Brexit is breaking up Europe’s €10 billion plan to launch a new constellation of satellites

The United Kingdom’s awkward extraction from the European Union has extra-terrestrial dimensions.

The United Kingdom’s awkward extraction from the European Union has extra-terrestrial dimensions.

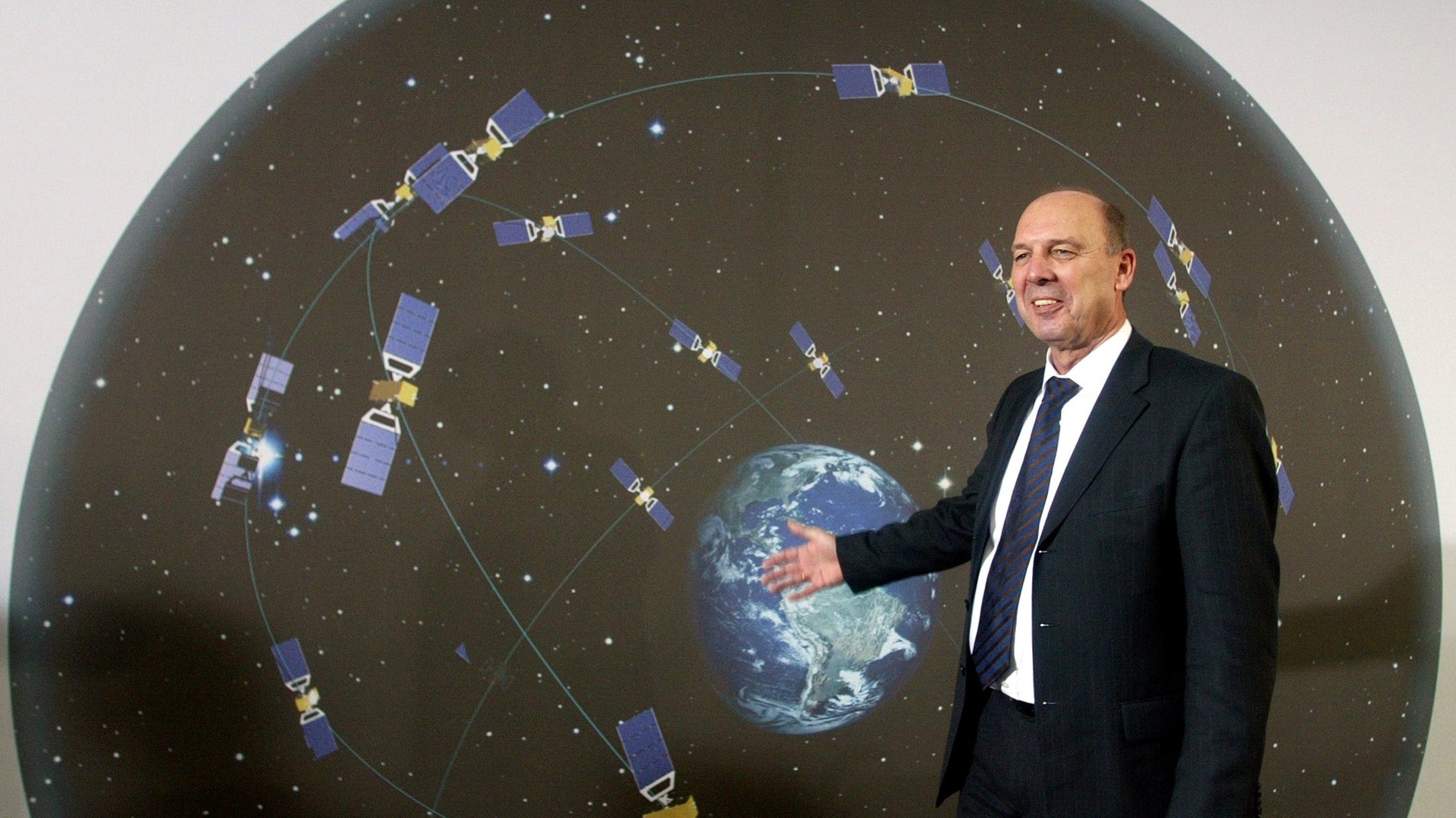

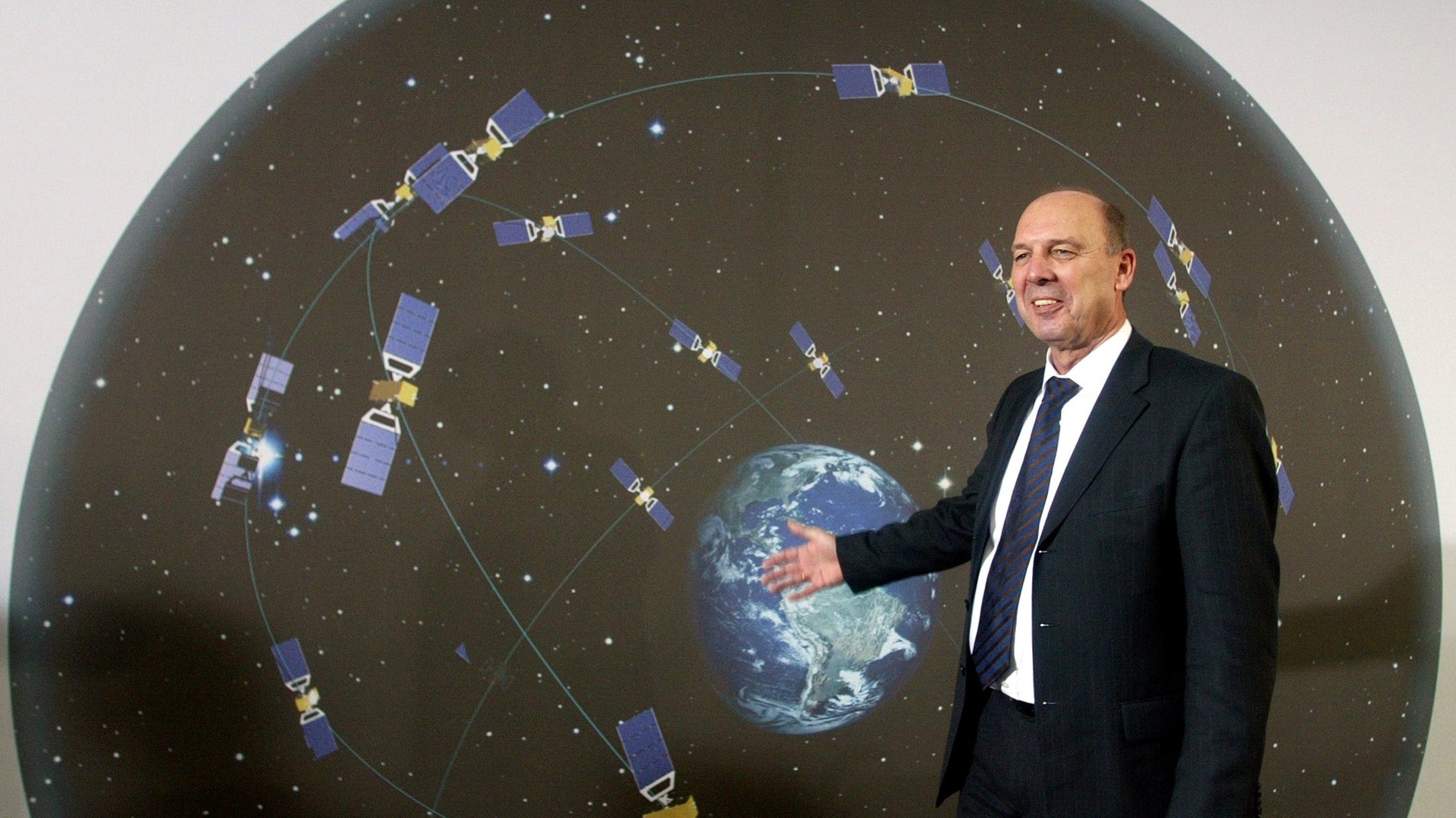

The European Space Agency is planning to launch a €10 billion constellation of satellites to provide navigation and synchronization signals to users on earth, akin to the US-operated Global Positioning System (GPS). Europe’s equivalent is called Galileo, and aims to provide vital infrastructure for everything from precision munitions and air traffic control to mobile phone apps and ATM transactions.

For civilians, the satellites will offer improved service. But for European governments, the satellites represent space power independent of the US, with the ability to provide situational awareness to their militaries themselves and deter jamming and other attempts to disrupt the signals from space.

Now, Airbus is saying that it will transfer work on the satellites and their ground systems from the United Kingdom to other EU member states. European officials decided that contractors on the project must be in the EU because they fear secret technical details about how their signals are encrypted could slip into the hands of rivals if production remains in the UK after Brexit.

