The people who will one day rebuild Venezuela

As Venezuelans head to the polls on May 20, no one knows when or how the dictatorship of president Nicolás Maduro will fall. But when it does, the country, especially in its first 180 days, will need to draw on a talented and diverse group of minds to fix the economy, the oil sector and more. Here are ten people who could lead the way.

As Venezuelans head to the polls on May 20, no one knows when or how the dictatorship of president Nicolás Maduro will fall. But when it does, the country, especially in its first 180 days, will need to draw on a talented and diverse group of minds to fix the economy, the oil sector and more. Here are ten people who could lead the way.

The Politician

David Smolansky is savvier than most when it comes to life in exile. The 32-year-old former mayor of El Hatillo was forced to leave Venezuela after the Maduro regime removed him from his post and threatened him with prison. The escape mirrored those of his grandparents, who fled the former Soviet Union in 1927, and his father, who left Fidel Castro’s Cuba in 1970.

Now in Washington, Smolansky has earned a reputation as a modest, thoughtful young leader who is interested in building consensus—rather than merely bolstering his own profile, a common failing in Venezuela’s fractured opposition.

Smolansky spends his time trying to influence foreign policies toward Venezuela, advocating a tough line on Maduro in meetings with other members of the exile community, multilateral organizations, ambassadors from Latin American countries, and members of the U.S. Congress.

Smolansky said he’ll meet with “anybody who is in favor of a country with democracy and liberty”—and that Washington provides a unique opportunity to do so, outside the intense media and social spotlight in Caracas that often makes conversations among different camps difficult. That type of pragmatism will come at a premium when Venezuelans are one day given the chance to rebuild.

The Captain of Industry

As the CEO of Venezuela’s most cherished national enterprise, Lorenzo Mendoza is more than just another businessman: he’s a public figure, a symbol of defiance, and one of the last people standing in the country’s beleaguered private sector.

His company holds pride of place in the Venezuelan imagination. Empresas Polar is Venezuela’s largest food company, producing half of the country’s arepa flour. Mendoza and the company are active in supporting social causes and small entrepreneurs throughout the country.

Government officials, meanwhile, would love to get their hands on Venezuela’s food production industry. But as ministers struggle to manage the more than 500 companies now under government control, they are wary of touching Polar: A takeover could exacerbate hungry in a country already mired in social, economic and political crisis. That would lead to more unrest.

Essentially, Polar’s competence protects it—and has led many to call on the 52-year-old Mendoza to run for president. Mendoza has declined, but he and other business leaders, toughened by 15 years of controls over currency, foreign trade and prices, will play a key role in Venezuela’s eventual recovery.

The Humanitarian

As a nutritionist, Susana Raffalli has made relieving hunger her life’s work. For more than two decades, that work has taken her around the world, to places like Pakistan, Myanmar and Nicaragua. But she never thought she’d have to do humanitarian relief in her own country.

An adviser to Caritas Venezuela, a Catholic organization that works with the most vulnerable Venezuelans, Raffalli is on the front line in documenting and addressing a health and nutrition crisis that grows worse by the day.

When Raffalli returned home seven years ago, she found a sort of “slow-onset emergency.” The causes of the disaster were very clear, Raffalli said: The economy was deteriorating. Venezuelans’ ability to secure a meal vanished. Prices skyrocketed due to inflation. Cash became scarce. Public transportation collapsed. What items were available sold at prohibitive black-market rates.

Now, nine out of 10 people cannot afford the food they need everyday. Over half the population lost more than 24 pounds last year. In the face of such a catastrophe, Raffalli is practical. She’s not waiting for a change in leadership, but a change of policy. She simply wants a Venezuela that can feed its people again.

The Oil Expert

Once the lifeblood of the economy, Venezuela’s oil industry is in a tailspin. Gustavo Baquero, who has spent a career in the upper echelons of the global oil business, has a plan to fix it.

In Venezuela Energética, or Energetic Venezuela, a book he co-wrote with prominent opposition leader Leopoldo López, Baquero lays out what it will take to turn around Venezuela’s suffering industry.

In large part, that means undoing the damage done to state oil company PDVSA over the last 15 years. In 2003, Hugo Chávez fired 18,000 PDVSA workers, nearly half its workforce, for protesting the company’s growing politicization. This meant that right as the price of oil spiked, Venezuela had few managers and experts in the field. Production stagnated; PDVSA, and Venezuela, never recovered.

Baquero has drawn on vast international experience in formulating a plan for Venezuela’s oil future. Though his work has taken him to Norway, his thoughts—and much of his energy—remain fixed on his home country. As for whether he’d return home to work in a more democratic government, Baquero has no doubts. “It’s a dream of mine,” he said.

The Entrepreneur

Marielena Polanco’s resumé reads as an object lesson on Maduro economics—and what would happen if Venezuela’s talented entrepreneurs were given space to succeed instead of being suppressed.

