We have a long history of portraying the horrors of war in creative ways—VR will be next

Where there have been humans, there has been war. Since the dawn of civilization, we have represented the pain of it through whatever medium is available to us. Whether it was early cave carvings, war paintings during the Napoleonic era, or photography in the American Civil War, we have continued to use new methods to portray its horrors.

Where there have been humans, there has been war. Since the dawn of civilization, we have represented the pain of it through whatever medium is available to us. Whether it was early cave carvings, war paintings during the Napoleonic era, or photography in the American Civil War, we have continued to use new methods to portray its horrors.

All these representations express a common desire: Take me there. Show me what I don’t know and can’t comprehend happens in other corners of the world. Make it real. Make it real so that in experiencing this reality we will change for the better, and war will end for good.

There has never been a more powerful medium to experience the horrible and inhumane than virtual reality. It is only a matter of time before we have our first war brought to us in this most immersive of mediums; one that will engage the totality of our senses, not just our eyes and ears. It will allow us the ability to truly “be there” in devastating and unprecedented ways. But even though VR brings with it new senses, the intention will be the same: to make us experience horrors, and then to end them.

Why do we take photographs of war?

It seems like a valid assumption that the closer we get to gruesome realities, the more we will learn, and the more we will understand the folly of our ways. But showing horrors doesn’t necessarily end them. When it comes to war art, each new medium has gone through the learning curve of balancing shock and developing a unique approach to storytelling.

Different approaches to representing violence and war have different impacts. The more effective ones are subtle and engage our inner storyteller; they help us make our own connections, rather than making them for us. The less effective ones simply shock and repel, causing the viewer to shut down; they paralyze us, our imaginations, and our ability for meaningful change.

