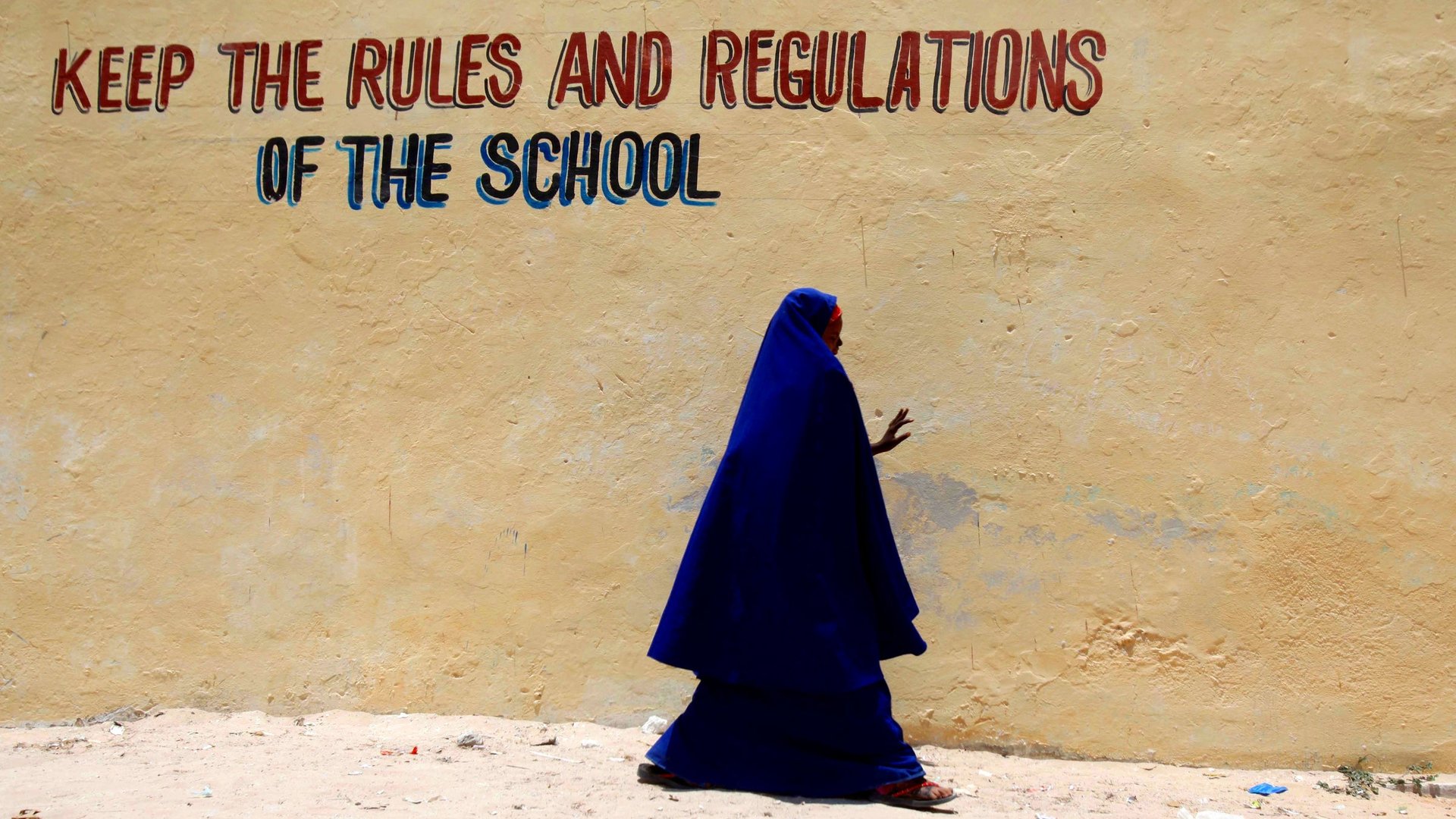

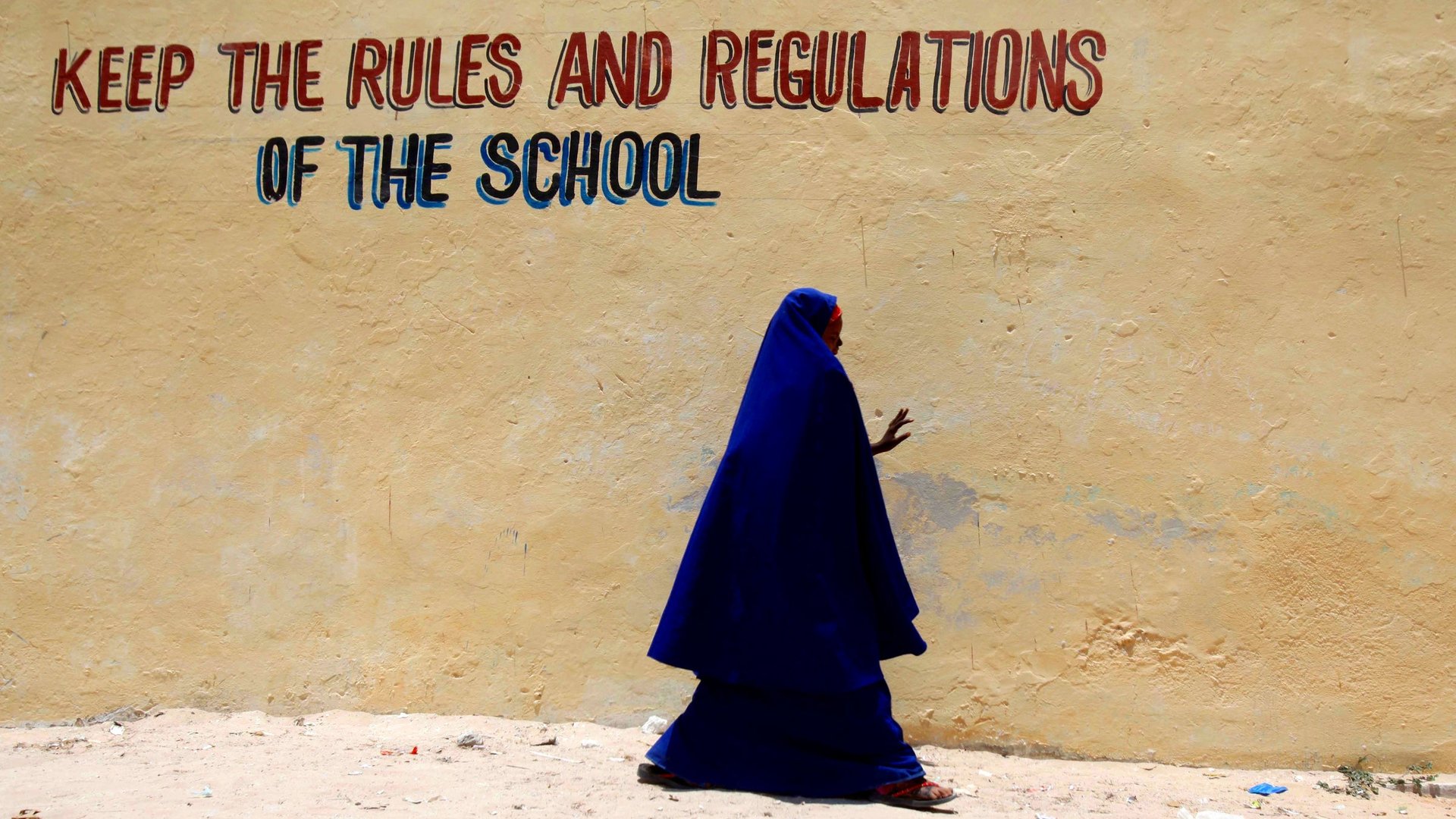

Can Somalia’s new female central banker break crony capitalism there?

Somalia beat the United States—and a host of other countries—at putting a woman in charge of its top financial institution. But even if the US Federal Reserve is behind on women’s empowerment, at least it isn’t facing the devastating effects of a drawn-out civil war.

Somalia beat the United States—and a host of other countries—at putting a woman in charge of its top financial institution. But even if the US Federal Reserve is behind on women’s empowerment, at least it isn’t facing the devastating effects of a drawn-out civil war.

Yussur Abrar, a former banker at Citigroup and AIG, became the governor of the central bank today, replacing Abdusalam Omer.

Omer left after getting into some hot water. A UN report accused him of serious laxity in managing the country’s cash-only financial system: Between September 2012 and April 2013, UN investigators say that 72% of withdrawals from the central bank went to individuals, typically government officials, and that $12 million of international aid sent to Somalia’s central bank during this time is unaccounted for.

The investigators put Omer, who took over the bank in January, at the heart of this mess. A Somali-American public administrator who helped pull the city of Washington, DC out of a financial crisis and became the chief of staff to DC mayor Anthony Williams, Omer resigned in 2001 after an investigation into fundraising irregularities. He later became the chief business officer of the school system there.