After seeing two businesses fail due to deteriorating economic and security conditions in Venezuela, Polanco was left with little choice. Like hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans in recent years—doctors, engineers, teachers, chefs—she and her husband left the country in search of opportunity, eventually settling in Colombia.

Luring back Polanco and others like her who have left will be a vital part of the Venezuela’s eventual recovery. But doing so will be a challenge, especially when it comes to the entrepreneurial class, as barriers to starting businesses remain.

Meanwhile, across the border Polanco is finding the same success she once enjoyed back home. In November 2017, she founded Refrilugar, a refrigerator repair business. The company has three part-time employees and generates sales around $2,000 a month. It’s a modest take, but a world away from Polanco’s prospects in Venezuela.

The Rights Advocate

Families whose arrested loved ones have disappeared. Protesters who emerge from a night in jail with a broken arm or leg. Opposition politicians locked up on bogus charges. The victims of chavista justice number in the hundreds of thousands.

And for more than 15 years, Alfredo Romero has been their champion.

Romero is the executive director of Foro Penal, a nonprofit organization of more than 150 attorneys and 4,000 volunteers whose job is to keep track of political prisoners and offer legal services to anyone who has been arbitrarily detained or tortured by the government.

According to Foro Penal’s latest count, Venezuelan authorities have jailed more than 12,000 people for politically motivated reasons since 2014. As of February 2018, the government was holding 231 political prisoners.

To restore the justice system, Romero suggested removing judges who used their offices to persecute political adversaries and setting up an international body to oversee legal aspects of a change in government. Until that day comes, Romero and his colleagues are keeping a more narrow focus. “Our goal is to increase the political costs of repression.”

The Economist

The director of Ecoanalítica, one of Venezuela’s most respected data and analysis firms, Asdrúbal Oliveros fully understands the pitfalls of negotiating with a government that has turned a blind eye to the suffering of its own people.

But as part of a younger generation of economists that has spent the vast majority of their adult lives under chavismo, he is one of few figures in Caracas capable of confronting the government and trying to find common ground at the same time.

In late 2017, he served as a consultant for the opposition in talks with the government in the Dominican Republic. It was a controversial decision, but Oliveros wasn’t there to fulfill some political ambition; he was there to offer economic guidance amid the worst contraction in Venezuela’s history. And if it meant even half a chance at pulling his country out of the depths, Oliveros do it again.

That ability to conduct civil dialogue with chavistas will be a valuable and perhaps underappreciated part of any future political transition. In the meantime, Oliveros is focused on trying to help businesses and everyday Venezuelans navigate what he called an obsolete economy, even as the likelihood of a turnaround grows ever more distant.

