Cities are short on housing. That’s bad news for the climate.

Over the last decade or so, white-collar workers have flocked to cities, driving up rents and triggering shortages of affordable housing. Now, advocates and policymakers are in a pitched battle over what to do.

Over the last decade or so, white-collar workers have flocked to cities, driving up rents and triggering shortages of affordable housing. Now, advocates and policymakers are in a pitched battle over what to do.

That conflict came to a head in Sacramento last week, as California legislators killed a bill that would have allowed developers to build high-rise apartment buildings near train stations and bus lines, regardless of local zoning laws. Supporters hailed the measure for cutting red tape. Critics said it would do too little to bolster affordable housing. The bill is dead—for now—but both sides will continue to spar over the future of housing policy.

This is an important fight, because housing policy is about more than just bloated rents. The dearth of affordable homes is also making it harder to guard against air pollution and climate change. Sky-high prices are forcing families to live farther from work in neighborhoods that are heavily polluted or prone to flooding, making it all the more urgent that policymakers find a solution.

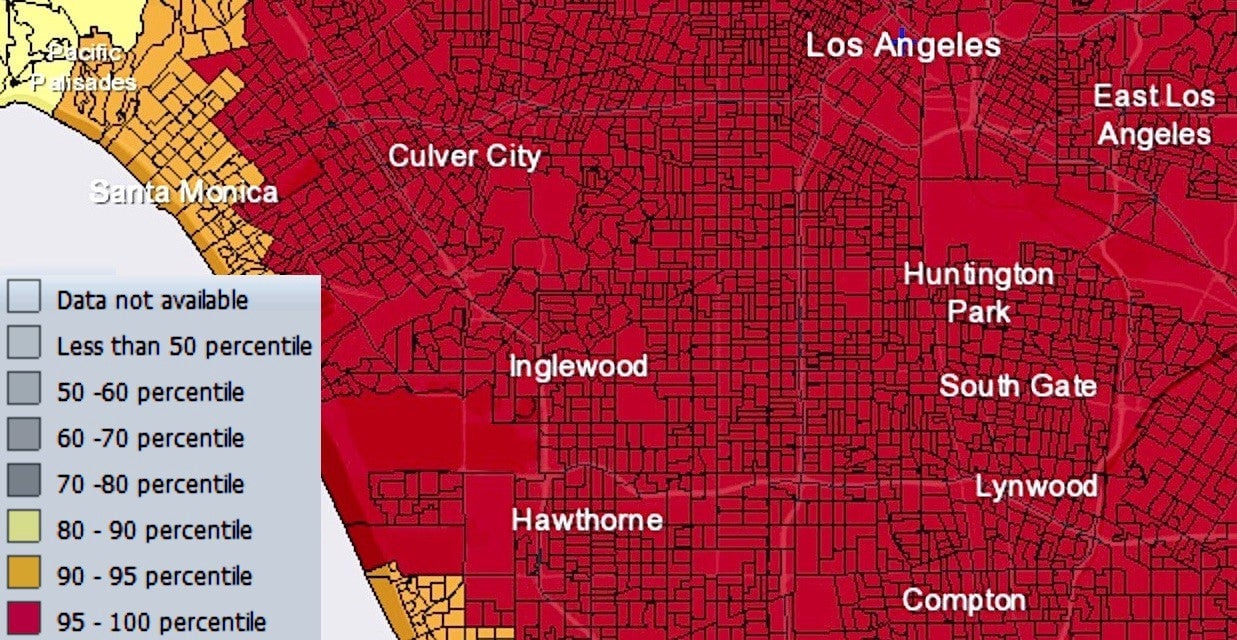

“The nicer areas tend to be developed for more affluent communities, which are comprised of mostly white, rich individuals. Exclusionary policies have pushed lower-income communities—which are largely communities of color—into areas that have issues with air quality, soil pollution, water pollution,” said Ethan Guy, senior manager at Street Level Advisors, a consulting firm focused on equitable urban development. “Those areas are also the most prone to feeling the effects of climate change.”

In large cities, for example, working-class neighborhoods are often vulnerable to rising seas, both because they sit in low-lying areas and because they lack the infrastructure needed to keep floodwaters at bay. That was evident in New York City during Hurricane Sandy and in Houston during Hurricane Harvey. Sea-level rise made flooding markedly worse during both storms.

Flooding isn’t the only problem. Affordable housing also tends to be far from work. A family might save money on rent by moving away from the city, but mom and dad will spend more time driving to work and more money paying for gas, generating more pollution along the way. Working-class families living in cities spend around 60% of their income on housing and transportation, partly a consequence of living far from work.

“A lot of families are being driven further and further away from their areas of employment,” said Chris Durazo, co-director of housing, land and development at Causa Justa, a San Francisco Bay Area housing advocacy group. “People are moving close to the Central Valley and commuting well over two or three hours to work. It’s because there are a lot more jobs in the San Francisco, San Jose and Sacramento areas.”

