Shutting down the US government may be the smartest decision Republican hardliners have made all year

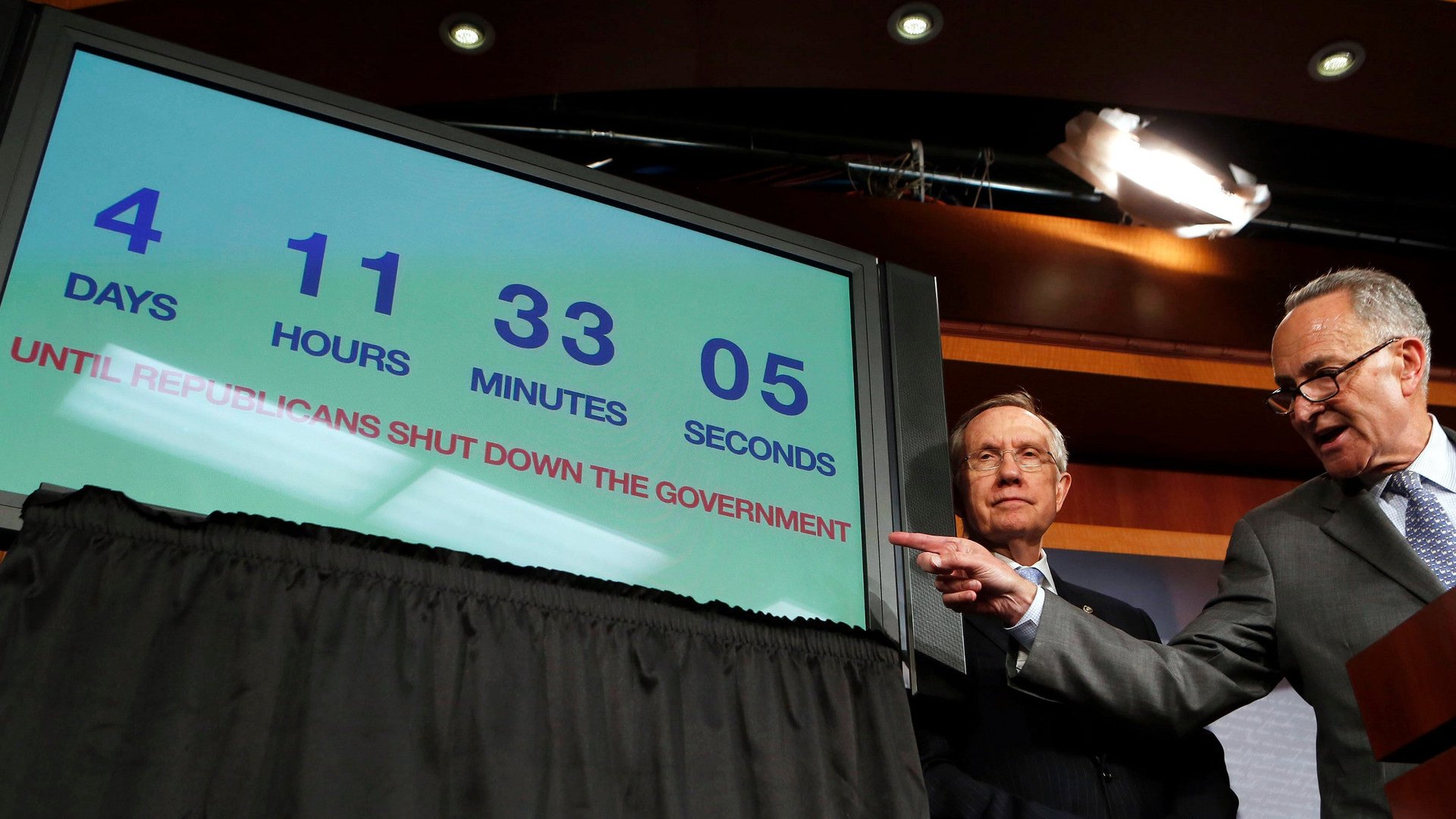

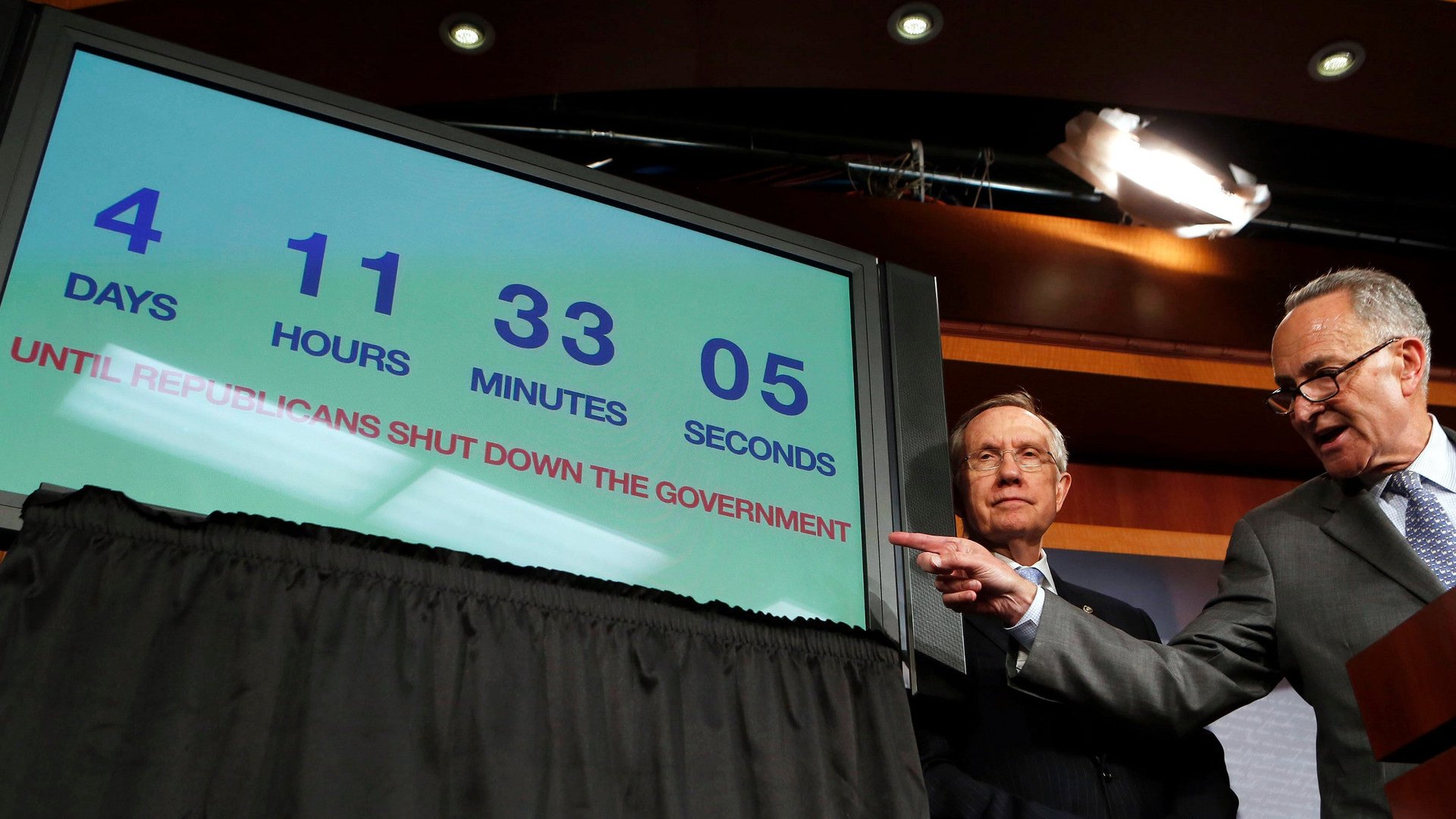

The US government is now more likely to shut down on Tuesday, October 1. And this is a good thing.

The US government is now more likely to shut down on Tuesday, October 1. And this is a good thing.

Yesterday John Boehner, the Republican speaker of the House, released a plan to avert the country’s collision with its debt ceiling on Oct. 17. His proposal: Agree to raise the debt limit for another year, in exchange for a laundry list of Republican demands that includes delaying the implementation of Obamacare for another year. His rationale: Doing that would allow Republican hard-liners to pass a spending bill to keep the government running past Monday—a bill they were refusing to pass unless Obamacare were stripped of funding. Yet those same hardliners killed his plan.

So why is this a good thing? Not because a government shutdown is a good thing or because the debt ceiling shouldn’t be raised (it should). It’s because doing the former might allow the US political system to find a way to do the latter.

Boehner’s debt ceiling plan amounted to a coup d’etat. His list of demands was the enactment of every Republican policy priority, debt-related or otherwise, that the other two elected branches of government haven’t taken up. However you feel about the specifics, it’s no way to run a government, especially when both parties in fact agree that the debt ceiling should go up.

But where they don’t agree, and need to, is on how the government should spend its money from now on. A government shut-down is the traditional venue for this kind of talk: You can’t agree on spending, so stop spending until you agree. It’s much less destructive, at least in the near term, than not raising the debt ceiling, which immediately becomes a crisis. If the US government needs a crisis to solve its problems, a shut-down is the better crisis.