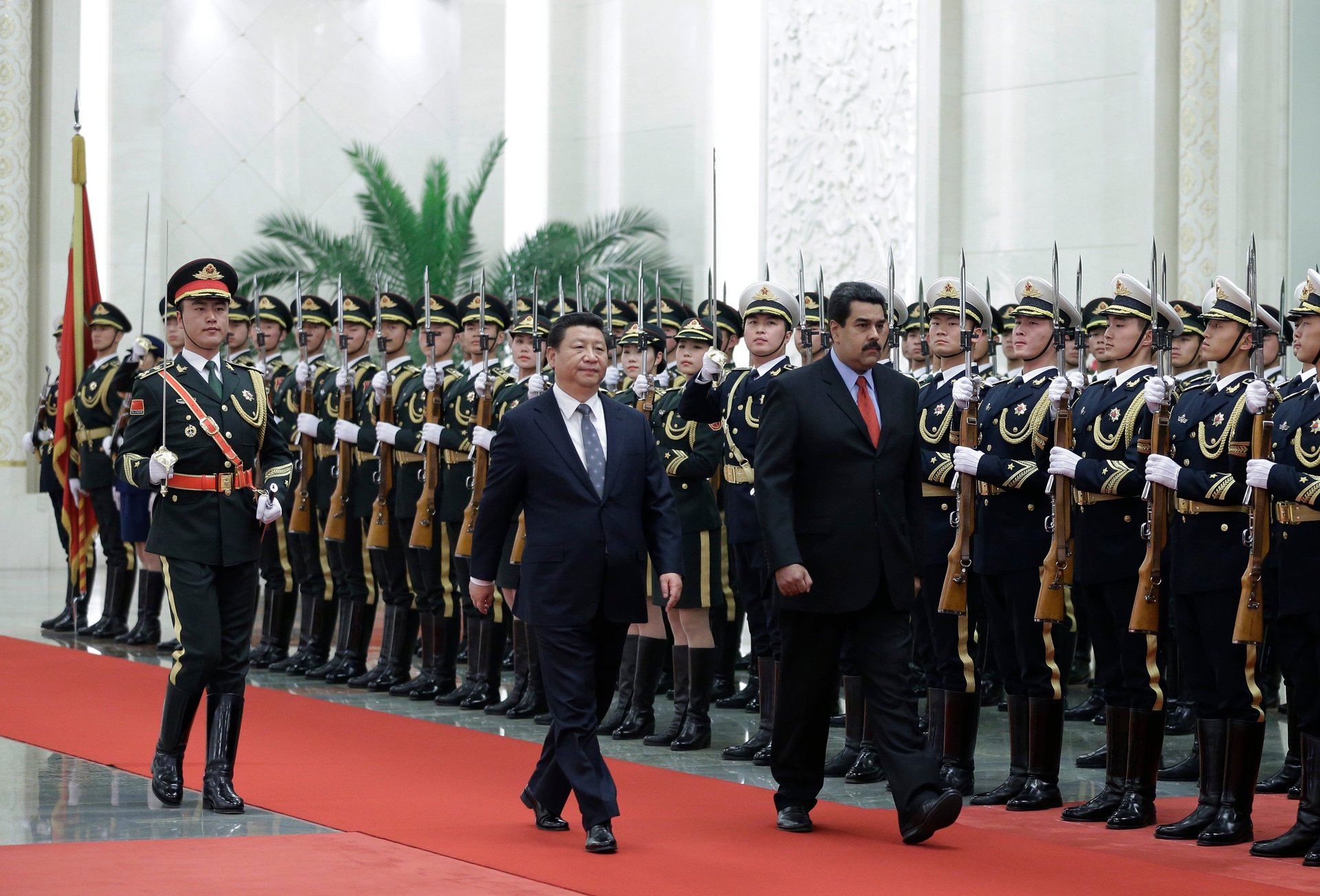

The Foreign Leader

Of all the non-Venezuelans with a say in Venezuela’s future, Chinese leader Xi Jinping may be the most important.

By now, the story of Chinese involvement in Venezuela is well-known. Beijing granted Caracas tens of billions of dollars in loans to lock in access to its oil. Those funds have been squandered and stolen, first by Hugo Chávez and now by Nicolás Maduro and their cronies. Today, Venezuela is not just bankrupt, but plagued by falling oil production and engaged in a fire sale of productive assets to service its debt.

It’s in no one’s interest, including China’s, that Venezuela collapse. But, unlike Russia, China is not so much interested in the politics above ground; China seeks the resources below ground. As a strategic matter, China needs Venezuelan oil to flow, and for the rapid oil production declines of recent years to be reversed. This will not occur with the current government in charge in Caracas.

The upshot: China has the resources and Xi has the power to underwrite a Venezuelan recovery. Western democracies cannot mobilize resources in the same way. In the coming battle of global systems and ideas, Venezuela may become a test case – with Xi as a leading protagonist.

The Educator

Once counted among Latin America’s top research institutions, Venezuela’s public universities are literally crumbling. Classrooms are left unlit, paint chips off walls, libraries are outdated and bathrooms don’t work.

That the education system is still functioning at all—or that schools like the Simon Bolívar University (USB) and the Central Venezuelan University can still crack top 50 lists of the region’s best universities—is a testament to professors like Mónica Kräuter.

Kräuter, 55, has taught chemistry at the USB for 20 years. But her advocacy for Venezuelan education took on a public bearing in 2014, after she published a study on the tear gas security forces were using on protesters then marching in the streets of Caracas.

At its core, rebuilding Venezuelan education after Maduro will depend on the same thing as most other sectors of society—the ability to earn a decent living.

“We all know being a professor isn’t lucrative anywhere in the world,” Kräuter said. “But it can’t be humiliating either.”

The Musician

For years, Venezuela’s most famous musician wanted absolutely nothing to do with politics.

Even as the economy and democracy crumbled, Gustavo Dudamel remained quiet, focusing instead on his stewardship of El Sistema, Venezuela’s widely admired, state-financed music program, which over the past four decades has taught thousands of youths from all socioeconomic backgrounds how to play an instrument. In a deeply polarized country, the 37-year-old conductor preferred to use music as a tool to bring people together.

But as anti-government protests swept the country in mid-2017, security forces shot and killed an 18-year-old viola player and El Sistema pupil named Armando Cañizales.

In response, Dudamel wrote a furious New York Times editorial condemning the violence. “I am not looking to take sides,” he said. “I am willing to take a stand.”

The incident illustrated how Venezuela has deteriorated to the point that perhaps no one can remain above the fray. But it also showed the kind of leadership that cultural icons can provide in times of national turmoil. Countries that successfully transition from authoritarian rule to democracy eventually go through a kind of national reckoning with their deep internal divisions—and that’s where Dudamel could be key.

This piece was originally published on Americas Quarterly.