5 reasons Germans ride 5 times more mass transit than Americans

When it comes to car use, there are a number of similarities between Germany and the United States. Both have high levels of vehicle ownership and saw motorization increase during postwar suburbanization. Both have extensive highway networks (Eisenhower later credited Germany’s autobahn with his desire to create the Interstate Highway System). Both countries have recently recognized that young people seem to be driving much less than their parents.

When it comes to car use, there are a number of similarities between Germany and the United States. Both have high levels of vehicle ownership and saw motorization increase during postwar suburbanization. Both have extensive highway networks (Eisenhower later credited Germany’s autobahn with his desire to create the Interstate Highway System). Both countries have recently recognized that young people seem to be driving much less than their parents.

When it comes to transit, however, the countries have gone in very different directions in the past fifty-some years. Today, transit use in the United States is much, much higher in cities than it is in rural areas. In Germany the disparity isn’t nearly as great. In small metro areas, Germans ride at 18 times the rate of Americans (a 7 percent share to .4 percent.) In major cities the difference remains high: transit use is nearly six times greater for Germans.

In a recent issue of the journal Transport Reviews, the (insanely prolific) research duo Ralph Buehler and John Pucher calculate that, all told, Germans are five times more likely than Americans to travel by mass transport [full PDF]. That’s after controlling for gender, age, employment, car ownership, population density, metro area size, and probably David Hasselhoff. Block me:

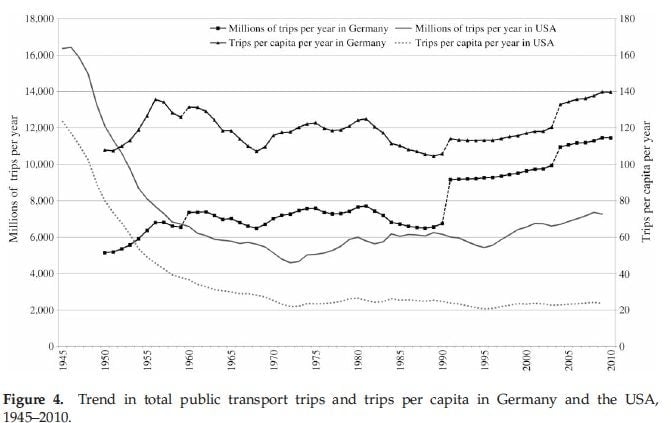

Over the past four decades, public transport has been far more successful in Germany than in the USA, with much greater growth in overall passenger volumes and in trips per capita. Even controlling for differences between the countries in demographics, socio-economics, and land use, logistic regressions show that Germans are five times as likely as Americans to make a trip by public transport.

Chart me:

And, since Buehler and Pucher offer five reasons for the divergence, list me:

- Expanded and improved service. While Germany’s transit mileage has decreased in recent times, as we pointed out last year, the country still has three times the service of the United States. Roughly 88 percent of Germans live within a kilometer of a transit stop, compared to 43 percent of Americans. German fleets are modern, reliable, and well-integrated (more on that in No. 3).

- Attractive fares. As we also pointed out last year, transit fares have increased in Germany — so much so that riders now cover three-quarters of operating costs. But most of that increase went to single-fare tickets. In the past two decades German transit authorities have arranged great discounts for children, the elderly, and students. Many employers have good rates too.

- Regional and intermodal coordination. German transit has what Buehler and Pucher call “full coordination of routes, schedules, and fares” in metro areas. That’s partly because the country has regional transit organizations that manage bus-rail transfers to minimize wait time and distance. The German metro also does a great job encouraging biking by offering parking and allowing bikes on trains.

- Car restrictions. German public policies are designed to discourage car ownership, driving, and parking. Unlike in the United States, where the federal gas tax has been stagnant since 1993, Germans pay very high fuel costs — with 60 percent going to taxes. (Sales tax on vehicles is also four times higher there.) And while American drivers fail to cover highway costs with user fees, with the Highway Trust Fund dipping into the general budget more every year, Germans cover 2.5 times government road expenditures through taxes.

- Land-use policies. According to Buehler and Pucher, German planning laws encourage dense, mixed-use development more than American ones do. This facilitates transit use and concurrent transit development. Generally speaking, German planning is also more integrated with transport than it is in the United States.

Add those five reasons together and you get five times more transit use. Of these factors, however, the researchers clearly believe No. 4 to be the most influential. They conclude their paper:

Without the necessary policies to restrict car use and make it more expensive, American public transport is doomed to remain a marginal means of transport, used mainly by those who have no other choice.

That might not be the best wording, because it sounds like you’re trying to punish drivers, rather than simply asking them to pay the true — and, especially in cities, extremely high — cost of owning a car. No surprise, the pro-highway folks at Reason took the statement just that way. (And, for some reason, thought a school bus was the best depiction of public transit.)Writes J.D. Tuccille:

Here’s a thought: If people will choose what you want them to choose only if you artificially hike the price and restrict the availability of alternatives, you might want to do some soul-searching about your personal comfort level with twisting people’s arms.

There’s little use engaging this rhetoric. Favorable car policies are equally artificial, of course, and restrict alternatives of their own. Still there’s a far more useful soul-search to be made based on the points of Buehler and Pucher. As they write, American transit use remains relatively low despite receiving $830 billion in public subsidies since 1975. That’s a lot of taxpayer money. What the researchers are really telling us here is that we aren’t necessarily getting the most for it.