How to save the world from climate change with $50,000 and an ocean-going robot

On a dreary day for climate change news, here’s a reason for hope: robots.

On a dreary day for climate change news, here’s a reason for hope: robots.

Specifically, sea-faring robots that might be the key to understanding how the world’s oceans are absorbing rising levels of carbon dioxide that are cooking the planet beyond the point of no return, as the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated unequivocally today.

While climate scientists are dead certain that humans are responsible for the rapid increase in global temperatures, they are far less sure about how the oceans absorb half the carbon spewed from everything from coal-fired power plants in China to cows in California.

That’s because the oceans are, obviously, big places. It’s exceedingly expensive to deploy research vessels to conduct scientific investigations into the mechanisms responsible for greenhouse gas absorption and the impact of using the seven seas as humanity’s carbon garbage dump. One well-equipped and staffed ship alone can cost $55,000 a day to operate.

Enter a University of Texas marine scientist named Tracy Villareal and four wave-and-solar-powered robots named Piccard Maru, Fontaine Maru, Papa Maru and Benjamin.

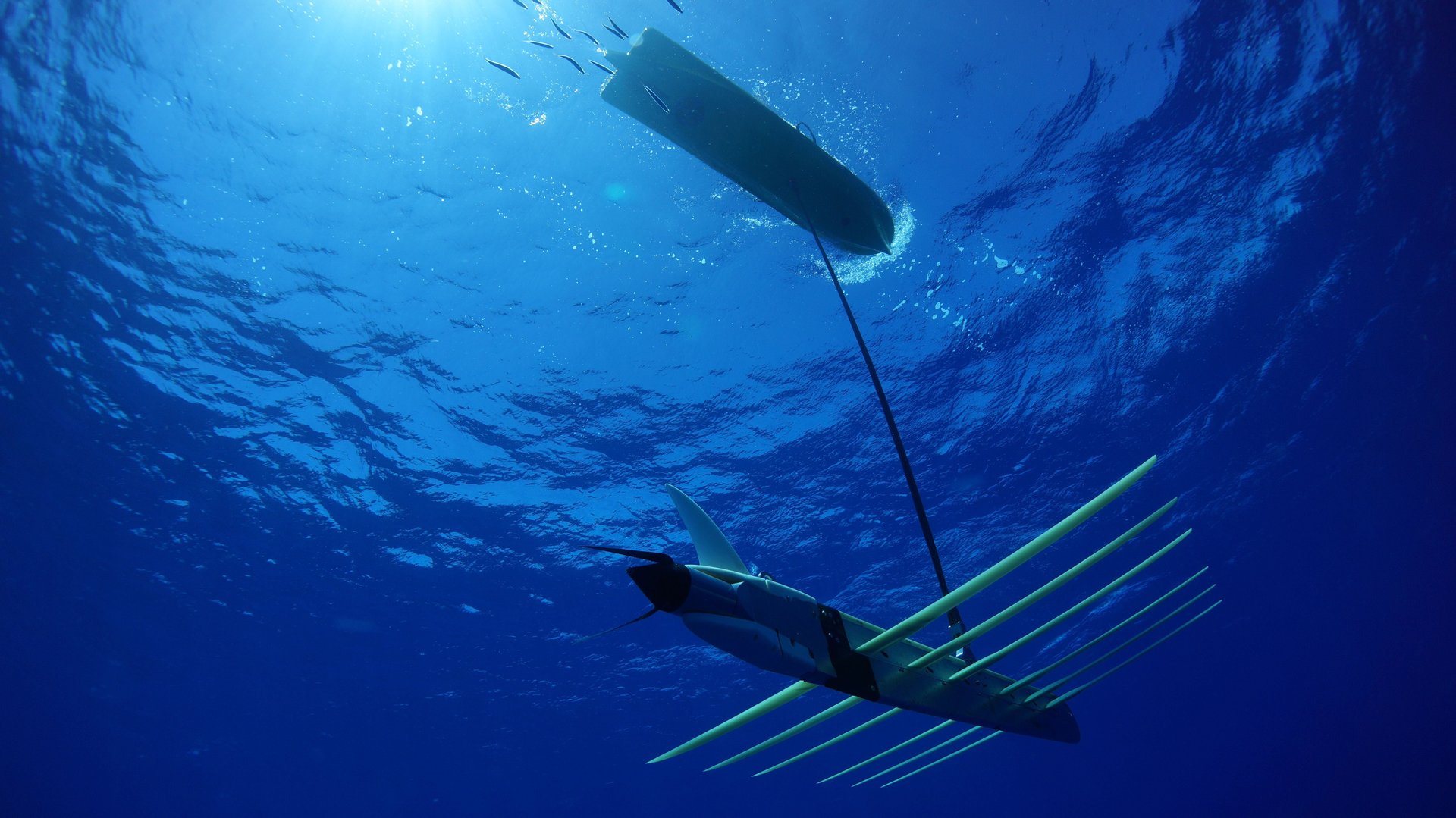

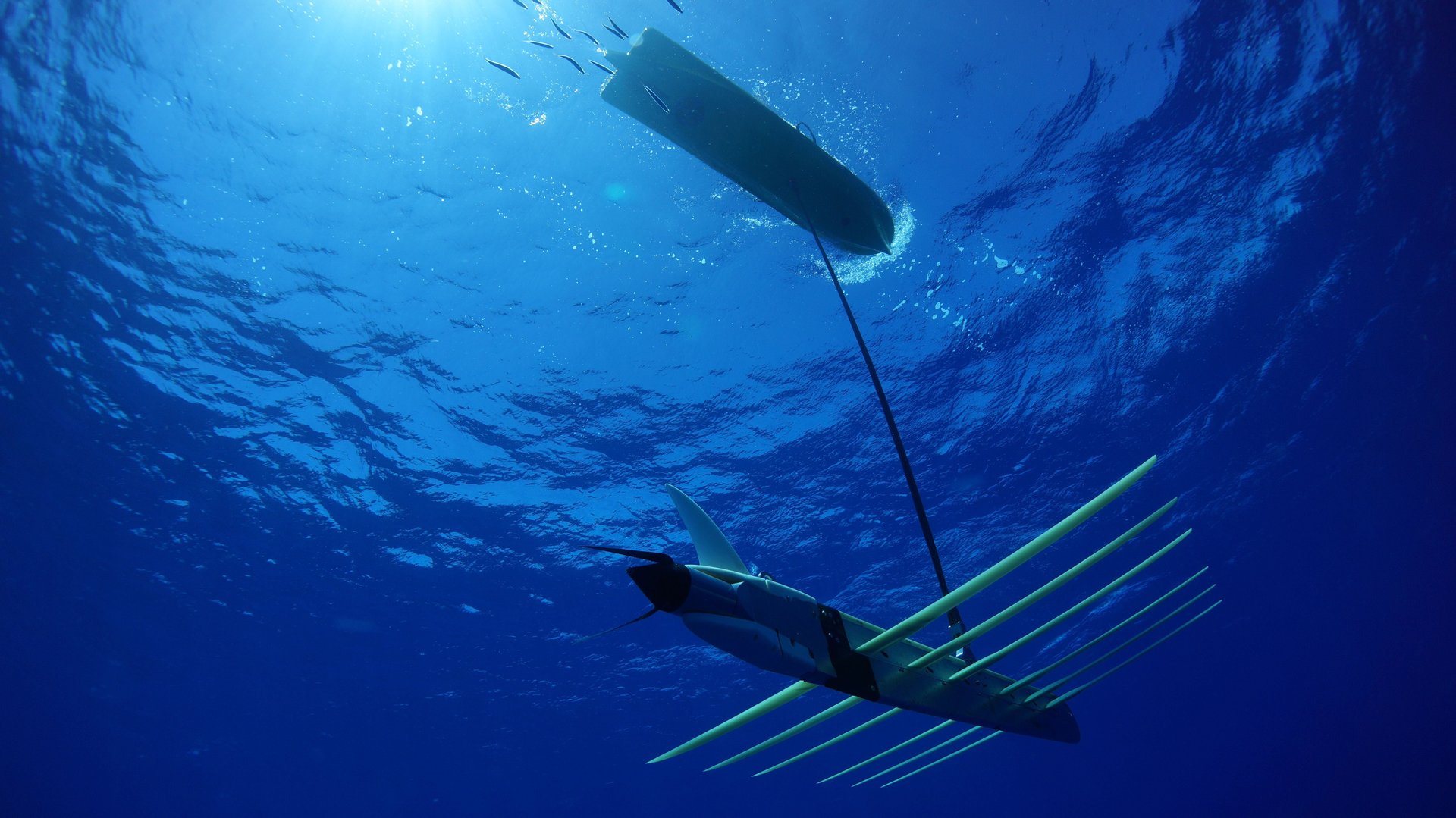

Called Wave Gliders, the surfboard-sized ‘bots made by Silicon Valley firm Liquid Robotics set out on a record-setting, 10,000-mile trans-Pacific crossing to Australia and Japan in November 2011. A year later two of the Wave Gliders arrived in Australia while the two others ran into problems and never reached their destination in Japan. Along the way the robots’ sensors collected terabytes of data on ocean conditions and Liquid Robotics sponsored a contest called the PacX Challenge for scientists to make best use of that information.

This week an independent scientific board named Villareal the winner, awarding him a $50,000 research grant from oil giant BP (irony noted) and putting Wave Gliders at his disposal for six months. Villareal studies diatom phytoplankton, the microscopic plant species that are critical to removing carbon from the atmosphere. Think of them as the Amazon jungles of the seas.

