America’s top colleges are feeding the rich and keeping out the poor

Young gourmand-scholars of America have never had it better. Colleges across the US are staffing open-air kitchens with seasoned chefs and offering students Zagats-caliber dining experiences, according to the Daily Meal’s rankings of the “60 Best Colleges for Food in America for 2013.” Bowdoin College, in lobster-lousy Maine, came in first, followed by Washington University in St. Louis, which offers students sushi-rolling classes, among other things.

Young gourmand-scholars of America have never had it better. Colleges across the US are staffing open-air kitchens with seasoned chefs and offering students Zagats-caliber dining experiences, according to the Daily Meal’s rankings of the “60 Best Colleges for Food in America for 2013.” Bowdoin College, in lobster-lousy Maine, came in first, followed by Washington University in St. Louis, which offers students sushi-rolling classes, among other things.

Bowdoin and Washington University aren’t just foodie hubs; they also top the “best college” rankings. While Bowdoin ranks fourth on US News and World Report’s liberal arts college list, Washington University now ties Brown University at #14 on the national university rankings.

In fact, almost all of Daily Meal’s entries score high in the US News and World Report’s rankings. For example, every single Ivy League school made the list. Perhaps heirloom tomatoes boost brainpower. But more importantly, the overlap suggests that in their quest to lure full tuition-paying students, top colleges are locked in an amenities-spending arms race—in which catering to foodies, health nuts and gluten-shunners is a major theater of war.

That would be fine except, in many cases, top schools are installing tandoori ovens at the same time as they’re imposing huge financial burdens on their poorest students—when they enroll at all.

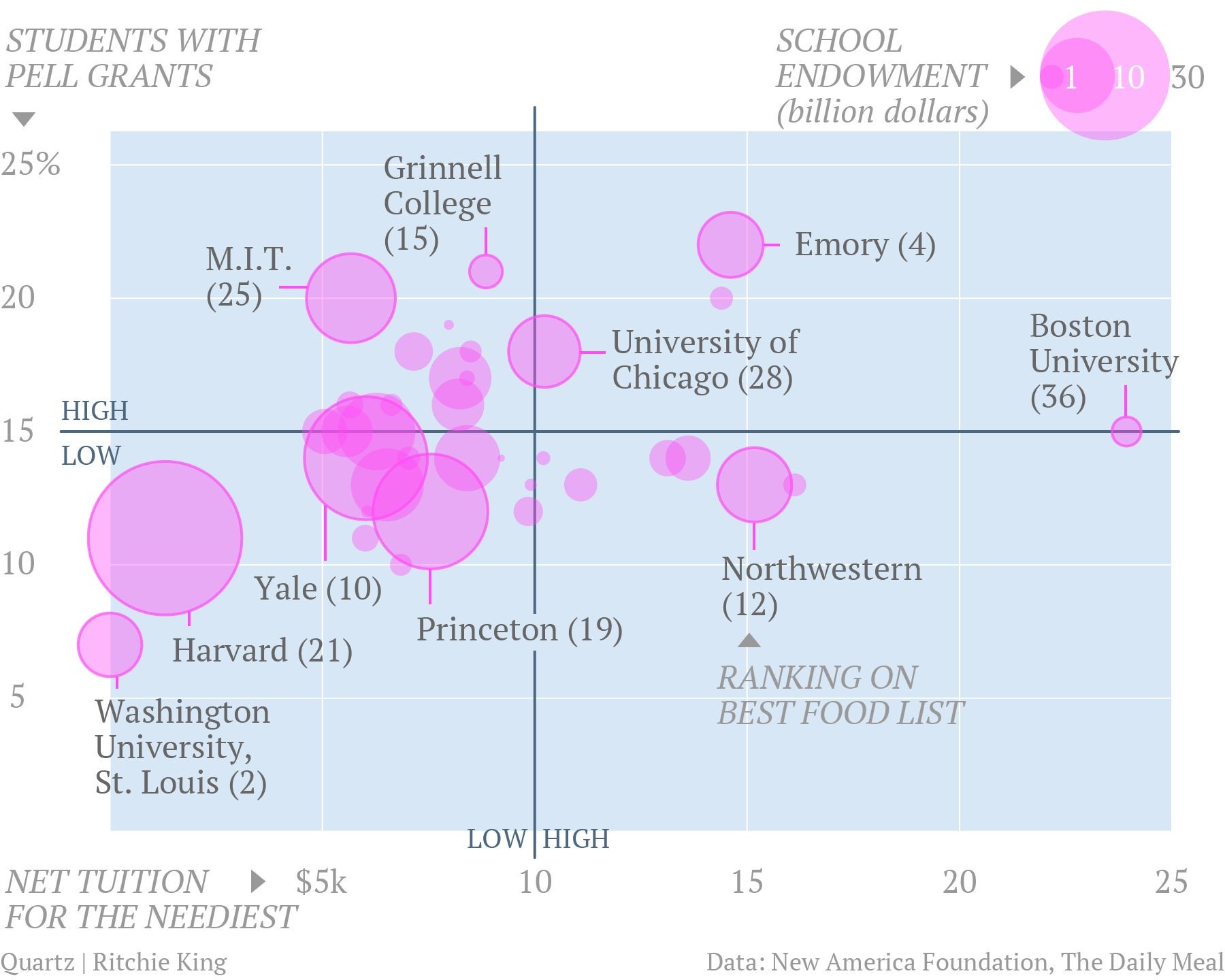

Using Pell Grants, which the US government gives to the neediest students, as proxy for poor students, Stephen Burd of the New America Foundation recently compared a school’s percentage of poor students and ”net price,” the amount students whose families make $30,000 or less in pay each year. We’ve recreated Burd’s analysis (pdf), as well as the school’s ranking on the Daily Meal list:

Not surprisingly, many colleges with fancy food also have huge endowments. Despite their high spending on dining and their massive coffers, many either enroll a tiny proportion of poor students or charge them more than half of what their families earned in a year—or both.

“[T]here is compelling evidence to suggest that many schools are engaged in an elaborate shell game: using Pell Grants to supplant institutional aid they would have provided to financially needy students otherwise, and then shifting these funds to help recruit wealthier students,” Burd argues. The goal is to attract students with high test scores that make the school more competitive, which boost the school’s prestige and in turn allow it to charge more for tuition.

In some cases, culinary excellence and aid-giving go hand-in-hand. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Grinnell and St. Olaf Colleges somehow manage to offer great food and aid to a high proportion of poor students enrolled.

But those are exceptions. Even among some of the most elite schools, the proportion of Pell Grant recipients remains low. With potential students weighing amenities, though, the culinary arms race rages on. For instance, Harvard, which the Daily Meal ranks #21, offers a “weekly Food Literacy Project Newsletter.” But #10-ranked Yale boasts “an entire dining series called ‘Reality Bites’ that offers the students programs on mixology, the best wine and meal pairings, and formal dining etiquette.” Time for Harvard to rustle up some sommeliers.