Why we shouldn’t write off cursive

Cursive is an art. It’s woven into the very fabric of the US constitution. Yet, everywhere we look, it’s literally being written out of existence. Like a sandcastle built at the edge of the sea, with each crashing wave, the strokes of cursive are slowly fading away.

Cursive is an art. It’s woven into the very fabric of the US constitution. Yet, everywhere we look, it’s literally being written out of existence. Like a sandcastle built at the edge of the sea, with each crashing wave, the strokes of cursive are slowly fading away.

Once at the very heart of public school education, cursive is aggressively being replaced by computer classes. As of today, 45 states have adopted the Common Core State Standards for English, which omits cursive from required curricula in schools today.

Instead of learning the basics of cursive handwriting, children are increasingly being introduced to the nuances of the keyboard. There’s absolutely no denying the importance that computers play in our world. You’re reading this in print, on a computer, tablet, or mobile device.

Yet, we wonder, how widespread is this phenomenon? One of the strongest current indicators is, perhaps surprisingly, the SAT exam. When handwritten essays were introduced in 2006, “just 15 percent of the almost 1.5 million students wrote their answers in cursive.” The rest wrote in print. While cursive is currently on the chopping block, is it too far of a stretch to think that print might soon share the same fate?

Opponents of script argue that needing to read and write in cursive is no longer relevant in an increasingly digital society. Some believe that cursive is essentially archaic, the importance of which is relegated only to checks, signatures, and the occasional love letter. They believe instructional time is better devoted to other classroom subjects that are included on standardized tests, and cursive is not necessary for academic achievement. After all, they say, we have computers and speech dictation machines. It’s even been suggested that cursive should be moved to art classes, where it could be more appropriately taught. The quill, and the speed with which cursive allowed the author to express his thoughts, is out of date. The message is clear: cursive just isn’t practical.

On the other side of the equation, cursive advocates and handwriting experts suggest that these reasons miss the point entirely. Saving cursive isn’t about rejecting technology or trying to preserve our history—let alone any perceived societal advancement. (Yes, the arguments get that entrenched, that fast.) Instead, they believe that the importance of cursive is a matter of science, and what’s best for teaching our children.

Rapidly, the pedagogical reasons start to fly, including ease of use, letter recognition, increased brain activation, higher academic performance, and greater coherence and reading comprehension. Of course, they have the MRIs to back it up.

Needless to say, both sides soon run out of fingers and points and we’re quickly left in the quandary by which we started: does cursive really matter? These conversations are reminiscent of the bombastic politics and grand overtures of the great Soviet-American space race. It’s a myth that Americans spent millions developing a pressurized space pen, while the Soviets merely took a pencil. But we wonder whether the first words in space were written in cursive or print. (The pencil turned out to be a highly combustible object, not advisable to carry into space.)

We wonder, however, if, amidst the-back-and-forth, an important point doesn’t get lost, carried out to sea with the perfectly crafted, three-story sandcastle, namely, the meaning that a personalized, handwritten message can send. Not just the aesthetics, but the expression of thought. There’s something to be said for reading into those jagged, curvaceous edges, interpreting the tear-soaked, bleeding splotches or following those clean, decisive strokes just to see where they lead.

Here’s one of our favorite stories:

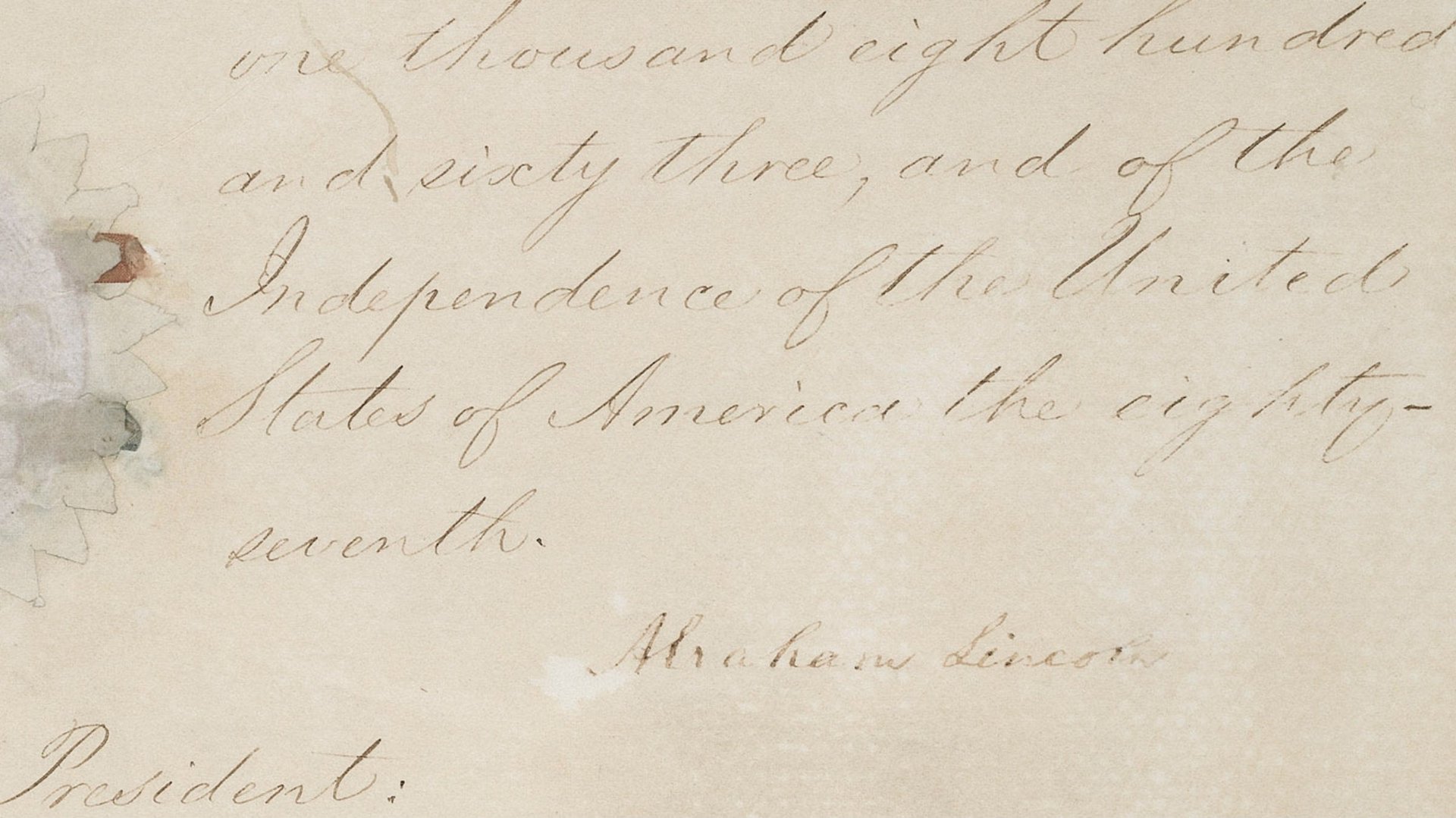

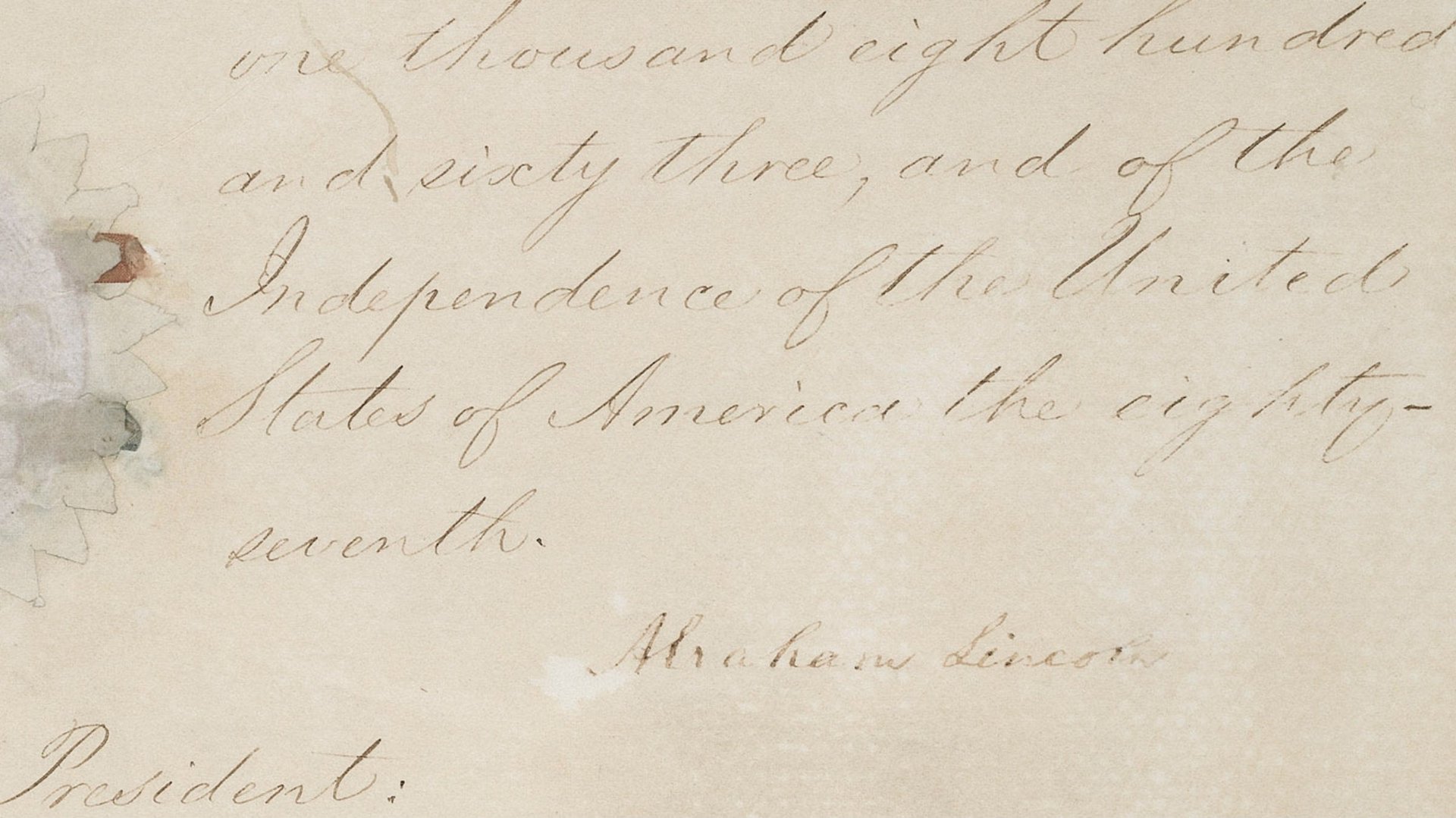

In 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, Abraham Lincoln said, “I believe in this measure my fondest hopes will be realized.” But, as historian Doris Kearns Goodwin explains, in her excellent TED talk, “as he [Abraham Lincoln] was about to put his signature on the proclamation, his own hand was numb and shaking because he had shaken a thousand hands that morning at a New Years reception. So he put the pen down and said, ‘If ever my soul were in an act it is in this act, but if I sign with a shaking hand, posterity will say, he hesitated.’ So he waited until he could take up the pen and sign with a bold and clear hand.”

There’s a reason Lincoln waited to sign his name. It wasn’t just about the act of writing itself. It was about the subtleties of his signature, the strength of his hand, and the fortitude and resolve that generations would discern, in that single, sweeping script known as Abraham Lincoln. Obviously, he felt his character would be reflected, not only in his words and acts, but also in the stroke of his pen. In a very meaningful way, the debate between cursive and print, or keyboards and handwriting, is entirely up to us: what type of mark do we want to leave?