“When does this carbon removal occur, where does it occur, how long does it last and how much carbon are they sequestering are the questions we’re trying to answer,” Villareal told Quartz.

“At certain stages of their life history, they start forming these large masses like diatom dust bunnies,” he says. “The consequences are that at some stage in the diatom bloom these things turn into rocks that sink very fast. It’s a way for carbon to get to the bottom of the ocean and be sequestered without being eaten by fish.”

To study that phenomenon, Villareal and his research partner, Cara Wilson of the US government’s NOAA Fisheries service in California, need to be present during the brief time when deep ocean phytoplankton blooms occur. Easier said than done. Satellite images can pinpoint blooms and then one of those pricey research vessels must race to reach them before they disappear.

“Ship schedules are booked a year in advance and you have very little leeway,” says Villareal. “You only have a few days a year on the ship and you once get out there and the blooms can disappear.”

Wave gliders incur a fraction of the cost of a research vessel and can operate autonomously for a year or more at a time, propelling themselves through flapping fins that tap the power of waves while charging their instruments through solar panels. That promises to unleash a revolution in climate change ocean research, according to Villareal.

“I can send a Wave Glider out there to areas where we know conditions are right for blooms and just park it and wait for a bloom to occur,” he says. “You can’t do that with a research vessel.”

The robots are able to collect much more extensive data, which they beam through a satellite link to cloud servers. Graham Hine, Liquid Robotics’ senior vice president for product management, told Quartz that if that data show promising areas for further investigation, scientists can simply order a Wave Glider to return to a particular bloom.

“What we’re hoping is that the Pacific Crossing Challenge will inspire the scientific community to take advantage of this tool and use it for further study,” he says.