How Nike’s self-lacing shoe was created, in six questions

There’s a quick but memorable moment in the 1989 movie Back to the Future II where Marty McFly, an American teenager transported decades forward to 2015, encounters a futuristic pair of Nike hightop sneakers. He slips his feet into them, and to his amazement, they automatically cinch, the laces tightening around his feet.

There’s a quick but memorable moment in the 1989 movie Back to the Future II where Marty McFly, an American teenager transported decades forward to 2015, encounters a futuristic pair of Nike hightop sneakers. He slips his feet into them, and to his amazement, they automatically cinch, the laces tightening around his feet.

For a lot of sneaker fans, this idea—of auto-lacing sneakers—never left their heads. Finally, in the real 2015, Nike made the announcement they had waited decades for: It would release actual auto-lacing sneakers.

Even 26 years later, the Nike Mag, as the shoe became known, was still futuristic. Despite the many other advances in technology since the 1980s, our most efficient mechanism for lacing up sneakers remained our hands. But Nike had made the shoe real—for the most part anyway. When the Mag came out in 2016, it was only released in extremely limited quantity, in partnership with the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (named for the actor who played McFly, who is an activist and sufferer of the disease). And they closed much less quickly than the version in Back to the Future II.

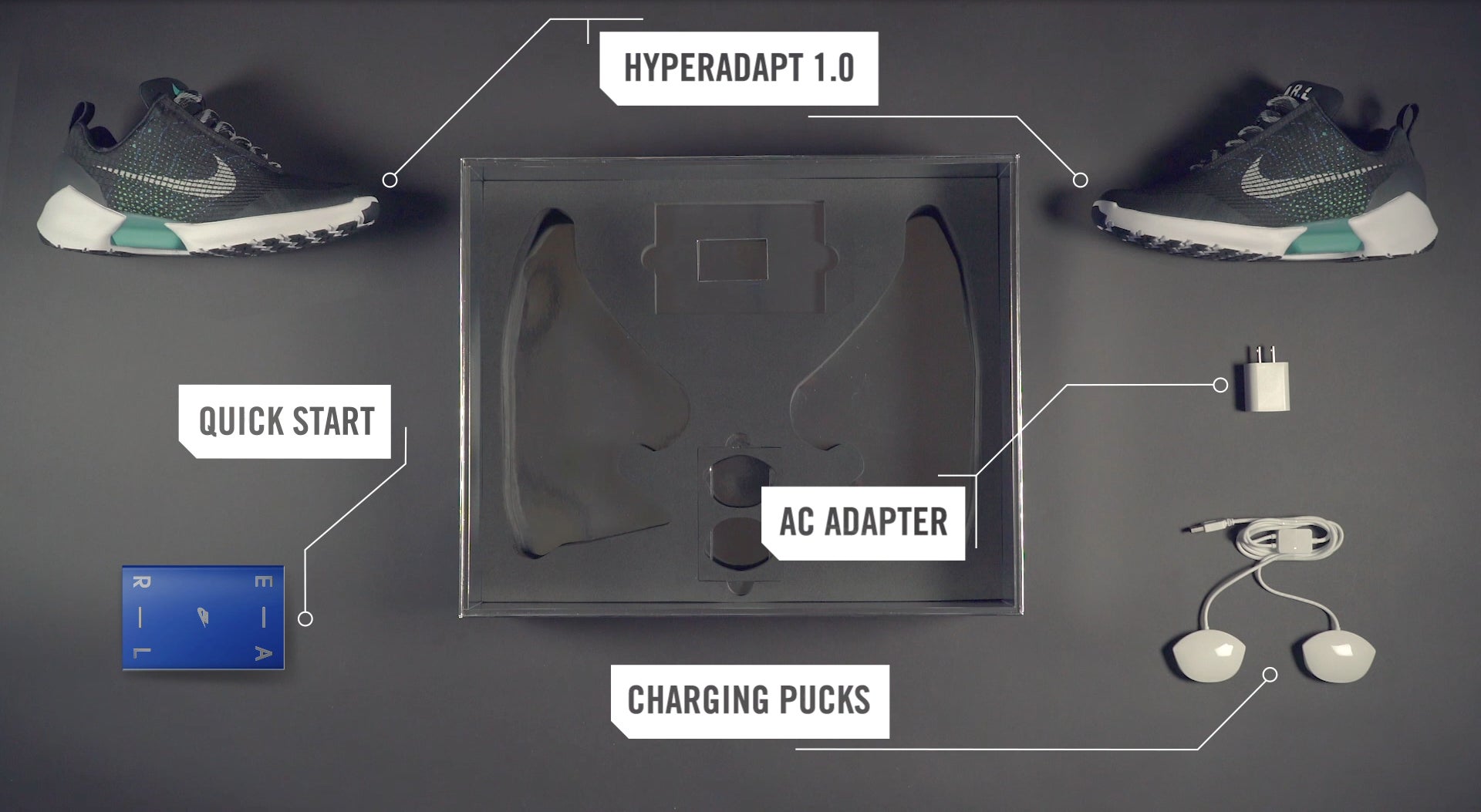

Still, the Nike Mag led directly to an auto-lacing shoe for athletes, called the HyperAdapt 1.0, which Nike intended for a bigger release. The auto-lacing technology, it turned out, had been a decade in the works, requiring a lot of testing along the way. The company kept at the concept not just for nostalgia’s sake, but also because it had come to believe that such adaptive footwear held a huge amount of potential in sports.

But there was no prior example to follow for how to build the shoes. Nike had to figure everything out itself. It had to innovate.

Nike had tapped a newcomer to the company, an engineer named Tiffany Beers (paywall), to lead the project. She worked on it amid her other assignments, without a deadline or a specified budget.

Beers, who left Nike in 2017 for a brief stint at Tesla, described the process to make auto-lacing real at a May 3 conference held by Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America (FDRA). There were plenty of daunting hurdles, but in each instance, she and her team were able to come up with creative and inventive ways to get over them.

Beers framed the story of how Nike built its futuristic, self-lacing sneaker as a series of six questions, describing her intensively collaborative process for addressing each one:

How do we pull the laces?

The most obvious challenge Nike faced was how to pull the laces to close the shoe. Beers’s background is in plastics engineering, which means she’s versed in things like injection molding. She knew nothing about motors, which seemed a necessary part of devising a solution. So she reached out to people who did.

