For China’s young, seeing poorly is the norm—a little more play could help

This April saw China’s economic growth exceed already lofty expectations, reporting 6.8 percent growth in the first quarter of the year, fueled by seemingly insatiable consumer demand. And this May, as business giant Michael Bloomberg announced the launch of his New Economy Forum—a China-focused Davos rival—all signs point to the oncoming, inevitable shift that will install China as the globe’s economic center of gravity.

This April saw China’s economic growth exceed already lofty expectations, reporting 6.8 percent growth in the first quarter of the year, fueled by seemingly insatiable consumer demand. And this May, as business giant Michael Bloomberg announced the launch of his New Economy Forum—a China-focused Davos rival—all signs point to the oncoming, inevitable shift that will install China as the globe’s economic center of gravity.

And yet, behind the headlines lies a health issue that threatens that future. Simply put: Today, half of China’s 1.4 billion citizens can’t see properly.

China’s crisis of shortsightedness

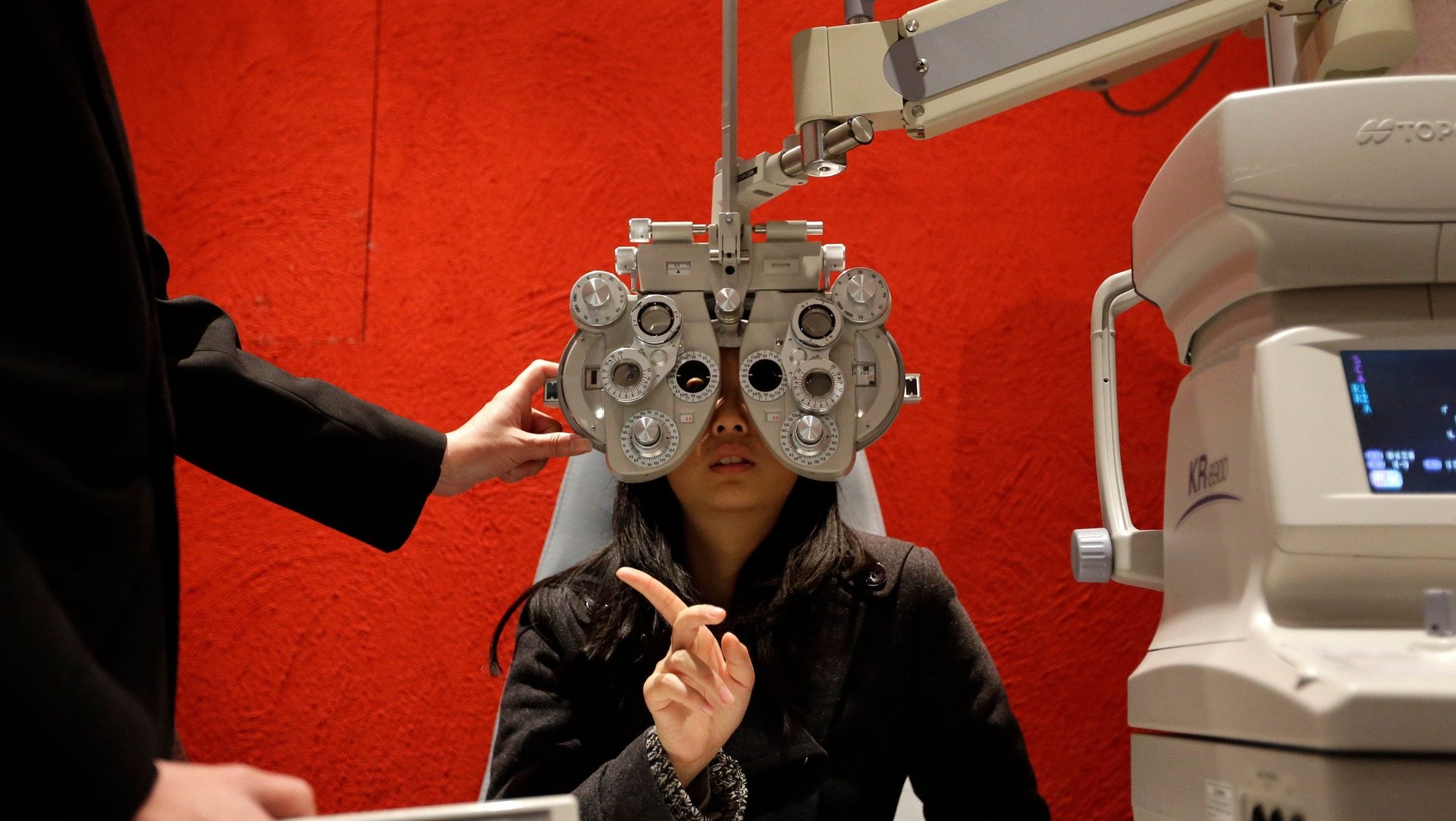

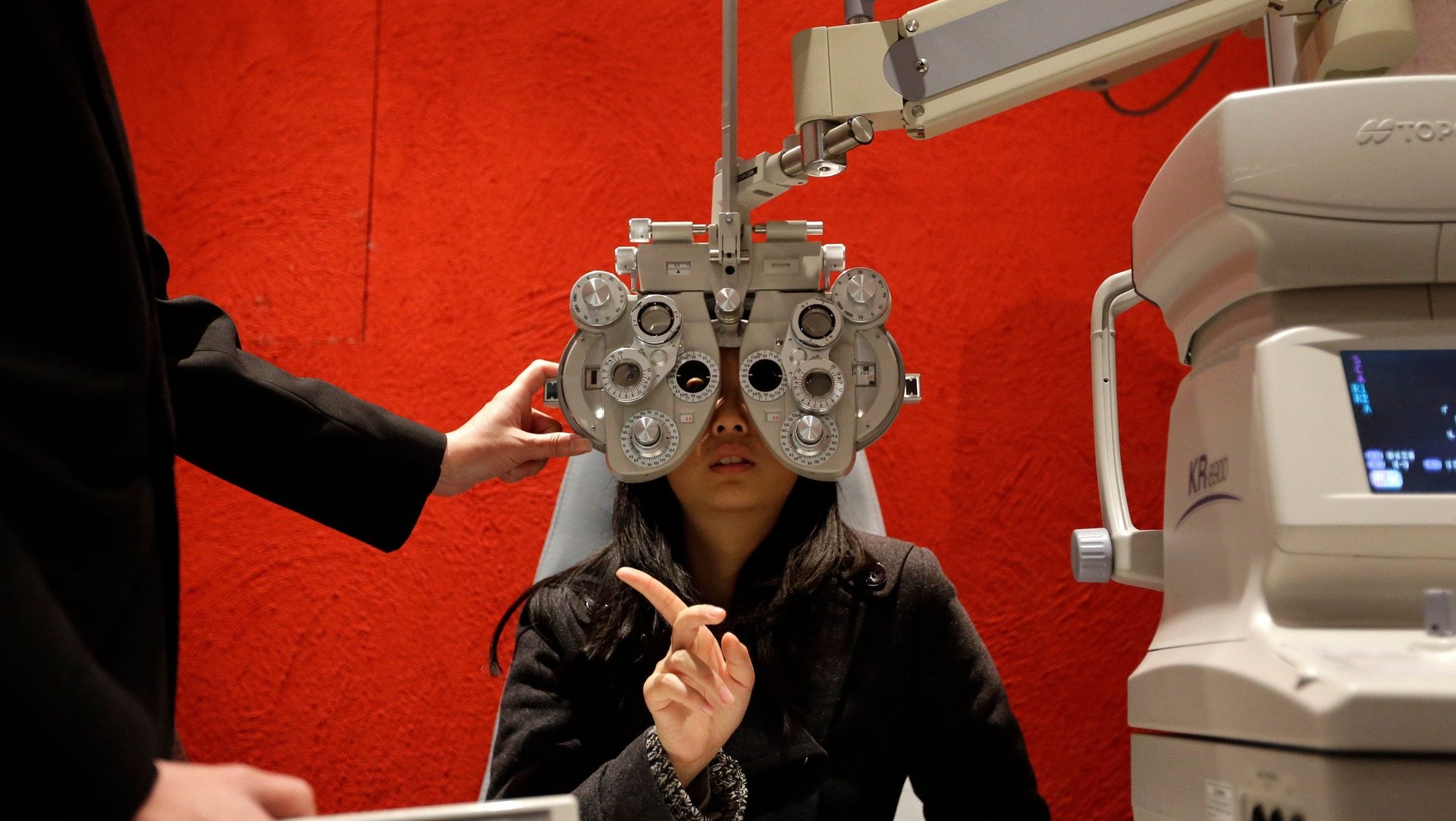

With an estimated 720 million people affected, China has the largest number of people with uncorrected poor vision in the world—a number on track to explode in the coming decade.

