In Sri Lanka, Facebook is like the ministry of truth

Facebook now reaches 2.2 billion people on the planet. The most lucrative of those are in the US, where its user base is stagnating. To grow, the social media giant will have to expand in less developed parts of the world. Places like Sri Lanka.

Facebook now reaches 2.2 billion people on the planet. The most lucrative of those are in the US, where its user base is stagnating. To grow, the social media giant will have to expand in less developed parts of the world. Places like Sri Lanka.

An investigation by the New York Times (paywall) exposes the costs of that expansion. Facebook has replaced traditional media as a source of news in Sri Lanka, with the content itself created by people who use the platform, not by Facebook, which bears little or no responsibility for what gets published on the site. Times reporters spent months tracking real life violence linked to misinformation and found, in many cases, it led directly back to hate speech on Facebook.

According to the Times:

Time and again, communal hatreds overrun the newsfeed — the primary portal for news and information for many users — unchecked as local media are displaced by Facebook and governments find themselves with little leverage over the company. Some users, energized by hate speech and misinformation, plot real-world attacks.

Rumors of a Muslim plot to sterilize Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority led to real-life violence in February that resulted in the beating of a Muslim restaurant worker. He was falsely accused of spiking the shop’s food with sterilization pills in the small town of Ampara.

Because of rumors on Facebook, a lump of flour found in the food was transformed in the mind of the patron into a sterilization pill. Language barriers between the Muslim operators and the Sinhalese patron made it impossible to correct the falsity and a mob at the restaurant formed that beat the worker, destroyed the shop, and set fire to a local mosque.

A mobile-phone video of the incident got posted on a Facebook group called the Buddhist Information Center. It spread, stoking violence toward Muslims across the country that resulted in more than one death. Mobs in several towns burned mosques, shops and homes owned by Muslims, the Times reported.

