Finland’s rank as the world’s happiest country is very upsetting in Finland

Finland, a perennial chart-topper on global rankings of well-being and prosperity, has just been named the world’s happiest country in the World Happiness Report. Finns are not happy about the news.

Finland, a perennial chart-topper on global rankings of well-being and prosperity, has just been named the world’s happiest country in the World Happiness Report. Finns are not happy about the news.

While Finland is often admired abroad for its progressive policies on work, family leave, and education, the praise is commonly met with skepticism at home. “If Finland is the best the EU can offer, we should all be very concerned,” former parliamentarian Risto Penttilä wrote in response (paywall) to the World Economic Forum naming Finland the bloc’s most competitive country in 2014.

Writing in Scientific American, Finnish researcher Frank Martela explores why Finland’s assessment of its own happiness is so different from that of outsiders—and why that may be a good thing for everyone.

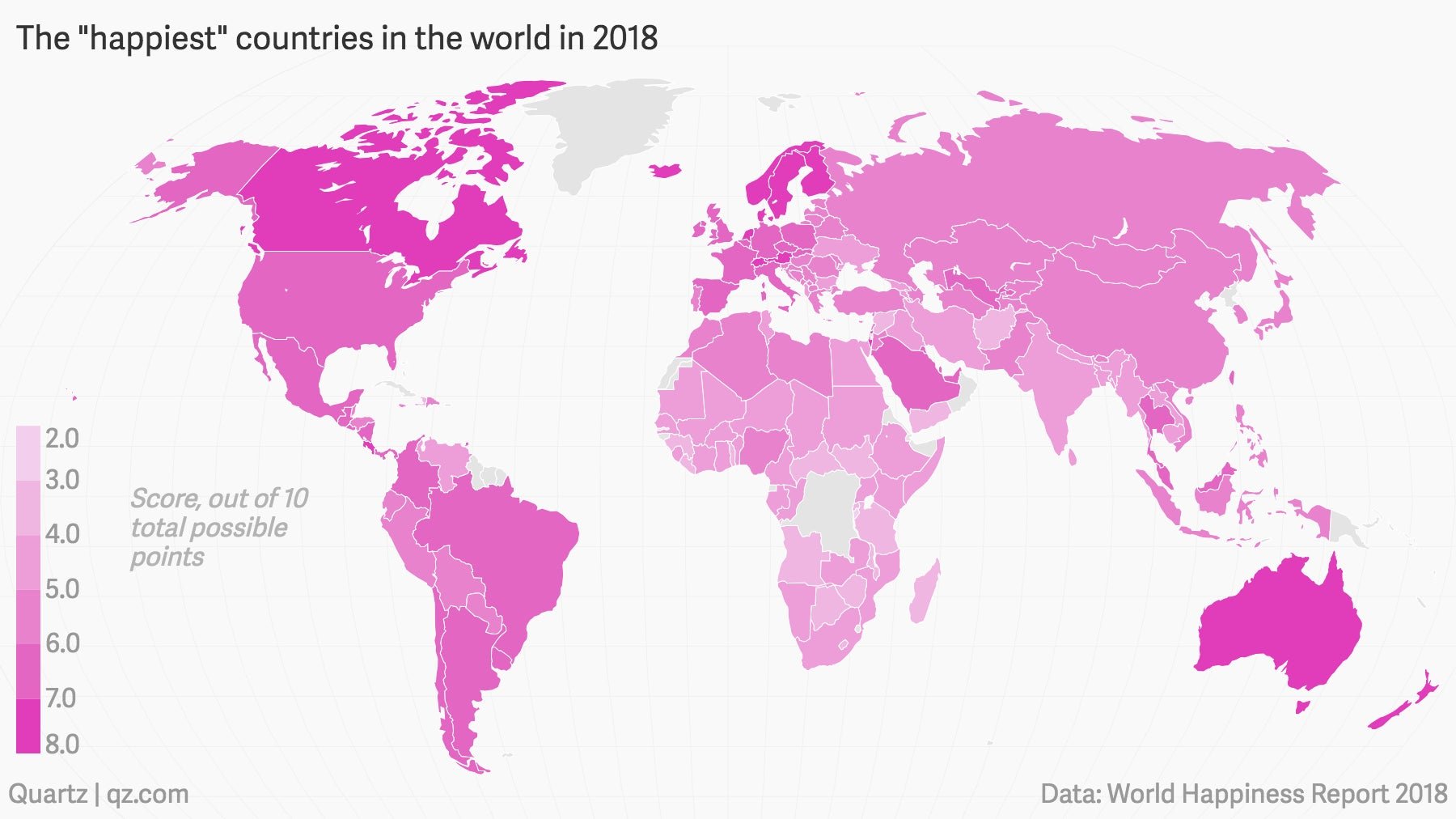

A product of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network, the World Happiness Report draws from Gallup polls that ask respondents to rate their lives on a scale from zero (worst possible existence) to 10 (fully actualized perfection).

Finns rated themselves an average of 7.632. The US average was 6.886; the average in Burundi, the least-happy nation, was 2.905.

Respondents weren’t asked why they rated themselves as they did. But the three economists who edited the report—Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University in the US, John F. Helliwell of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, and Richard Layard of the London School of Economics—pointed out several factors that tend to contribute to national well-being, including GDP per capita, life expectancy, lack of corruption, and social support.

Such factors make for a stable existence, but stability isn’t the same thing as happiness. As Martela writes, when people in different countries are asked how often they have positive emotions and experiences—in other words, how often they actually feel happy—Finland’s ranking plunges. The top 10 in Gallup’s Global Emotions report is typically dominated by Latin American countries. In contrast, Finland came in 36th in a 2013 Gallup survey of self-reported positive experiences.

But Finns’ wary view of their own happiness may have an upside, Martela writes. Comparison is the death of joy, an aphorism articulated by Mark Twain and backed up by research that finds people become less satisfied with their own lives when comparing them to others who seem to have it better. By downplaying their own good fortune, Martela suggests, Finns are sparing those of us elsewhere in the world the pain of envy and resentment.

“If happiness is the prevalence of positive emotions (let alone the displaying of them), Finland is not the happiest country. If happiness is the absence of depression, Finland is not the happiest country,” Martela wrote. “But if happiness is about a quiet satisfaction with one’s life conditions, then Finland, along with other Nordic countries, might very well be the best place to live.”