If Alibaba is really gone, what’s the point of Hong Kong?

The forthcoming IPO of Alibaba is much more than just a $14 billion funding orgy for one of the hottest technology companies in China. Alibaba’s choice of a stock exchange to list its shares—in Hong Kong or, as seems increasingly likely, somewhere else—is a telltale indicator for the finance industry-beholden city.

The forthcoming IPO of Alibaba is much more than just a $14 billion funding orgy for one of the hottest technology companies in China. Alibaba’s choice of a stock exchange to list its shares—in Hong Kong or, as seems increasingly likely, somewhere else—is a telltale indicator for the finance industry-beholden city.

The internet commerce giant let it be known that it wanted its current executives to control the company after it goes public, and that it will not list in Hong Kong unless the exchange relaxes a rule prohibiting dual-stock listings. Today, Alibaba took its toughest swing yet, saying through unnamed sources that talks with Hong Kong were over, and that it is headed to New York.

Alibaba’s demands, which flew in the face of the city’s hard-won reputation for shareholder protection and the rule of law, created a knotty dilemma for the Hong Kong Stock Exchange: If it bent rules for Alibaba, how could it still claim to be an investor-friendly haven?

Losing the IPO raises even more troubling questions. Is Hong Kong really the financial gateway to China? Or will increasingly muscular moves from the mainland and competition from New York and Singapore result in high-flying companies like Alibaba bypassing Hong Kong altogether?

Alibaba’s troubling demands

Alibaba has been one of China’s biggest private enterprise success stories. Started by a former teacher, Jack Ma, the “world’s biggest bazaar” had revenues of $4.1 billion in 2012, and it has dominated the Chinese e-commerce industry by connecting businesses and their clients.

The company told the Hong Kong Exchange it wanted its existing leadership to maintain control over the board after an IPO, by allowing a management committee to nominate a majority of board members. That violated the spirit of the “one share, one vote” principle that Hong Kong has long insisted upon for its listed companies.

Alibaba isn’t state-owned, and its requests came without any overt political backing from Beijing, banking sources told Quartz. But with Beijing’s influence felt everywhere in Hong Kong, from the upcoming 2017 elections (Beijing recently ruled that city residents can’t choose their own candidates) to residents’ fears they could be sucked into China’s internet crackdown, the demands seemed menacing to some old-school Hong Kong financiers.

David Webb, a former Hong Kong Exchange director who is an outspoken advocate for shareholder rights in Hong Kong, wrote recently that Alibaba’s message boiled down to “let us pick our own rules”:

There is an element of China-think in the so-called “partnership” proposal; China is a nation with a Constitution which bakes in leadership by the Communist Party which picks its own successors. If the HK regulators make an exception for one new listing, then many future applicants will want the same thing, and many existing listed companies will complain that they should be allowed to do it too.