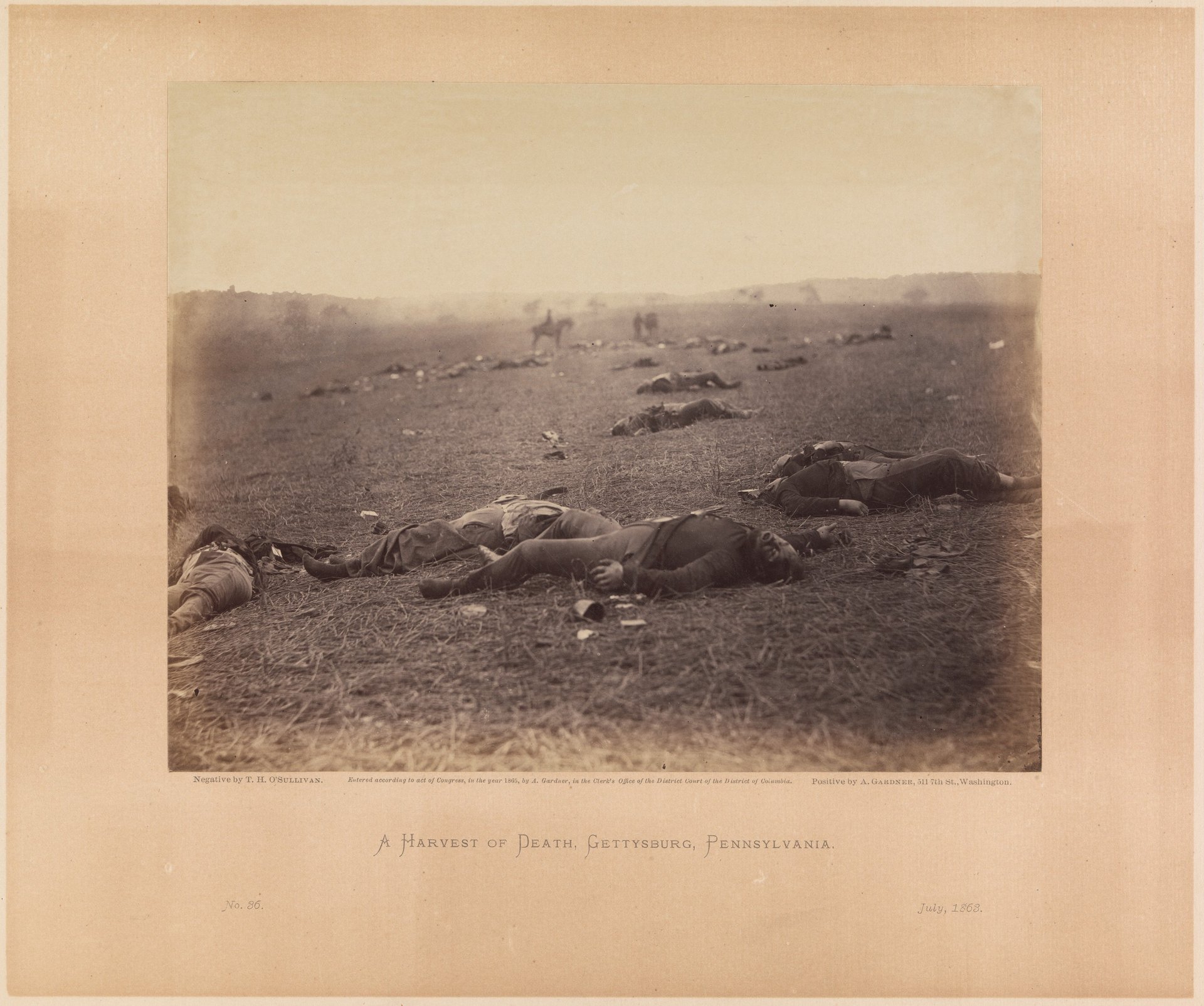

VR will not be the first medium to struggle with this balance. War photography also grappled with these challenges at its inception. Some of the earliest photographs were of dead bodies on the battlefield. No context. No names. Just mangled bodies. All with the hope that just the very act of showing these atrocities would stop war.

“Such pictures contains a useful moral: it shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry,” Alex Gardner wrote in 1860’s Photographic Sketchbook of War. “Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation!”

Ernst Friedrich’s War Against War (warning: very graphic images) furthered this direction by printing 40 of the most gruesome pictures from World War I. Again, his approach had little emphasis on storytelling. The book went on to be an international best seller, and by 1930 it had been printed in 10 editions in Germany, and pacifists the world over used it as a rallying cry to stop war once and for all.

Unfortunately, it did little to prevent the calamity of World War II.

Looking at these photos all these years later, when we have grown accustomed to stories coming with our pictures, they stir little within the viewer. We don’t know their names, their backgrounds, or the idiosyncrasies that made up their lives. As a result, we can’t connect; their ghastliness prevents us from finding a common ground.

Now contrast this approach to what is considered one of the most iconic and impactful images of the Great Depression: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother.” In this case, one needs to look and interpret pain rather than be stunned by it. Its impact lies in its ambiguity. What is she thinking? What’s happened? We have to fill in those blanks, and in doing so relate and feel more for the image and its subject.

Film, the next era of war art

This conceit—that images of horror prevent horror—didn’t stop with the still image. Vietnam brought fresh violence with the moving image, and broadcast it straight into homes. The first conflict to be experienced through video footage on TV, the Vietnam war introduced a new level of empathy to everyday citizens.

This continues to this day on television and laptop screens around the world. The war in Syria, with citizen-generated recordings of unfathomable and traumatic pain uploaded onto YouTube, allows for a whole new engagement with violence and pain that is not ours. Facebook also gives us the potential to see terrible things in real time as they are happening, such as the 2016 livestream of the murder of Philando Castile at the hands of the police. All these forms, but especially social media, have the intent to be seen and shared with the world so that we may be incensed to action.

Even though activists wish people would looks more closely at these damning images, there is evidence that this may in fact hurt more than it helps.

For one, we grow numb to these images. Public-health studies have long understood this. Over 60 years of studies have shown that shocking and sensational images used in public-health campaigns simply don’t work. They scare you and make it hard to take measured and rational decisions on your well-being.

Instead of being literal, the most effective images are abstract, like the “This is your brain on drugs” PSA that used the metaphor of a fried egg to show the effect of drugs on the brain. This was far more effective then showing a dead body of a junkie. (When the ad was heavily circulated, illicit drug use in kids aged 12-17 dropped from 3.2 million to 1.3 million.)

Likewise, what is widely considered the greatest film ever on the Holocaust, Shoah, doesn’t use archival footage. The film shows no pictures of death and suffering, instead evoking an emotional resonance through interviews and long languorous takes on the empty faces of survivors and collaborators. In one of the film’s most powerful moments, a survivor who sheared the hair of numerous women and children in the moments before their deaths in the gas chambers retells these stories while cutting someone’s hair in a barbershop in the Bronx.