We started doing technical bake offs. What that was, was I would reach out to the engineering firms or vendors or people that would potentially want to work on a project—even though I didn’t know what the problem I really wanted to solve was. I want you to pull a lace: How are you going to do that? I would reach out to these vendors and ask them to quote on it. How long would it take you? How would you go about it? And what would it cost me?

One big advantage to this approach, Beers realized, was that she and the team quickly saw the whole landscape of possible solutions, and got a sense of what creating one would cost. They also learned which partners would be best to work with.

Beers noted that she didn’t say she was reaching out from Nike. She wanted to see what the companies would propose without knowing who exactly they were talking to.

Where do we pull the laces?

Another conundrum Nike had to solve was where in the shoe they would pull the laces. Beers said by the time they got to this point, people in the company knew they were actually working on an auto-lacing shoe and excited about the idea. Beers team put the question out there and got back hundreds of ideas, but had no way to judge which of them might be viable.

Beers came up with a strategy to test them, based loosely on the Food Network show Cupcake Wars. Every one who brought a potential solution got an assignment. She told them:

Go build it for me in one hour. Bring it back to me. Tell me if the idea is still viable. If it’s still viable, tell me what makes it viable or what’s limiting it.

Beers called it “learning fast,” as opposed to “fail fast,” the unofficial motto of Silicon Valley. The team quickly figured out the limiting factors in building the shoe, like where they needed to wait for technology to advance. Motors and electromagnets had to get smaller before Nike could use them as it wanted, which is part of the reason the idea took so long to come to fruition.

To keep testing the ideas, Beers and the team kept handing out additional assignments. If the first idea was viable, the person or group that proposed it then had four hours to flesh it out and see if it still held up. The next round was two or three days. Finally, the ideas still standing got a week in which to actually be turned into a product.

“We went through this many, many times in the course of the HyperAdapt,” Beers said, “especially in learning how to set the lacing and how to get it to balance so that it fit multiple people well.”

When do we pull the laces?

Though a shoe that would automatically lace right after you put it on was the original goal, it wasn’t necessarily the best option for a real product. Beers says the team spent a lot of time considering the possibilities, such as putting buttons on the shoe so the user could decide when and how much to tighten it, or having a remote on a wristband that would offer the same control. Because the shoe was foremost about the user experience—as opposed to, say, performance or cost—that was an aspect they couldn’t afford to get wrong.

Again, they needed to test. But they couldn’t yet build a real auto-lacing shoe, so they simulated one:

We had in fact models of the HyperAdapt that were on remote. They were on remote that we threw together super quickly. We tested it on people in a matter of a couple of hours to find out if autolacing would be impactful and useful in what the customer wanted.