It’s estimated (pdf, p. 18) that between 10 and 20 per cent of children start school already short-sighted, a number that grows to 50 percent for secondary school children and reaches 90 percent for university students.

Experts at Shanghai Eye Disease Prevention and Treatment Centre have highlighted that 20 per cent of China’s young people actually have high myopia (-8 points)—roughly five times the global average—putting up to half of them at risk of eventual blindness.

Within the next 30 years, the center for Myopia Research at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University estimates that more than 80 per cent of the entire adult population of China will be short-sighted.

As rates of poor vision threaten to reach epidemic proportion, it’s not just the medical experts who are drawing attention to this issue. From leading charities to the government itself, groups across the country are increasingly recognizing the threat current rates of poor vision pose to education delivery, productivity and economic growth.

As China marks its National Eye Care Day this week (June 6)—two years into a five-year plan to improve vision across the country—many might ask why faster progress isn’t being made.

The simple solutions

Around the world today there are 2.5 billion people who suffer from poor vision, who have no access to treatment.

Estimates from data analysis firm Access Economics (pdf, p. 8) suggest that current rates of poor vision cost the global economy upwards of $3 trillion every year in lost productivity, informal and formal health care and road and domestic accidents alone.

There is, however, a simple solution. As we outline in “Clearly: The China Report,”published last week, only 10 per cent of people with poor vision need surgery and special medication to deal with complex eye diseases. The other 90 per cent need little more than a pair of glasses to live their lives independently and productively—an invention that’s been around for 700 years.

In China and beyond, the principal challenge lies in delivering that simple solution to the people who need it.

I’ve spent 13 years working to tackle this chronically unaddressed disability. In much of the developing world, the primary barrier to tackling poor vision is diagnosis: from Burundi to Bangladesh we face a vast shortage of trained optometrists and ophthalmologists. Traditionally, the second major barrier is the availability and distribution of glasses—in countries that often lack infrastructure to manufacture or import and distribute medical products.

However, in this advanced economy, both of those traditional barriers are seemingly already cleared.

China is currently home to 28,000 ophthalmologists—five times more than the World Health Organisation’s guidelines and is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of glasses.

Yet, while the challenge faced in China is entirely distinct from its African or South Asian counterparts, there are lessons to be learnt from one of them.

Sunlight and social change

Over the last decade, researchers have invested heavily in understanding why China is disproportionately affected by severe and often untreated visual impairment, and the principal reasons appear to be social.

A study that took place in 2012 with 15,000 children in the Beijing area found that poor sight was closely linked with more time spent studying, reading and using electronic devices—and crucially to spending significantly less time outdoors. Sunlight plays a vital role in the development and health of the eye—but children in China are spending an average of only one hour a day outside, compared to Australian counterparts who spend up to four hours each day away from their computers.

Secondarily, whilst China’s highly-educated ophthalmologists abound, they are overwhelmingly based in urban centers, unable to reach 42 per cent of the population based in rural areas.

Another significant problem encountered by China’s government leaders, and nonprofits working to deliver primary eye care has been a long and deeply-held belief that glasses can be harmful to your sight.

The challenge facing government, health workers and NGOs in tackling this growing problem therefore lie in tackling ingrained social structures: from societal and familial pressure on young children to outperform at school to generational skepticism of western medicine.

Play a little bit more

Landmark research from Sun Yat-sen University showed that increasing the amount of time children spent outdoors per day by as little as 40 minutes, produced a 23 per cent reduction in shortsightedness. A change of this kind could be integrated directly into China’s education system and have a transformative effect.

It can be done: just over five years ago we set out on a project to make Rwanda the first developing country in the world to deliver universal eye care services.

Everyone told us it wouldn’t be possible—but by working closely with the Rwandan Health Ministry, we designed a simple three-day training course that went on to equip 2,700 local nurses with the tools to diagnose basic visual impairments and conditions in villages around the country.

Our outreach centers worked hard in local communities, from Kigali to rural towns, to dispel myths and drive demand and understanding of glasses. To date, the program has delivered 2.5 million eye screenings and 1.2 million basic treatments—as of December last year, every citizen in Rwanda has access to primary eye care.

For a nation on track to become the globe’s biggest economic power, China certainly has the means and motivation to solve a threat that could dim its bright future.