Claude Lanzman, the director of Shoah, stated his film “would take up the ultimate challenge, and take the place of non-existent images of death in the gas chambers.” In a way, it was a strange blessing to not have those pictures: It made Lanzman rely on storytelling and craft, giving the film a power and poignancy that any image of dead Jewish prisoners in gas chambers could ever have.

Maus is another touchstone of empathy and art in portraying the Holocaust. It is a graphic novel that represents Jews as vermin, Nazis as dogs, and the Poles as pigs. It is a daring, disturbing, and fantastical choice. Though it feels jarring the first time you look at it, it has a subconscious poetic effect over the reader. You begin to realize that if you were seeing “real” people and not talking animals that you wouldn’t have the safe emotional distance necessary to engage with a story of such unimaginable horror. The abstraction and metaphor allows us to engage in a way that the real would never allow.

War art’s unintended consequences

Besides numbing us, images of death, violence, and violation can also unintentionally excite us. We don’t have to be sociopathic to feel this: This is Hollywood and the video-game industry’s bread and butter. Shocking and sensational images of war and suffering are increasingly appearing in our current media diet and have become hard to distinguish from our standard entertainment fare. This is precisely why the US army invests in violent movies and video games to lure potential recruits in—it’s a core part of their recruitment strategy. (Recruitment for the Navy even reportedly went up 500% after Top Gun was released.) As a result, these kinds of war films have become so normalized that they can titillate and seduce, rather than incite and enrage.

That’s the other problem with horrific pictures: They do not universally mean the same things to all people. It depends on what side you are on. If not distributed carefully and responsibly, they can end up serving a very different purpose than what they were intended for. While you and I may be horrified witnessing the murder of a black man, what would a racist feel? Would he feel glee? What about people on opposite sides of a struggle? Wouldn’t witnessing the death of your enemy be a kind of vindication, a satisfying revenge?

Take the image of the drowned refugee toddler on the coast of Turkey. For many, this was a turning point to understand the plight of refugees fleeing Syria. Yet the same picture of Aylan that was aimed at galvanizing Europe to accept more refugees was used by ISIS as a warning to those choosing to flee.

The next era of war art: virtual reality

Inevitably, all new media are eventually used to represent war: photography, radio, television, and, now, virtual reality. The assumption that merely representing war helps to prevent and discourage war is naïve. I was very cognizant of this when I started working in this burgeoning new medium in 2014, when I directed one of the first-ever documentaries in VR, Clouds Over Sidra, about a 12-year-old girl in a Syrian refugee camp. Given how immersive and overwhelming VR is, it was seductive to just show the pain, rather than learn the very difficult craft of telling a good story in VR. It was a new medium that required an entirely new approach to storytelling.

Clouds Over Sidra ended up doubling donations for Unicef and influencing powerful policy makers at the World Economic Forum at Davos, yet it shows nothing out of the ordinary, and isn’t what one would expect for a war VR film. It takes you on a tour of the camp. You see children playing soccer. The local bakery. Sidra at school. You can get inside her head—her consciousness—in a way no other media can. You come to understand that though everything seems normal, it is a prison of sorts. It is not home. This loss of innocence is what breaks people.

Ali Eslami’s award-winning VR experience Death Tolls, on the horrors of mass death, also does the unexpected. It similarly left many in tears without any pictures, just poetic data visualizations that played on VR’s inherent strengths of scale and place.

Getting into someone’s inner mind and understanding data in new ways only begins to scratch the surface of what makes VR so unique as a medium, and why it resonates with people unlike any other medium before it. My most recent VR experience, The Day The World Changed, co-created with Saschka Unseld, which, premiered earlier this month at the Tribeca Film Festival, allows, for the first time, the act of collectively bearing witness to testimonies from the US nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. Using the latest in avatar science and spatial sound technology, it introduces a whole new concept: of going through a documentary inside the documentary with other people who are also avatars, providing a whole new relationship of what a shared experience with history can be.

Storytelling matters—and even more so when you have a new medium that hacks your senses and transports you like nothing ever before. Cracking these new storytelling codes in VR will truly give us a better reflection on our own current reality because, it will allow us a space to think and to imagine. If we want to use a new representational medium to discourage war and violence, we first have to perfect the craft of telling stories about war and violence in that medium. Only then will we one day be able to make a difference.