US immigration lawyers are shifting focus to prosecute people who’ve lived in the US longest

Trump administration officials have said any person in the US illegally should look over their shoulder. But data show the risk is greater for immigrants who have been in the US for longer—at least when it comes to being prosecuted in immigration court.

Trump administration officials have said any person in the US illegally should look over their shoulder. But data show the risk is greater for immigrants who have been in the US for longer—at least when it comes to being prosecuted in immigration court.

The number of cases filed by the US Department of Homeland Security against immigrants who’ve been in the US for more than two years has multiplied since Trump took office, according to recently-released data from the Transactional Records Access Clearing House at Syracuse University, or TRAC. Those filed against new arrivals, meanwhile, have dropped. The chart below shows how the shares of each type of case have changed from the Obama to the Trump administration.

Former president Barack Obama decided to focus on new arrivals after large numbers of Central Americans started showing up at the US-Mexico border—you can see that on the blue line on the chart starting around 2013. Like today, the immigration court system back then was beset by a gargantuan backlog. It could take years for a judge to hear a case, time during which an immigrant would get to stay in the US. The Obama administration’s thinking at the time was that if an immigrant was processed through court quickly and returned back home shortly after leaving, others would think twice before setting off on the same journey to the US.

The Obama administration also came up with a list of priority cases—people with a criminal record were at the top—and largely left well-established, law-abiding undocumented immigrants alone.

Trump has thrown that prosecutorial discretion out the window. The increase in cases against immigrants who’ve been in the US for years is a consequence of the wider net being cast by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, officials, says Jeremy McKinney an immigration lawyer in North Carolina. “This enforcement is the furthest thing from being smart,” he adds. “The bottom line is we have finite resources and already we’ve created this bottleneck because the growth of ICE has far outpaced the growth of the court system.”

Trump’s immigration enforcement zeal hasn’t helped. Since he took office, the number of pending cases has climbed at a faster clip than in previous years—by more than 30% to nearly 700,000 by March this year, TRAC data show.

