Angela Merkel scores big with voters, but now needs to win over bitter rivals to govern

In a campaign criticized for its lack of flair, the German federal election delivered a number of surprises on September 22nd. The preliminary results were announced in the early morning, at around 1:30am local time.

In a campaign criticized for its lack of flair, the German federal election delivered a number of surprises on September 22nd. The preliminary results were announced in the early morning, at around 1:30am local time.

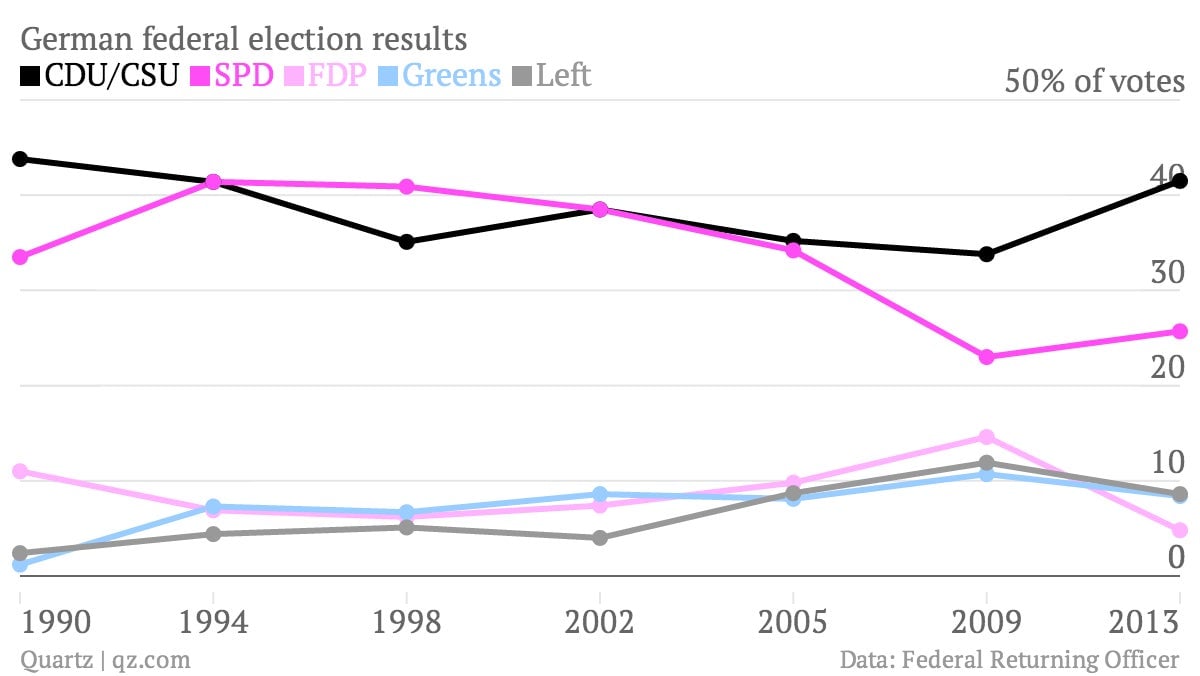

The election was a resounding personal victory for Angela Merkel, who is set for a third consecutive term as chancellor. With 42% of the vote, the result was the best for her party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), since 1990. Since Merkel first took power in 2005, she has seen fellow European leaders come and go, as frustrated voters punished incumbents perceived as bringing about the region’s financial crisis or not doing enough to fix it. Her cautious, steady leadership at the helm of the euro zone’s largest creditor received a thumping endorsement from voters this weekend.

It is not all smooth sailing, however. Merkel’s current coalition partner, the Free Democratic Party (FDP), crashed out of parliament after failing to get the 5% of votes necessary to gain representation. Thanks to this disastrous result, the FDP will not be in parliament for the first time since the party’s founding shortly after World War II.

Thus, a new Merkel-led government will rely on different partners. Her party came incredibly close to an absolute majority according to Germany’s complex electoral calculus, falling just a few seats short in the end. The main opposition group, comprised of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Green Party, won only 34% of the vote. They could, in theory, create a majority by partnering with the Left Party (9%), but both have ruled out an alliance with the ex-communists.

A grand coalition is in the works

Thus, the likely scenario is a bipartisan “grand coalition” between Merkel’s CDU and Peer Steinbrück’s SPD, the same set-up that followed Merkel’s first election victory in 2005. Since that experience led to a heavy defeat for the SPD in 2009, its members will be wary of entering an agreement on similar terms this time around.

For her part, Merkel told supporters that she will “aim for a stable majority.” Steinbrück, who was finance minister in the previous grand coalition, said only that “the ball is in Frau Merkel’s court.” This caginess will continue for days, if not weeks, as the parties spar over the policies and positions they can agree on if they go into government together. The parliament must meet within 30 days to appoint a chancellor and form a new government.

A bigger say from the left-leaning SPD in Germany’s government would imply less of a focus on austerity, a greater leniency towards struggling euro members like Greece, and more of a willingness to cede powers to the EU on things like banking regulation. At the same time, Merkel’s own party members, having come so close to governing alone, will not be in the mood to make concessions to their vanquished rivals. The upstart Alternative for Germany party, which ran on an anti-euro platform, nearly gained enough votes to make it into parliament. This will make Merkel’s colleagues wary of a challenge on their right if they drift too far to the center.

Thus, a definite victory for Angela Merkel masks significant challenges in building a viable government. Yet more indecision awaits, with Germans more reliant than ever on the pragmatism that has marked Merkel’s leadership so far.