This is more than just tit-for-tat squabbles over hundreds of jobs in advanced industry: British companies have been pioneers in designing small satellites, but they are deeply integrated with European industry and reliant on European and US launch vehicles. And, despite the rise of the private sector to orbit, government space agencies are still the biggest source of revenue for space companies. Being cut off from European space cooperation and contracts could cripple the UK’s space industry.

British officials say the idea threatens future security cooperation between the UK and the EU, and are now floating the idea of launching their own constellation, which would compete with GPS and Galileo, as well as Glonass, the Russian GPS system, and BeiDou, China’s navigation and timing satellite constellation. It’s hard to say if the tight-fisted UK government would be willing to float the expense of financing such a system; officials also say they will attempt to claw back the €1.4 billion the UK has already invested in Galileo.

Another option would be writing a new security agreement between the UK and the EU that would satisfy the secrecy concerns of Galileo’s architects. Like other aspects of the Brexit negotiations, it would effectively require creating a new framework to maintain the existing relationship between the UK and the EU. Frustration over the UK’s unilateral attempts to change the terms of the relationship is one reason European negotiators have drawn such a hard line on the navigation satellites.

While they still have a say, UK officials are threatening to disrupt procurement plans for the satellite constellation, already a project more than twelve years old. Further delays appear to be just one more way Britain’s on-going squabble with its neighbors will leave all parties falling behind in the global space race.