What the US can learn from Switzerland’s successful approach to vocational education

The US consistently underperforms on international academic benchmarks compared to other developed countries—a reality that education secretary Betsy DeVos seems intent on changing.

The US consistently underperforms on international academic benchmarks compared to other developed countries—a reality that education secretary Betsy DeVos seems intent on changing.

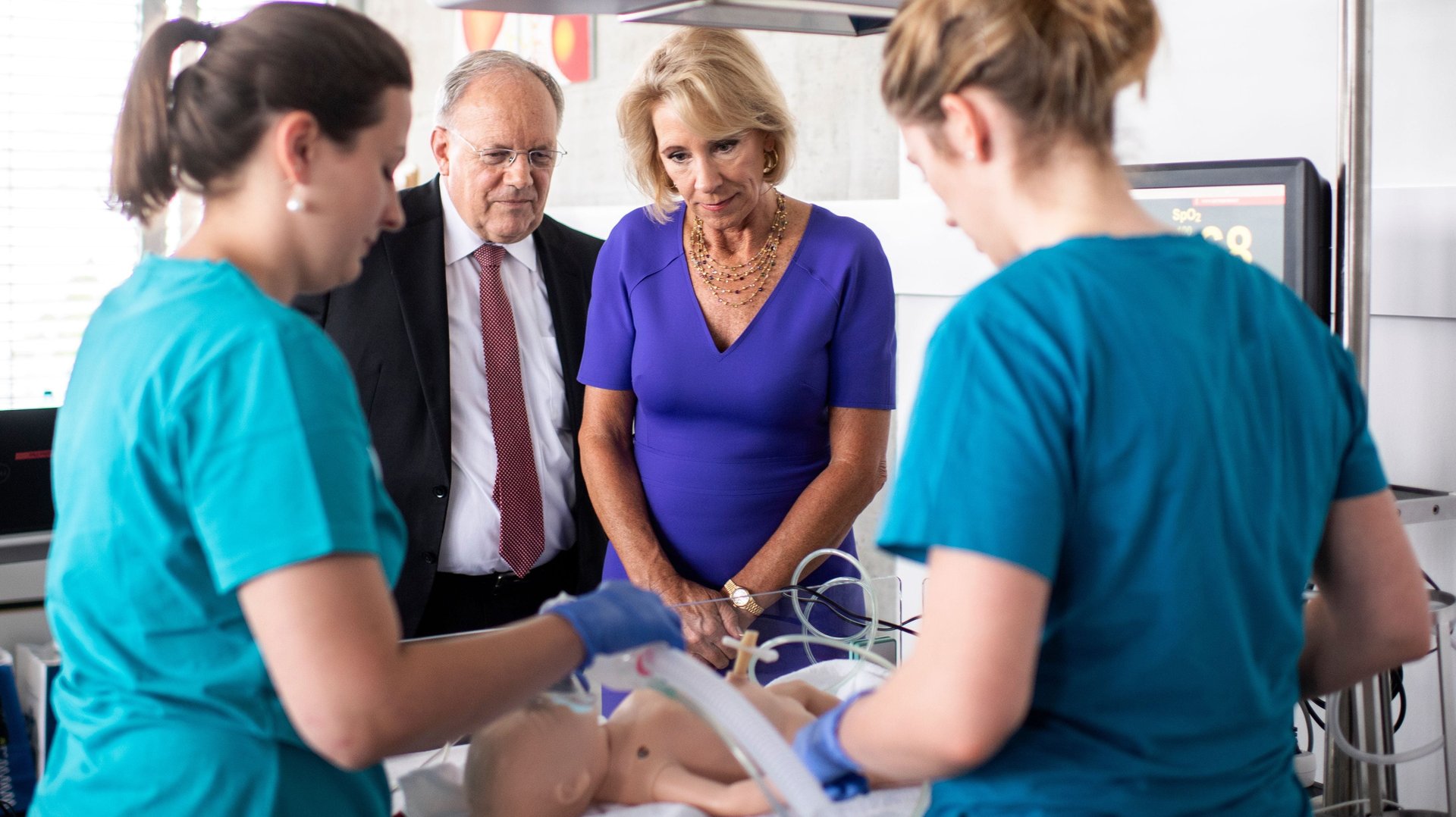

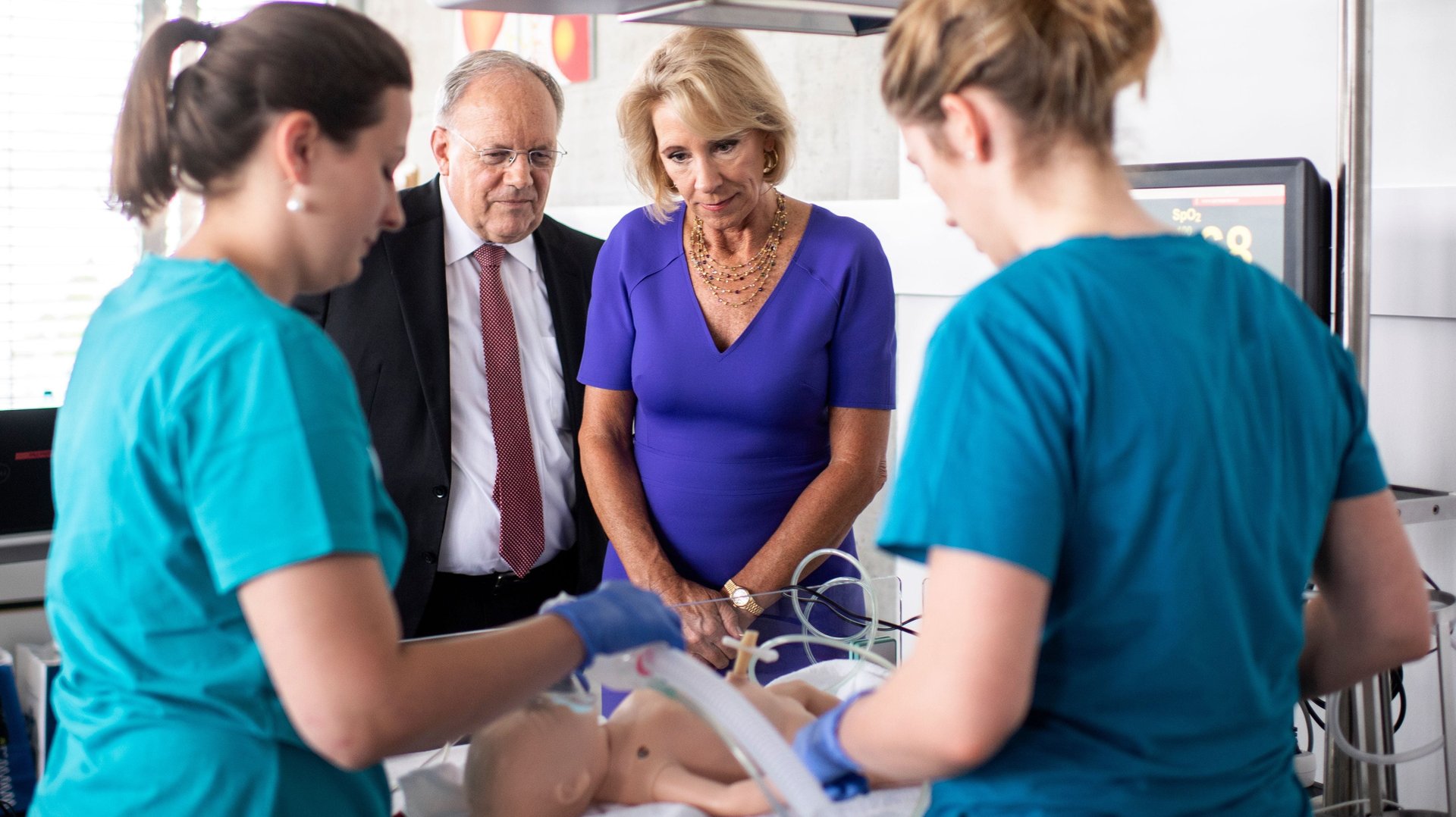

DeVos is on a 10-day, multi-stop visit to Europe to learn about apprenticeship programs, vocational schools, and the European K-12 education system. Billed as a “learning tour,” DeVos’s visit, which ends Friday, will take her to Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands—three countries that have something to teach the US about the value of vocational training for 21st-century education systems.

DeVos is particularly looking into how the Swiss vocational education system powers the country’s economy, and whether its success can be replicated. The US could benefit from more technical education in several key ways. First, for years, American manufacturers have been reporting a “skills gap” between the talent they need to keep growing their businesses and what’s available on the job market. Effective job training programs could help narrow that skills gap tremendously, putting people back to work and filling vacancies within American businesses. Second, college and technical expertise in areas like science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) is one of the surest routes to a high-paying job today. And third, apprenticeships and trade schools can provide career training and intellectual development for economically disadvantaged young adults, or kids with disabilities, or those who feel like college isn’t for them. Instead of “checking out,” these kids might then go on to learn high-paying STEM skills and fill crucial gaps in the labor market.

What is vocational training?

Vocational educational programs train students in the practical and theoretical skills they will need for future employment. This type of training can take different forms, including technical schools and internships, but apprenticeships are the most common. Apprentices receive on-the-job experience in firms for most of the week, which is supplemented by theoretical training in a classroom setting.