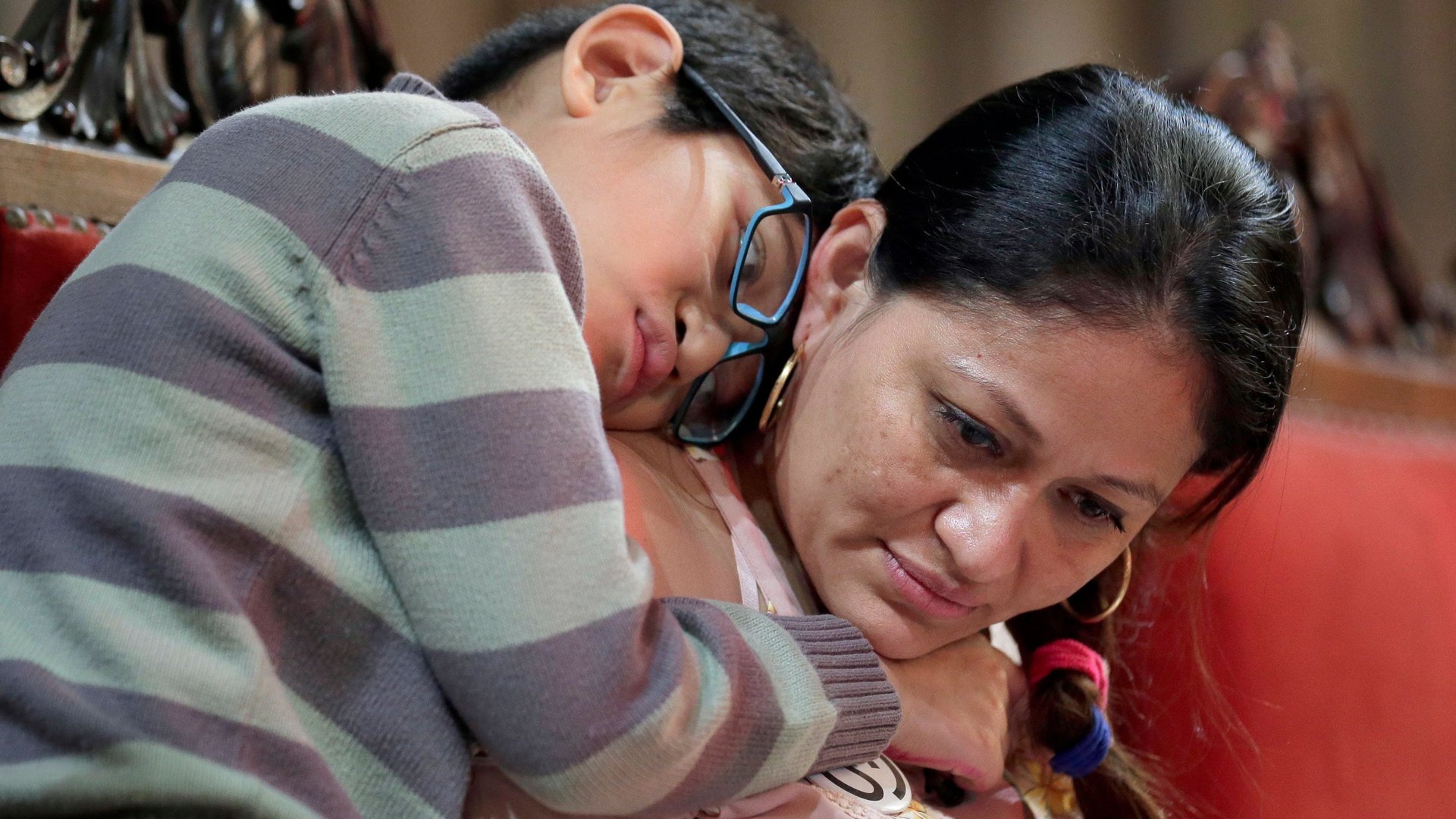

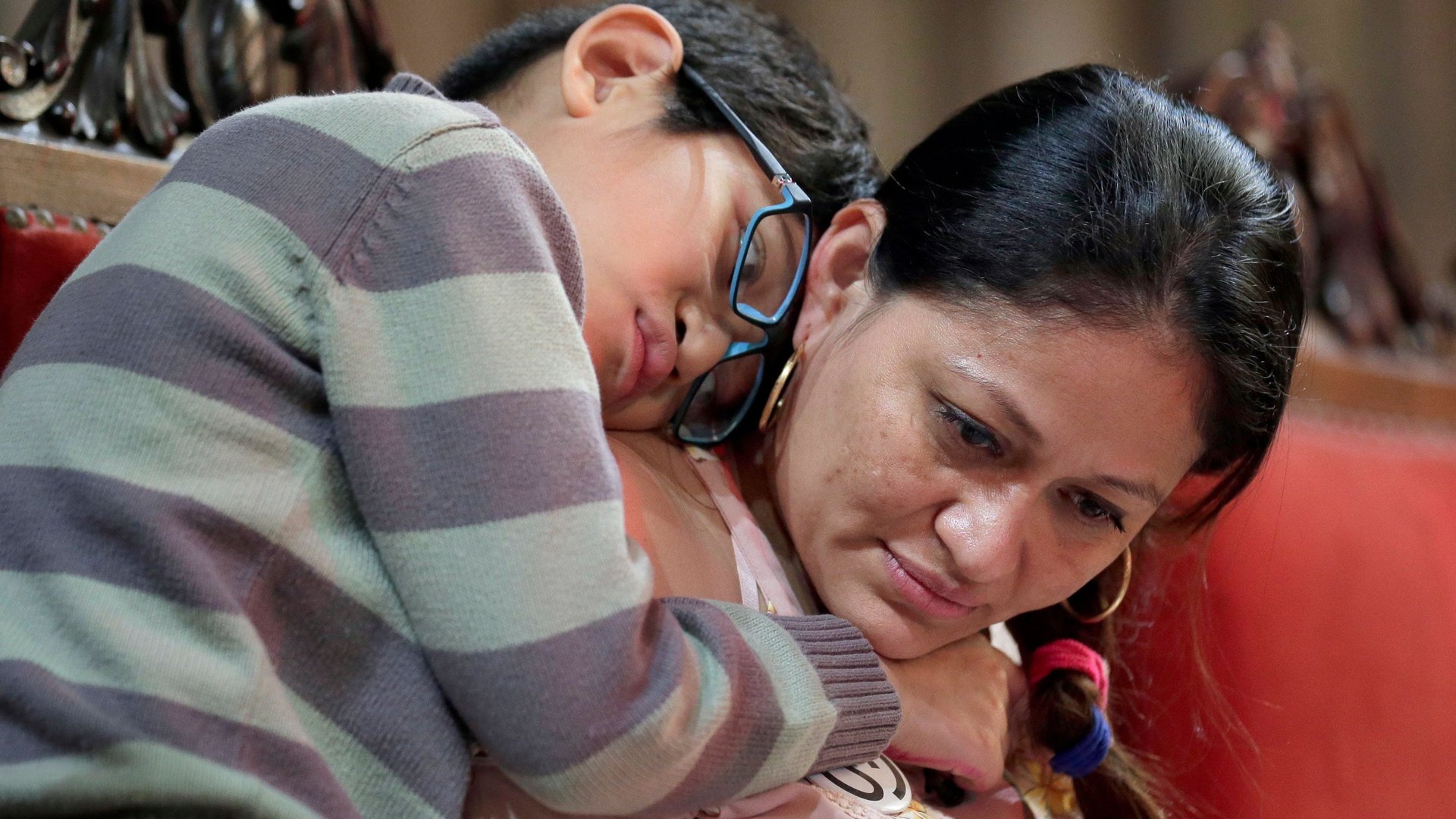

Targeting immigrants with more time in the US will likely slow down court proceedings even more. Immigrants who have been in the US for 10 years and meet a set of other criteria—including having no criminal record—can be eligible to permanently stay in the US. That means a judge has to weigh their case, says Niels Frenzen, a director of University of Southern California’s Immigration Clinic.

People with more US experience are also more adept at navigating the country’s legal system than a recent arrival, so they can make a better—and likely longer case—for themselves. “It’s a lot easier to deport someone who doesn’t know what their rights are or doesn’t have a lawyer,” adds Frenzen.