The awe on people’s faces when the shoes appeared to lace themselves was evidence that there was no substitute for genuine auto-lacing. “We knew where we were going. We knew how we were selling it,” Beers said, adding that simulating the user experience was a fast, inexpensive way of getting answers about how valuable the idea was.

The finished shoe uses sensors that can sense tension and the volume of the foot inside. When you put it on, the shoe closes to a comfortable amount of tension, forming around the shape of the wearer’s foot.

How do we put all these electronics in a shoe?

A sneaker isn’t the easiest place to embed an electronic lacing engine. There is limited space, moisture from sweat, and the normal impacts of walking and running.

The team building the HyperAdapt included an electrical engineer, a mechanical engineer, and a maker, who would build the different concepts. The maker had been making different versions of the HyperAdapt for years, and the main challenge he faced was burnout. His creativity and drive were starting to suffer.

Beers decided to set him an unrelated task that she hoped would restore his enthusiasm for the HyperAdapt project, too. He had to make a shoe—any shoe he wanted—that he could run five miles in. “But you cannot use one single material—not even adhesive—from footwear,” Beers told him. “You need to go to Home Depot to supply 100% of your materials.”

He took off, and in a few days he brought me back a pair of shoes that you would’ve never known the materials were from Home Depot. They were incredible, and he ran five miles in them and they looked great. […] He even incorporated the Home Depot logo in the top of the tongue from one of their bags.

The project reenergized him, and Beers said she’s been using the technique ever since, including in the brief time she spent as an engineer at Tesla.

How do we charge it?

Nobody wants to have to charge a pair of shoes. But Nike needed a way to charge the battery that would power the lacing engine if the HyperAdapt was ever to be a real shoe people would wear over and over.

The Nike staff had plenty of ideas for how to do it. The most popular was kinetic energy—the shoe will simply charge as you walk. But the technology was still being researched in universities and wasn’t close to being mass-produceable.

For assistance, Beers enlisted anyone at the Nike office who felt like helping:

We asked everyone in the office, and so at Nike it was probably 300 people. It doesn’t matter what you do. It doesn’t matter if you’re admin, or construction, or custodial, or a footwear maker, designer, executive, CEO—it does not matter. Everyone’s on a level playing field. Go out there, you have two weeks. Build me an idea of how to charge this, and you have one minute to pitch it back to me. One minute. If you can’t explain it in one minute, it’s not going to work.

More than 200 people participated, most of them working in teams, and Beers got back more than 50 different concepts, including multiple viable solutions. “Out of that it was so easy to pick the way we were going to charge the shoe,” she noted. If you buy the shoe today, it comes with “charging pucks,” as Nike explained in a first look it offered of the shoe in 2016.

The whole process took just two weeks. According to Beers, the key to its success was making it fun, rather than a stressful, judgmental process. The light attitude encouraged people to take part and try unexpected ideas.

How do we make it on deadline?

At the 2014 NBA finals, Nike designer Tinker Hatfield was talking to press and mentioned that the company was “making auto-lacing,” Beers recalled, and that it would be ready the next year. What Hatfield didn’t know was that the team had been told to stop work on the project because it wasn’t something they would bring to market in a viable time frame, Beers said. By that point they knew how to pull the laces, charge the lacing engine, and the other important details, but they hadn’t brought everything together into a compelling-enough shoe.

Hatfield, a senior member of the company, gave the team five weeks to put a product on the desk of CEO Mark Parker, Beers said. With the new deadline, the team had no choice but to focus:

We built literally a foam-core room in a hallway. We called it the Black Hole. We isolated ourselves. We got the best electrical-making engineer and the best chemical-making engineer that we could find from all the veterans that we had worked with over the years. We pulled them in for five weeks, and the five of us with the maker also worked together and we prototyped, prototyped, prototyped.

The shoe finally came together. Nike unveiled the HyperAdapt 1.0 to the public in 2016. At $720, it’s not something the average shopper will buy, but it has set Nike on a new path in adaptive products.

“The Nike HyperAdapt 1.0 is the first fully-functioning athletic shoe that electronically adjusts to the contours of your foot via adaptive lacing technology—providing a personal, customized fit that makes it feel like an extension of your body,” the company says of the sneaker.

In her talk at the recent FDRA summit, Beers said the strategies she used to overcome the challenges she described can work for any company, large or small, that needs to innovate fast, or wants to create an environment that promotes innovation.

She had another thought as well: “I think user experience is by far the most neglected piece of product sales,” she said. What other products could we rethink to feel as magical as a self-lacing sneaker?