The UN says Omer helped design a new system to shift aid dispersement as a government official in charge of rebuilding Somalia’s fractured financial system. But when he was appointed to lead the central bank, he stopped reporting back to PriceWaterhouseCoopers, the international accounting firm charged with handling transactions between donors and the Somalian financial system.

Somalia hired a team of US lawyers to reply with the argument (pdf) that the UN’s investigation is bunk, the money isn’t missing, and that PWC failed in its fiduciary duties. Omer denies any mismanagement and says he resigned because of routine government restructuring.

In essence, the UN argues that Somalia’s transition government is caught up in a culture of casual corruption:

[P]rivate individuals, whether inside Government or outside, make requests to members of the leadership for private payments that cannot be resisted for personal or other reasons. The senior politician signs a note authorising payment that is honoured at the Ministry of Finance or the Central Bank directly. This custom is also called the “khaki envelope” procedure on account of the colour of the envelopes seen carried to the Ministry of Finance … as one senior official involved in Transitional Federal Government finances told the Monitoring Group: “Nothing gets done in this government without someone asking the question ‘Maxaa igu jiraa?’ (‘What’s in it for me?’)”.

Abrar has her work cut out for her in ways that few other central bankers do. She’s not worried so much about interest rates and market reaction as she is about constructing a modern financial system from the ground up. Somalia is deeply reliant on foreign aid, and if the international community loses trust in the transition government’s ability to dispense it, it could put one of the troubled nation’s main lifelines at risk.