The class inversion: how American politics turned upside down

Listening to Barack Obama and Mitt Romney campaign over the last few months, it’s easy to assume that the US presidential election fits into the familiar class alignment of politics almost everywhere else around the globe, with the liberal party rallying the less fortunate while the conservative party relies on the wealthiest.

Listening to Barack Obama and Mitt Romney campaign over the last few months, it’s easy to assume that the US presidential election fits into the familiar class alignment of politics almost everywhere else around the globe, with the liberal party rallying the less fortunate while the conservative party relies on the wealthiest.

That pattern is indeed somewhat visible in the campaign financing: Although Obama and Democrats have plenty of wealthy supporters, Romney is benefiting from a remarkable outpouring of dollars from those at the very top. But when it comes to the votes the two men are pursuing, the story is actually reversed. If Obama survives, it will likely be the white upper middle-class that saves him (with one exception we’ll return to later.) And if Romney wins, he will likely need to thank voters from the white working class, many of them of modest means.

This counterintuitive dynamic is the result of one of the most powerful trends to reshape American politics over the past half-century: a “class inversion” that has scrambled each party’s core coalition of support.

From Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal during the Depression through the 1960s, American politics followed the tracks familiar in most of the world. The party of the left was the party primarily of people who worked with their hands: minorities and blue-collar white voters, mostly of limited incomes. The party on the right represented those who wore a jacket to work: professionals, managers, executives, small business owners.

One measure of this division came in the exhaustive polls conducted after every presidential election by the University of Michigan. In those surveys, Democratic presidential nominees from Adlai Stevenson in the 1950s to Jimmy Carter in the 1970s routinely ran at least 13 percentage points better among white voters without a college education than those with at least a four-year degree.

But this electoral order began to shatter in the 1960s. Republicans punched the first hole in the wall. They made inroads among working-class whites, initially around racially tinged subjects like civil rights and bussing designed to integrate urban schools, later around social issues like abortion, gun control, and the role of women. “The movements of the 1960s, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay movement, the anti-war movement did send shockwaves through the white working class that made them less sympathetic to a Democratic party that seemed to be coddling these kind of behaviors,” says Ruy Teixeira, a Democratic analyst who has written extensively on the shifting nature of the two parties’ coalitions.

The second shoe dropped in the 1970s and 1980s, as a generation-long slowdown in the growth of living standards for workers without college education made them more sympathetic to Republican arguments that government wasted too many of their tax dollars, particularly by redistributing them to the “undeserving” poor. “The economic world they grew up in and loved, that the Democratic Party and the government were a part of, fell apart,” said Teixeira. “And that convinced them that government, which was still handing out checks to people, was handing them out to people who didn’t deserve them.”

Especially after Democrats grew more skeptical of military intervention following Vietnam, foreign policy reinforced the change: blue-collar whites proved a responsive audience to conservative peace-through-strength arguments. The decline of unions, who reliably steered their members to the Democratic Party, added another brick to the load.

The result was an enormous realignment of working class whites toward the Republicans that reached an apex in 1984 when Ronald Reagan won nearly one-fourth of self-identified Democrats. Many of these “Reagan Democrats” were blue-collar whites who had grown up in a house with a picture of Franklin Roosevelt and probably union leader Walter Reuther on the mantle.

Those voters have never really looked back since. Even in 2008, during the worst economic downturn since the Depression, John McCain won nearly three-fifths of white voters without a college education. Racial antagonism toward the first African-American president contributed to that result, but the overwhelming impetus was this long-term estrangement between Democrats and the white workers that once anchored their coalition.

With much less attention, the converse trend began during the 1980s: the Republican power base of college-educated white voters, especially women, began to move to the Democrats. These voters tended toward the liberal position on the same social issues (like abortion, gun control and gay rights) that drove blue-collar whites toward the Republicans and usually viewed diplomacy and alliance, rather than unilateral force, as the best way to safeguard American interests around the globe. Once Bill Clinton identified the Democrats with a more fiscally-responsible agenda, this process rapidly accelerated in the 1990s, and Democrats flipped into their column a succession of comfortable suburbs outside the South—and with them previously Republican-leaning mega-states like California, Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The result was the class inversion. In contrast with the Democratic nominees from Stevenson through Carter, Clinton each time ran as well among college-educated whites as those without degrees. Then in 2000, Al Gore ran four points better among college than non-college whites; in 2004, John Kerry ran six points better. In 2008, Obama ran seven points better, winning only 40% of non-college whites but 47% of those with degrees, including a 52% majority of college-educated white women. (That marked the fourth time in the previous five elections Democratic nominees have won those upscale women.)