In the last government shutdown, in late 1995 and early 1996, bond yields and the dollar fell precipitously as traders wondered how the Federal Reserve would react to the government’s indecision. But stocks, though volatile, kept moving upward. “I went in this morning with both hands full of money and was just buying everything I could,” a tech stock analyst told the AP in 1995.

However, that’s because the economy was stronger. At the time, the big economic question was whether the Fed would raise to fight inflation and bring down growth. Today a political crisis would have a larger effect.

So what if a shutdown happens? The challenge will still be to get a bill through the House. Democrats want a “clean” agreement (i.e., one that doesn’t defund Obamacare) to continue spending at current levels; Republicans who control the chamber may not bring one to the floor, and want additional sweeteners to attract conservative votes. Immediate spending cuts will be difficult to implement, since even the Republican-dominated House has struggled to pass spending bills under current spending levels—had Congress done so, this little crisis wouldn’t be happening.

The Obama administration is willing to talk about a budget deal—even one that the median Democrat won’t like—that doesn’t dismantle its signature health care reform. But on the debt ceiling, it won’t budge.

Perhaps most important, though: A few days of dysfunction next week could help ramp up outside pressure on Congress as the rest of the country—and world markets—realize that US lawmakers aren’t just capable of reaching the brink, but of stepping over it too.