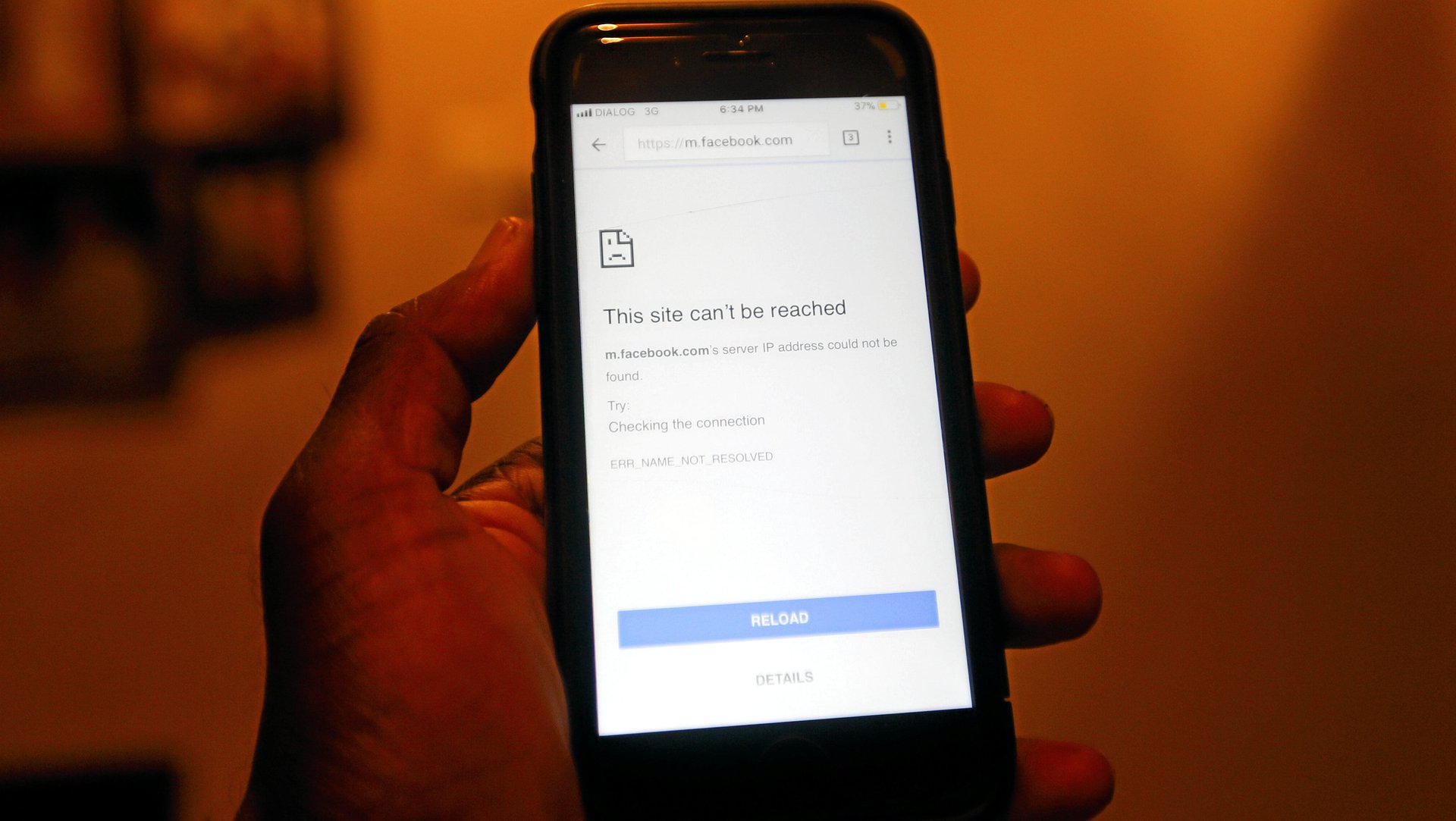

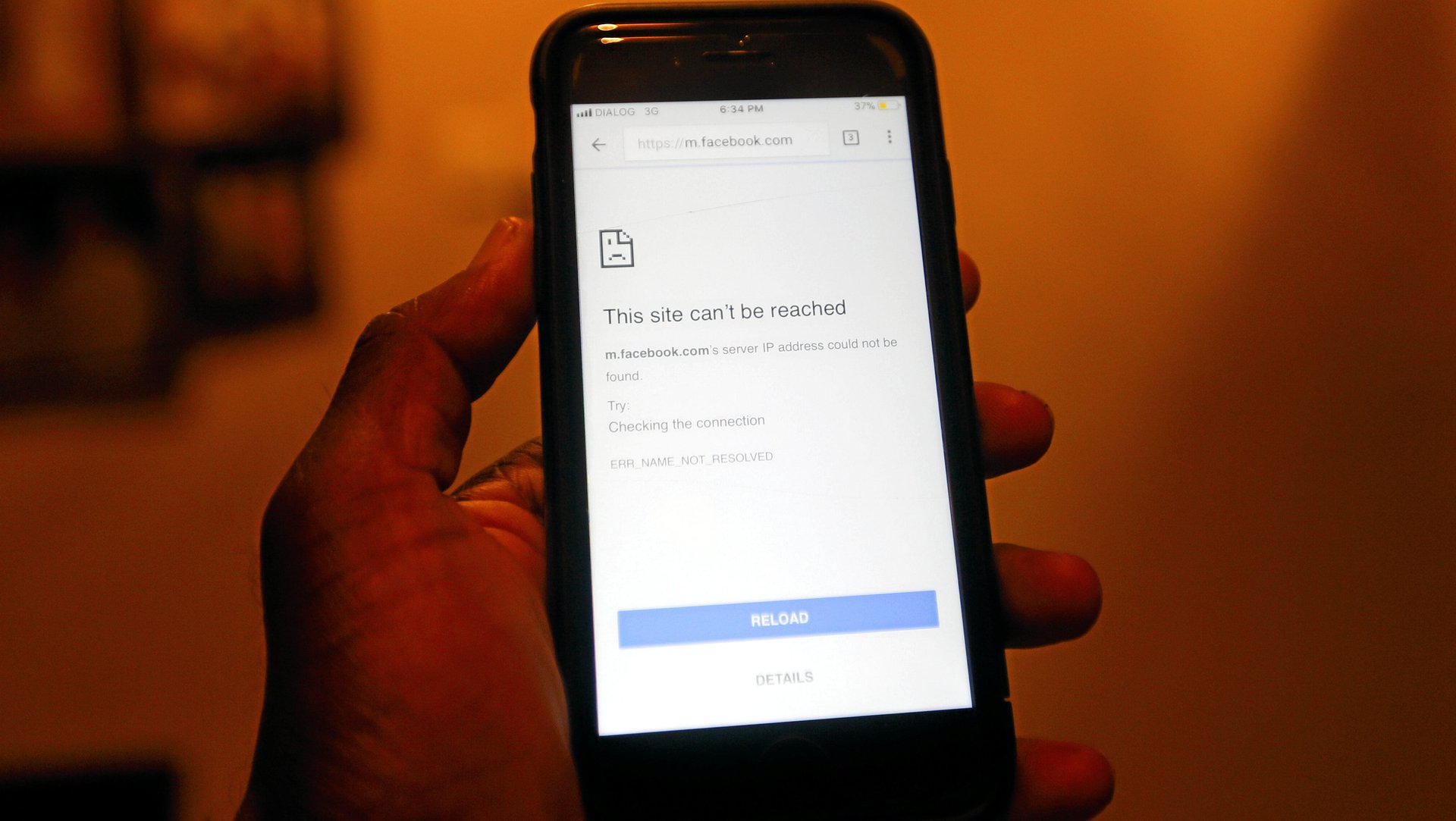

In March, the government of Sri Lanka shut down Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Viber in an attempt to quell ethnic strife in the country. But the issue of Facebook’s role remains.

The social-media company isn’t quite like the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which works to change, correct, and falsify news and information to keep Big Brother in power. Facebook does not manipulate and edit the content on its site. It just provides a platform for distribution.

But that vast power has governments throughout the world questioning how social media is shaping opinions and behavior, raising questions of censorship, free speech, and technology’s ability to shape and form modern society.