bank (pdf, pg 9) showed that registered and unregistered private schools accounted for 75% of all school enrollment in Lagos state, the country’s most populous. A few days ago, the junior education minister disclosed that just 80,000 students wrote the entrance exams to get into one of the government’s unity schools. It is a sad testament to how far they have fallen that parents, who can afford better private schools for their wards, no longer bother to get them into what were once considered elite institutions. Nevertheless, over 1.7 million students wrote the university entrance exams last year, competing for around 500,000 university spaces.

Tying these two reasons together, a simple power dynamic emerges. The Nigerian middle class and the politically powerful elite who can cause the government a great deal of discomfort have long abandoned public education at the primary and secondary levels. Were primary and secondary teaching unions to go on strike demanding more money like ASUU, they might not make the news at all. But public universities continue to educate the vast majority of higher education students in the country. For the rich and powerful, the other options are the handful of private universities or sending their kids abroad (like president Buhari does). Both options are currently exercised by a minority of people, albeit a growing one. Thus, any hostage taking via strikes is very effective at getting the government to capitulate.

This power dynamic is best illustrated with the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND). In 1993, a decree, by the then military government, established the Education Tax Fund (ETF) which mandated a 2% tax on the profits of all companies in Nigeria. The fund was to help supplement government funding for all levels of education in Nigeria. Half of the ETF went to primary (30%) and secondary (20%) with universities getting 25%. Polytechnics and colleges of education got 12.5% each. But in 2011, ASUU successfully lobbied and forced the government to change the law which transformed the ETF into TETFUND. Today, the 2 % tax on companies only funds higher education with universities getting 50% and polytechnics and colleges of education getting 25% each. Primary and secondary education has been kicked out of it.

University lecturers in particular have since turned TETFUND into another source of funding for themselves. They now apply to the fund for grants to study abroad for masters and PhD programs (while they continue to earn their full pay). An official report by TETFUND for September 2017 showed that it approved funding for a total of 449 masters and PhDs in that month alone 106 of them outside Nigeria. It also approved 283 conference attendances for that month, 66 of them abroad. The most recent available audit of TETFUND in 2013 showed that it received 366 billion naira between 2007 and 2011, the last year before it was exclusively taken over by higher education. The report shows that a significant chunk of the money was going to state primary education boards where Nigeria’s education system is currently failing the most.

If young Nigerians “haven’t been to school” as the president said, it is no accident—it is the outcome of a system designed to do just that. Over many decades, the government has abdicated its most basic responsibility to set up children with a basic education at primary and secondary levels. Only by the time it is far too late does it then respond to hostage takers by handing over the chunk of its budget to them.

President Buhari has not shown even the slightest sign that he has thought about these problems let alone proffer solutions to them. He appointed a most disinterested minister of education who was hardly seen nor heard for the first two years of his government. There is no sign that the government recognizes that the nation is in the grip of an education crisis at all levels. It simply carries on as normal and, as the president even said at the Commonwealth Business Forum, it thinks it deserves some accolades for some imaginary achievements it has had.