In city centers, the only affordable homes are often those near highways, factories or power plants, meaning parents and kids put up with more pollution and, as result, more asthma, bronchitis and other maladies. Mom and dad might save on their mortgage, but they pay for it in visits to the emergency room, missed days of school or missed days of work.

While city dwellers everywhere agree the housing shortage is a crisis, no one can agree on the solution. “I think a market-driven solution is probably the best approach,” said writer Nikolai Fedak, arguing that developers could meet the need for more housing if they were unencumbered by onerous zoning policies.

Fedak is the founder of NY YIMBY, an online publication reporting on new real estate development in New York. The title is an abbreviation of “Yes In My Backyard,” a play on NIMBY, an abbreviation of “Not In My Backyard,” an epithet frequently tossed at homeowners fighting new development. “Some people don’t like change, and instead of actually thinking about what could better everyone, they just think about themselves,” Fedak said.

“We talk about things like climate change, but the liberals in New York—while they’re talking about how awful global warming is going to be—they don’t recognize that that’s going to produce refugees both domestically and abroad, and, historically, cities have been the outlets where refugees flee to,” he said. “We need to plan ahead to house these populations who are going to be increasingly disaffected and increasingly dispersed.

“In my opinion, the way to get to true housing affordability is not necessarily by building affordable housing. It’s by building enough market-rate housing so that the market itself can cater to the demands of the population,” he said. Fedak also argued against mixed-income housing, saying, “If you plop a bunch of working-class people into a neighborhood that is extremely expensive, where do those people buy their groceries? They do not have the amenities they would in a working-class neighborhood.”

Notably, this view presumes that the goal of mixed-income housing is to allow school teachers and truck divers to live in wealthy neighborhoods. More often, the goal is to prevent investment bankers from gentrifying working-class neighborhoods. A new luxury high-rise in a blue-collar neighborhood can drive up property values, forcing longtime residents to move farther away.

For this reason, Durazo has argued against liberalizing zoning laws. “Changing zoning laws so that real estate developers can come up with a market approach does not address issues of health, affordability and segregation,” she said. “The fabric of communities is really going to be reshaped if this kind of one-size-fits-all zoning comes into play.”

Durazo supports more rent controls and, in some cases, mandates for affordable housing. Research has shown that rent controls actually drive up the cost of housing over the long term by discouraging new development. Affordable housing mandates, however, have been shown to be effective in suppressing rents.

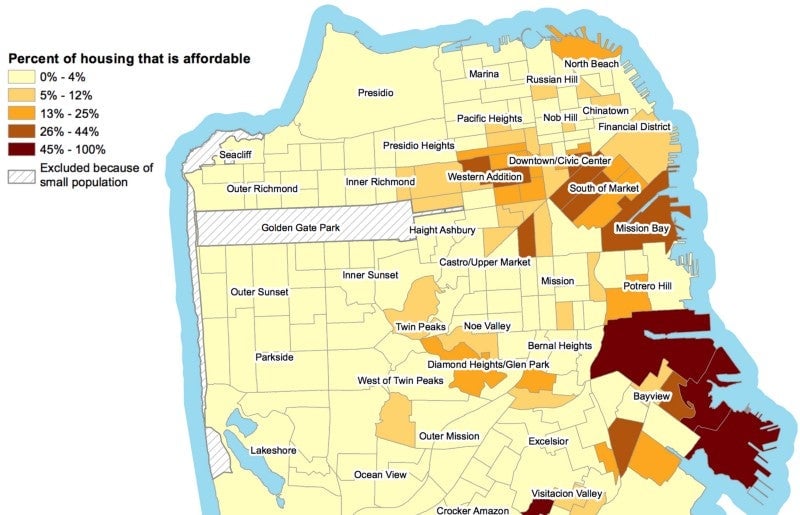

A study of the San Francisco housing market found that, to guard against gentrification, new developments should consist of 30% affordable housing. Doing so would not only keep the cost of housing in check, it would also put a dent in carbon pollution. Experts say that building low-income housing near train stations and bus stops does more to cut carbon pollution than building middle-income housing in the same place. That’s because, if displaced, working-class families move farther away from their job to find a home they can afford, and they end up driving more miles to work as a result.

Sometimes, it’s not a new luxury condo that is driving gentrification. When cities clean up pollution in working-class neighborhoods, that drives up property values, forcing longtime residents out—a phenomenon known as “green gentrification.” Many of those residents will end up moving to more polluted areas. To guard against green gentrification, cities must provide an adequate volume of affordable housing.

Climate change, ultimately, is a function of inequality. Few people would choose to live near a coal-fired power plant, an oil refinery, a natural gas drilling site or a crowded freeway. People live in polluted areas because they have no other option. In a sense, pollution depends on there being a class of people with so little money and power, they must put up with pollution. To keep climate change in check, advocates and policymakers must deal with economic inequality. The affordable housing crisis is just one expression of that problem, albeit an important one.

“We don’t say that you can only build affordable housing on cheap land, because the cheap land is inherently going to be in polluted areas,” said Guy. “If we’re going to build affordable housing, let’s create mixed-income communities.”

This post originally appeared on Nexus Media.