Switzerland is one of several European countries with a so-called “dual” vocational education and training (VET) system, in which students who participate in these programs, either instead of or before going to university, combine learning in school with learning in workplace settings. In Switzerland, as opposed to the US, a majority of young people (close to 70%) go through VET, which trains them in a broad range of professions. In the US, in 2014, there were only about 410,000 active apprentices registered with the federal government.

About 30% of Swiss companies host 16- to 19-year-old apprentices who “do everything an entry level employee would do, albeit under the wings of credentialed trainers within the company,” write (pdf) Nancy Hoffman and Robert Schwartz in Gold Standard: The Swiss Vocational Education and Training System. These apprentices’ learning is highly personalized based on their interests, and they are paid a living wage.

In the US, apprenticeships are most commonly thought of as training for blue collar jobs like welding and carpentry. But in Switzerland, apprenticeships and vocational education programs train both welders and lawyers alike. In her keynote speech to the International Congress on Vocational & Professional Training on June 7, secretary DeVos confessed to having been surprised to find out that both the CEO of UBS, Sergio Ermotti, and Lukas Gähwiler, the chairman of UBS Switzerland, started their careers as apprentices. As she stated, “That’s not commonplace in America, but perhaps it should be.”

Does vocational training work?

There is mixed evidence on the success of vocational training. Generally speaking, both vocational and apprenticeship training can play an important role in reducing youth unemployment and increasing workforce productivity. As Hoffman and Schwartz note, “VET did not build the Swiss economic engine; it serves and contributes to it.”

But recent research points to a harmful side effect that could come with significantly expanding career and technical training in the United States. While students may benefit from vocational training early in their careers, they could be more vulnerable later in life, as the economy changes and they lack the general skills necessary to adapt. In fact, “by their late forties, those who went through a general education program have higher employment rates,” writes Matt Barnum in The Atlantic.

Even among experts, there doesn’t seem to be widespread agreement as to what works best. Some studies have found that vocational training is more successful in terms of skills, employment status, and earning than apprenticeships. Yet another study disagrees, and shows that “apprenticeship training improves the early labor market attachment relative to vocational schooling.”

In Switzerland, the VET system is widely recognized to be a contributing factor in the country’s strong economy and virtually nonexistent unemployment rate. The system supports young adults’ transition from school into the labor market, as well as from childhood into adulthood. “If it is possible,” write Hoffman and Schwartz, ”for an education system both to serve successfully the needs of adolescents and support their transition into adulthood and the needs of employers in a highly competitive economy, then Switzerland arguably does a better job than any other developed country. “

But the US is not Switzerland. Barriers to the implementation of more vocational training programs that do not exist in the latter, exist in the former.

Why hasn’t the US implemented more vocational training programs?

Vocational training has been declining in the US since the 1980s, and separate vocational tracks have been eliminated in most high schools. That’s because, in the 1980s, policymakers and educators became concerned that the academic performance of American students was falling compared to other developed countries, and correspondingly expanded the number of academic courses and schools preparing kids for four-year colleges, at the expense of vocational tracks. But there’s broad support across the US political spectrum for bringing this type of training back, and helping more students learn career-specific skills in high school. In fact, speaking at Gateway Technical College in 2017, US president Donald Trump described vocational education as “the way of the future,” and pledged to create 5 million new apprenticeships over the next five years, an almost 10-fold increase from its current count.

As of now, the Trump administration has appropriated roughly the same amount of money to apprenticeships as the Obama administration.

Funding isn’t the only roadblock to implementation. Unlike in Switzerland, where work-based learning has been enshrined in laws and the Constitution for more than a century, vocational training is not as engrained in the American educational system or labor market, and businesses are reluctant to make the long-term investment required to turn the training of apprentices into a higher bottom line, especially when they can’t be sure those workers will then stay in the company.

Swiss companies, in contrast, not only host the nation’s apprentices, but are also involved in setting the national standards of skills the apprentices need to train for a specific profession. According to Education Week, in Switzerland, ”professional associations also craft the curricula that guide on-the-job training and the assessments that apprentices take halfway through and at the end of their three- or four-year apprenticeships.”

Another obstacle to implementation in the US is a concern that the vocational track might close doors for young people who change their minds about their careers midway through completing an apprenticeship, or for those who later decide to go to college. That’s because, unlike a generalized college education, vocational education trains kids in a specific set of skills that are difficult to transfer. The kids who do train in more generalized systems tend to be wealthier, potentially giving them the upper hand on the labor market. Even in the Swiss system, a country of 8 million people, class divides exist between those who go through the VET system and those who take the university route instead. How can we make sure that doesn’t happen in a country of more than 327 million?

Hopefully, secretary DeVos’s European tour will lead to answers to this and other questions. Those answers are badly needed to develop quality vocational training for the 21st century.

This article has been updated to correct the job title of Lukas Gähwiler. He is the chairman of UBS Switzerland, not the chairman of UBS.