The world’s biggest cargo shipper says trade is back

The Maersk Line, which handles 15% of the world’s shipping, says trade is back.

The Maersk Line, which handles 15% of the world’s shipping, says trade is back.

It had better hope so: The Danish freight line spent $3.7 billion ordering mega-freighters just two years ago, anticipating a pickup in economic activity, and if trade doesn’t pick up—or regulators don’t approve a cargo-sharing alliance with Maersk’s biggest European competitors—they’ll have lots of empty ships on their hands.

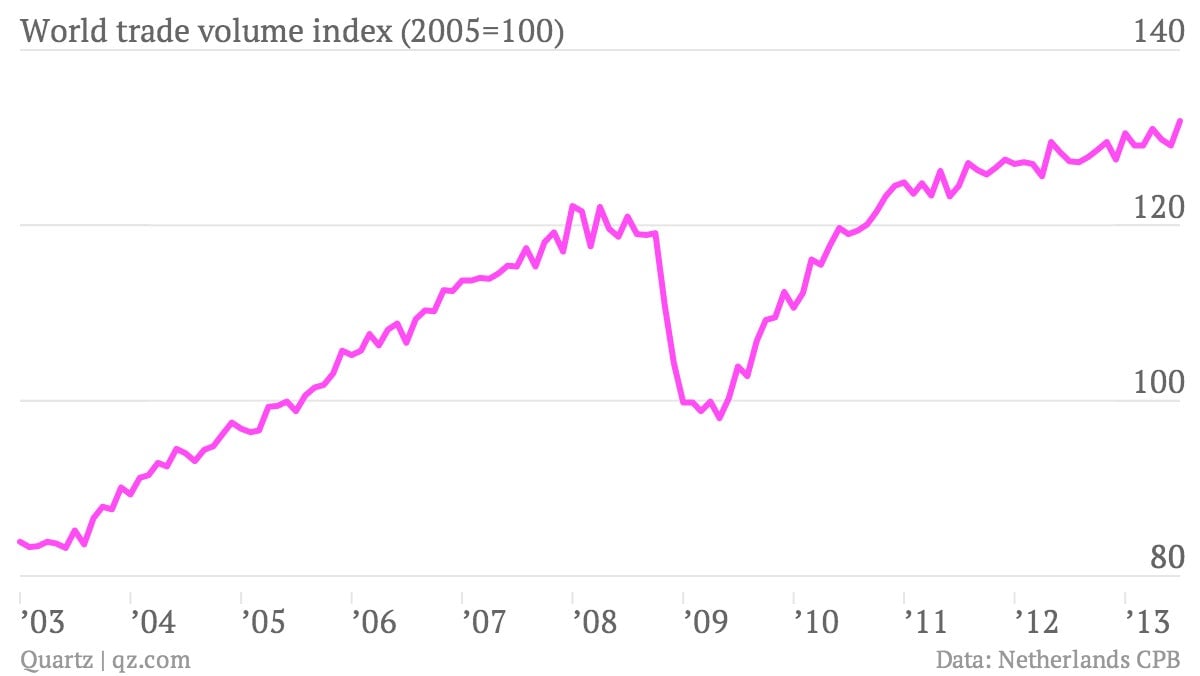

It’s easy to see why Maersk would’ve been hopeful in 2011 in the chart below, but the rate of trade growth slowed in 2012. Still, trade picked up in July, the most recent month we have data from the Netherlands, which tracks global trade volume:

The new container ships, called Triple-E’s, are designed for the Asia-Europe route, and can carry 18,000 containers, apparently the equivalent of 180 million iPads. But, between Europe’s debt crisis and recession, and the slowdown in growth in Asia, Maersk officials were forced to admit that their forecast for container demand was too high, with the route running at 10% under capacity. That left them unable to raise prices.

Today, Maersk forecasts the demand for containers will increase 4% to 6% in the next two years, suggesting that this is the bottom of the trade cycle.

But the company’s big hope for goosing flagging profits is an agreement, now under regulatory scrutiny by European officials, to ally with France’s CMA CGM and Switzerland’s Mediterranean Shipping Company to reduce the number of vessels plying the Asia-Europe route to 250 from 300. That will allow the three firms to raise prices, and Mearsk to take advantage of cost-cutting opportunities with the new Triple-Es, which consume less fuel than older, smaller ships in the firm’s fleet.