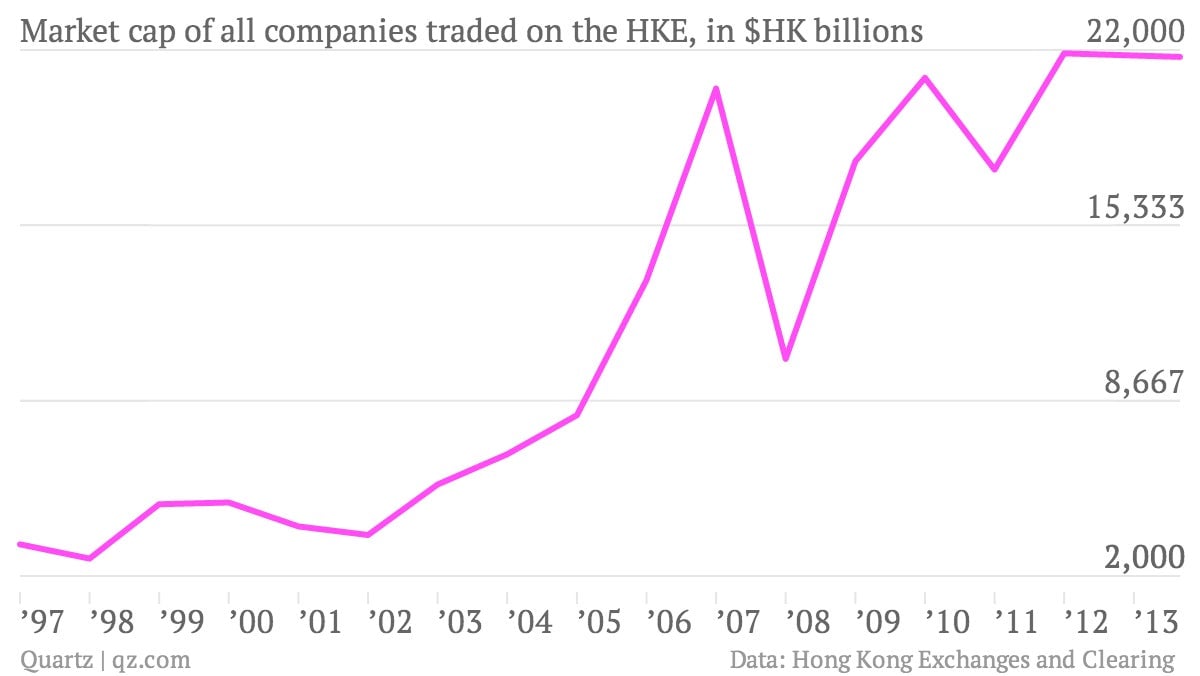

The demise of Hong Kong as a financial sector has been predicted again and again since the handover of the former British colony to China in 1997. Since then, Hong Kong has mostly thrived, becoming the world’s biggest IPO market from 2009 to 2011 as Chinese companies rushed to list shares, and drawing the international financial firms that were keen to tap into the Chinese markets.

But it is under siege. The exchange is “fighting a two-front war” to “show it is more Chinese than Shanghai and more offshore than Singapore,” said David C. Donald, a professor of law at The Chinese University of Hong Kong and author of a book on the exchange.

There’s a third front as well: Hong Kong is battling with the United States, where the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq have poured money and people into China to win new listings, with considerable success even before they took the pole position for the Alibaba listing.

Hong Kong’s reluctance to change its rules to cater to Alibaba may reflect the fact that US stock exchange rules are overly lax, as DealBook’s Steven Davidoff wrote on Tuesday. But even Hong Kong Exchange CEO Charles Li implied today in a long, somewhat strange blog post about a dream he had that maybe it is time for Hong Kong to change.

Weighed down by history

Stocks have been traded in Hong Kong since 1891, and traditions are deeply entrenched: There are dozens of seats for physical trading held by family-owned brokers, and trading still halts for a one-hour lunch break—though in a concession to modernity the break is only half of what it was two years ago.

The exchange’s hallowed practices also have plenty of critics. The underlying trading technology is so slow that big trades can take minutes to be processed, bankers say—aeons compared to the millisecond-sensitive systems of other exchanges. It has an antiquated closing mechanism that takes the median of the last five trading prices of a stock to determine its closing price, which creates volatility and leaves it open to manipulation. And its “cornerstone investor” system, which guarantees prominent investors early access to IPO shares in order to display their name on the prospectus to boost credibility and interest is fraught with potential conflicts.

The exchange has tried to address these issues, by starting a technology upgrade last year and new guidelines for cornerstone investors in March, among other measures.

The Beijing relationship

Since the 1997 handover, the exchange and Hong Kong’s market regulator have moved ever-closer to Beijing, which is ultimately responsible for its survival. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s fortunes have been so tied to the Chinese IPO market that the as public offerings dried up in 2012, net profits dipped by 20%.

A $2.2 billion deal for the London Metals Exchange last year was criticized as over-valued and poorly structured, but the LME has provided much-needed ballast. Second quarter profits were up 10% at the exchange, mostly because of 14% of revenues that came from the LME.

It may see another bump in listings before the end of this year as Chinese banks, an asset management company and a dairy go public, raising about $14 billion, according to the Wall Street Journal.

But there’s just no getting around the fact that the Alibaba listing is the hottest deal going.

The exchange had to stick to its guns because of concerns that “people won’t make a nuanced distinction between Hong Kong and China,” said a Hong Kong-based capital markets banker for a major Wall Street bank. Hong Kong’s regulators and exchange executives needed to “step up and say ‘This is special, and we need to show people we are really serious about market integrity,'” he said.

But, he added, if Hong Kong ends up losing out on Alibaba, “That would really hurt.”