If Obama wins a second term, the class inversion in 2012 will almost certainly be even wider than it was in 2008. At a national level, most polls show Obama struggling to match the meager 40% he won among non-college whites last time; a Quinnipiac University Poll this week put him at just 36%. But, at least before Obama’s disastrous debate performance on Oct. 3, most surveys showed him nearing, or even exceeding, his 2008 showing among college-educated whites. (Quinnipiac put him at fully 50% with those whites.) While he’s suffered some erosion with upscale men (who respond well to Republican anti-government arguments) almost all surveys show him equaling or exceeding his 2008 number with college-educated women, who recoiled from the staunchly conservative tone on social issues during the Republican nominating primaries.

All of this has produced a complex alignment in American politics that confounds easy stereotypes. Both parties now rely on coalitions of voters that cut across socioeconomic classes. The Democratic base is primarily minority voters (most of them below the median income) and white-collar whites—particularly professionals with post-graduate degrees, like consultants, teachers and other workers in the “creative class.” Republicans depend heavily on working-class whites but maintain the edge among more conventionally business-oriented upscale whites who own their own firms or work for big companies.

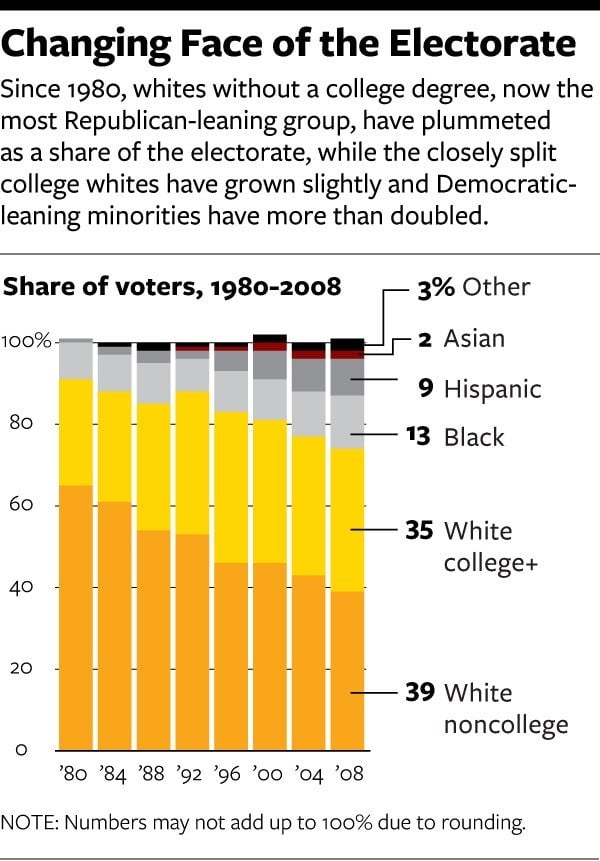

As I wrote last week, this shift in party loyalties coincides with a steady demographic trend (see chart): The non-college-educated whites who have become a large part of the Republican base are declining as a share of voters, while the minorities who support the Democrats are growing and so too, more slowly, are the educated whites who are moving more pro-Democrat. Combined, these two trends augur ill for the Republican party in its current incarnation.

These national patterns are evident as well in most of the key battleground states. The one exception works to Obama’s advantage. Recent state polling in the behemoth Midwestern battlegrounds of Ohio, Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan show Obama running much better than nationally among working-class white women, who have responded to his campaign’s advertising portraying Romney as an indifferent plutocrat. In an election once again dividing the country almost exactly in half, Obama will need to mobilize just enough of both the old and new Democratic coalitions to survive.