Let finance handle your workplace wellness program, not HR

By now, the chances are overwhelming that your company administers a “workplace wellness” program that pays or requires employees to participate in health risk assessments (HRAs), biometric screens and/or regular physician visits. The idea is to reduce your health expenses by making your employees healthy enough to avoid “wellness-sensitive medical events,” like heart attacks.

By now, the chances are overwhelming that your company administers a “workplace wellness” program that pays or requires employees to participate in health risk assessments (HRAs), biometric screens and/or regular physician visits. The idea is to reduce your health expenses by making your employees healthy enough to avoid “wellness-sensitive medical events,” like heart attacks.

The reality is that those three activities are at best useless. At worst, they can even harm employees who take the advice too literally…and by doing so, drive up your health care spending.

The problem with these activities isn’t poor execution or failure to get “C-suite buy-in” the wellness industry excuses for poor performance. Quite the contrary, the problem is that the premise of wellness is irretrievably flawed: Wellness activities are focused on preventive care, but this country is already drowning in preventive care, and too much of anything—even prevention—is a bad idea.

HRAs, screenings and doctor visits

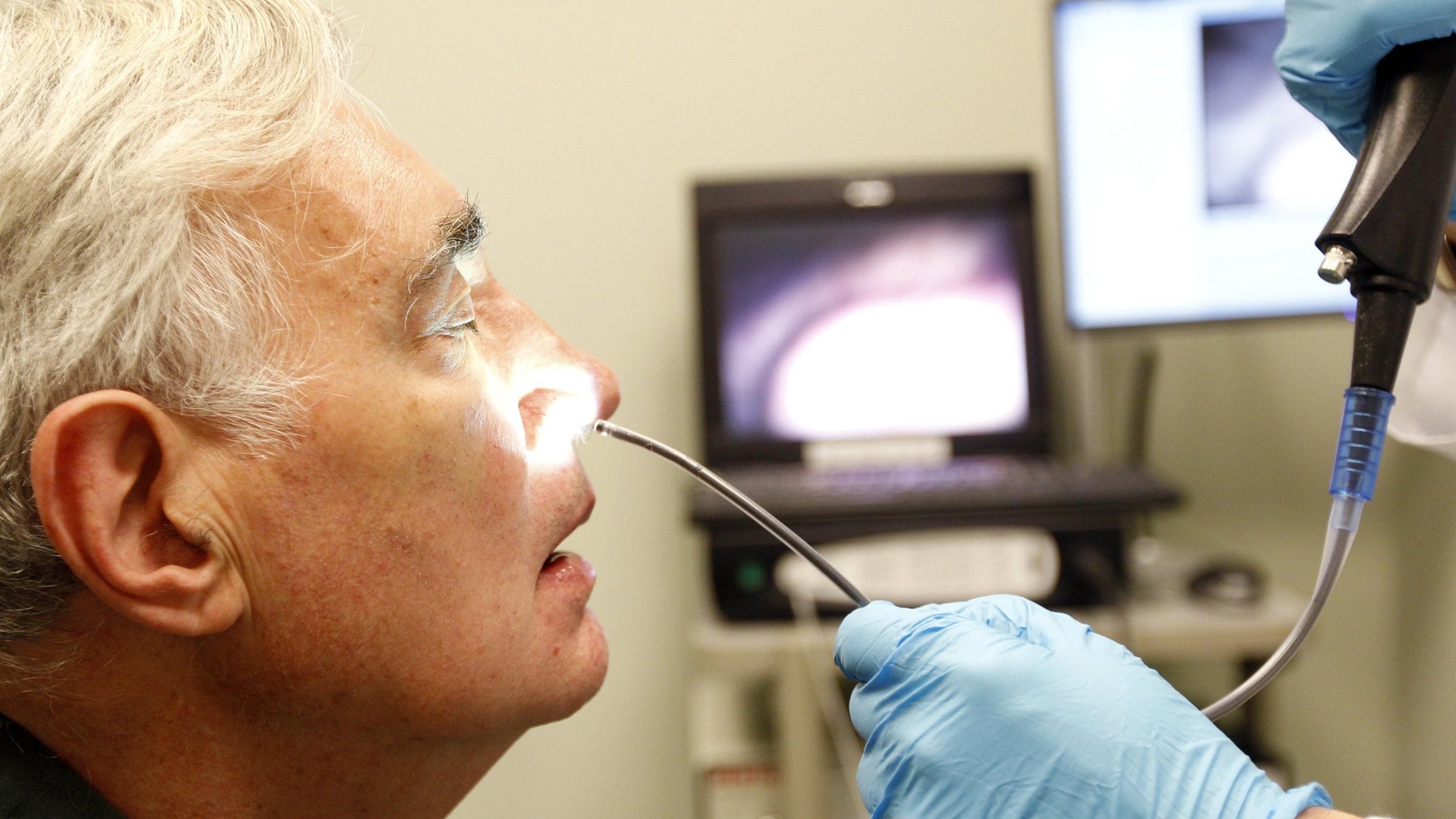

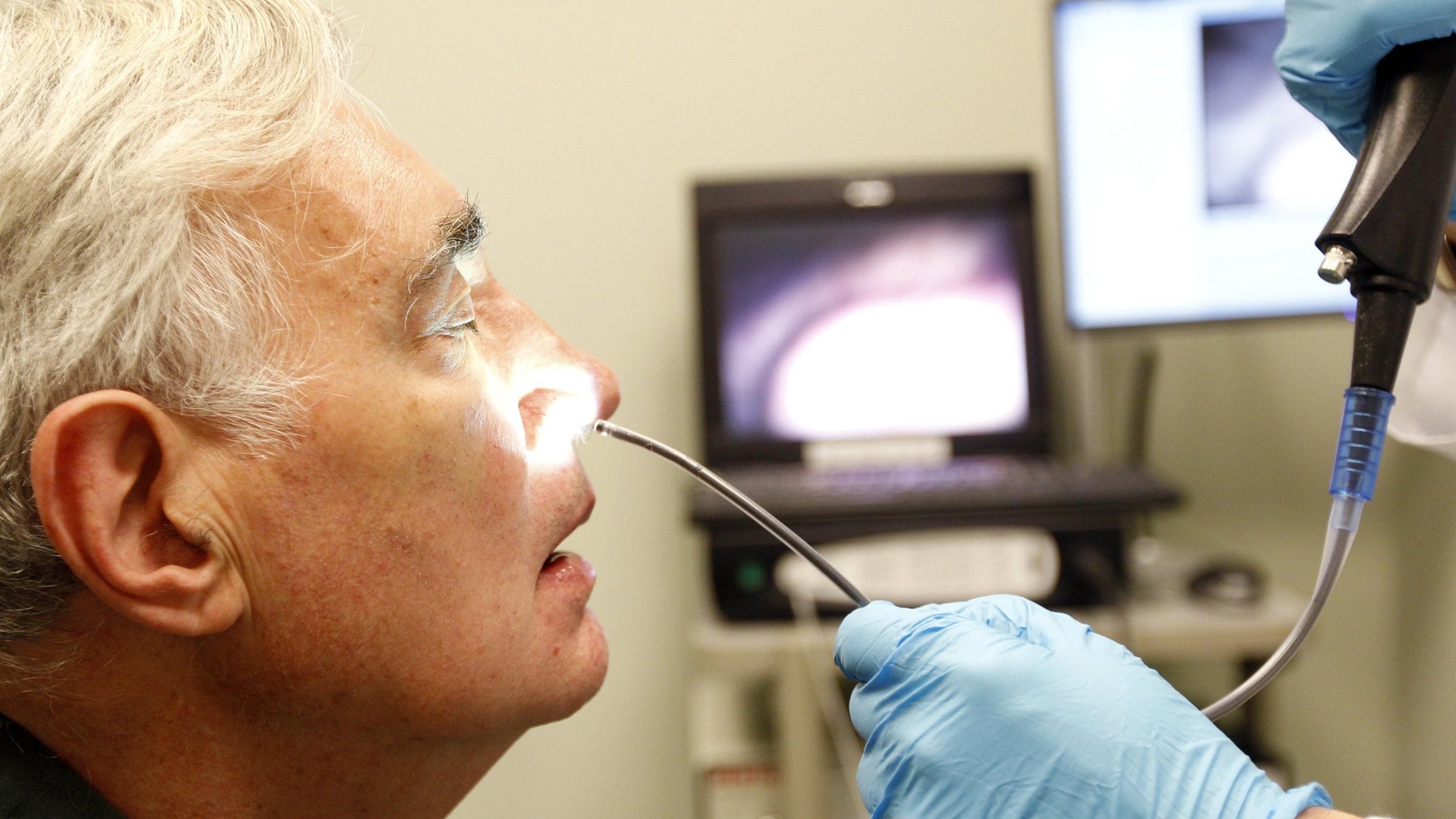

The advice from HRAs ranges from self-evident (vegetables are good for you and smoking isn’t) to simply incorrect. For instance, the Penn State HRA made national news by requiring testicle exams (like many other HRAs also do, just more adamantly), which the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against, while the prostate-specific antigen test, a favorite of the wellness industry, has been called a disaster by its own inventor. It’s rare to find an HRA in which even half of the medical recommendations (as opposed to the self-evident lifestyle recommendations) reflect federal guidelines. The large majority of us don’t need glucose testing, and, due to the likelihood of false positives, we should not get routine EKGs, but most HRAs advise them anyway.

Company-wide biometric screens generate even more potential for over-treatment by identifying mostly inconsequential health issues. For example, 40% of Nebraska state employees who were screened for cancer were told they were at high risk. Only 3% took steps to get better and overall claims costs allegedly fell the next year anyway, meaning these people weren’t at risk to begin with, and/or that the cost reduction figure was made up, like most others are. On the other hand, the low likelihood of actually preventing any consequential medical events means that the return on investment for screenings is always negative, as a matter of arithmetic, while as a matter of science, both the government and most experts oppose their annual use.

That brings us to preventive doctor visits, likely your largest and fastest-growing medical expense (pdf). The American Medical Association’s own journal says preventive visits increase diagnoses and drugs without improving health.

So why do your human resources executives embrace these programs nonetheless? Probably because they are not trained to identify invalid outcomes or even falsehoods right in the brochures; they buy what vendors sell them. Their advisors don’t help matters—often your own retained benefits consultant has undisclosed relationships with vendors that they “recommend,” while broker commissions are rarely disclosed but form a powerful incentive for “your” broker to place programs that generate income for them. No wonder economists call wellness a form of supplier-induced demand.

What to do instead

First, replace initiatives that you do to your workforce with initiatives that you do for your employees. The huge difference: If you need to pay or penalize people to generate participation, you are doing something to employees, not for them. Example: one mantra in our book Cracking Health Costs is to clean the restrooms more often. No employee has ever complained that the bathroom is too clean. Other possibilities include subsidizing healthier food choices in the cafeteria or providing on-site fitness facilities. These steps will increase employee morale by visibly improving their work experience and hence morale.

Second, it may be time to rethink reporting structures. The health benefit historically reported through HR when managing it was all about process, not math. It might be time to restructure so that HR handles only the process issues while quantitative matters are handled by finance professionals, who would retain their own consultants rather than the benefits consultants who helped create your company’s wellness mania in the first place.

To get additional data to support these recommendations, simply ask your HR executives: “After all these years of wellness programs designed to prevent heart attacks and other wellness-sensitive medical events, what has happened to our rate of wellness sensitive medical events?” You’ll learn that your staff has been charging ahead with wellness without even knowing the value of what they are trying to prevent. That will be all the data you need.