Private equity funds aren’t nearly as attractive as they think they are

Private equity firms are delusional. A record number—nearly 2,000 of them—are currently out on the road seeking more than $700 billion in fresh funds, according to new statistics from data provider Preqin (pdf).

Private equity firms are delusional. A record number—nearly 2,000 of them—are currently out on the road seeking more than $700 billion in fresh funds, according to new statistics from data provider Preqin (pdf).

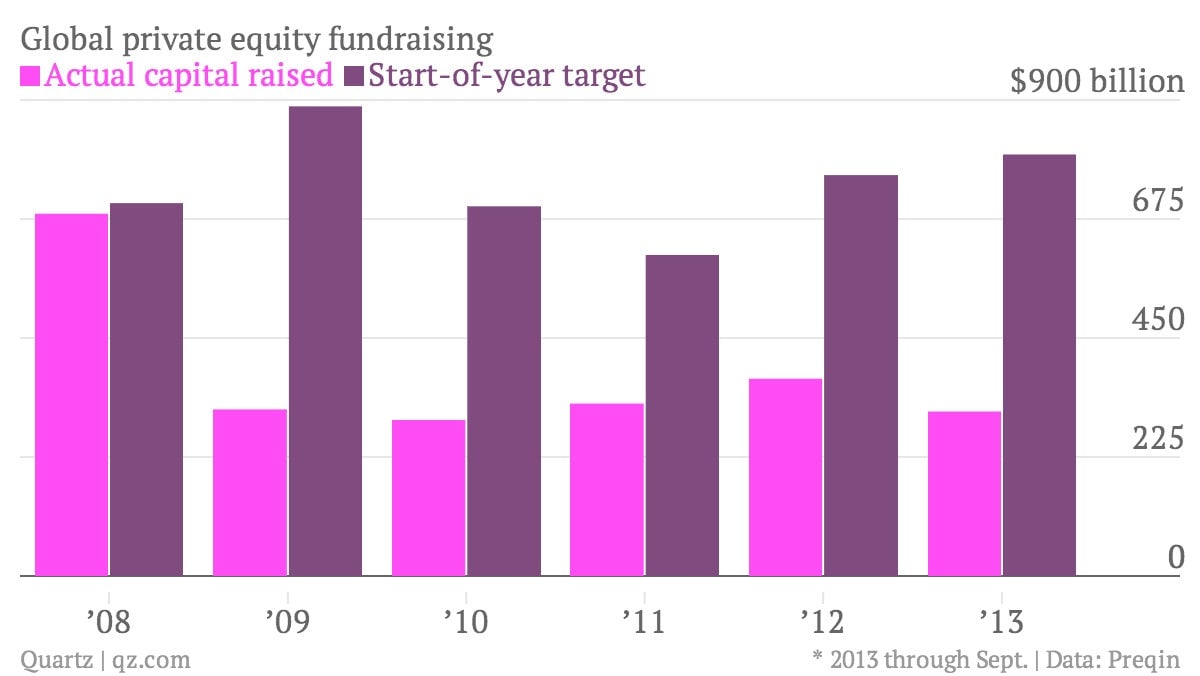

Considering that PE firms haven’t raised anywhere near their targets since the financial crisis, this is a triumph of hope over experience. Although fundraising year-to-date is up 20% versus the same period in 2012, the industry is still a long way from its glory days in the mid-2000s, when credit was cheap and plentiful.

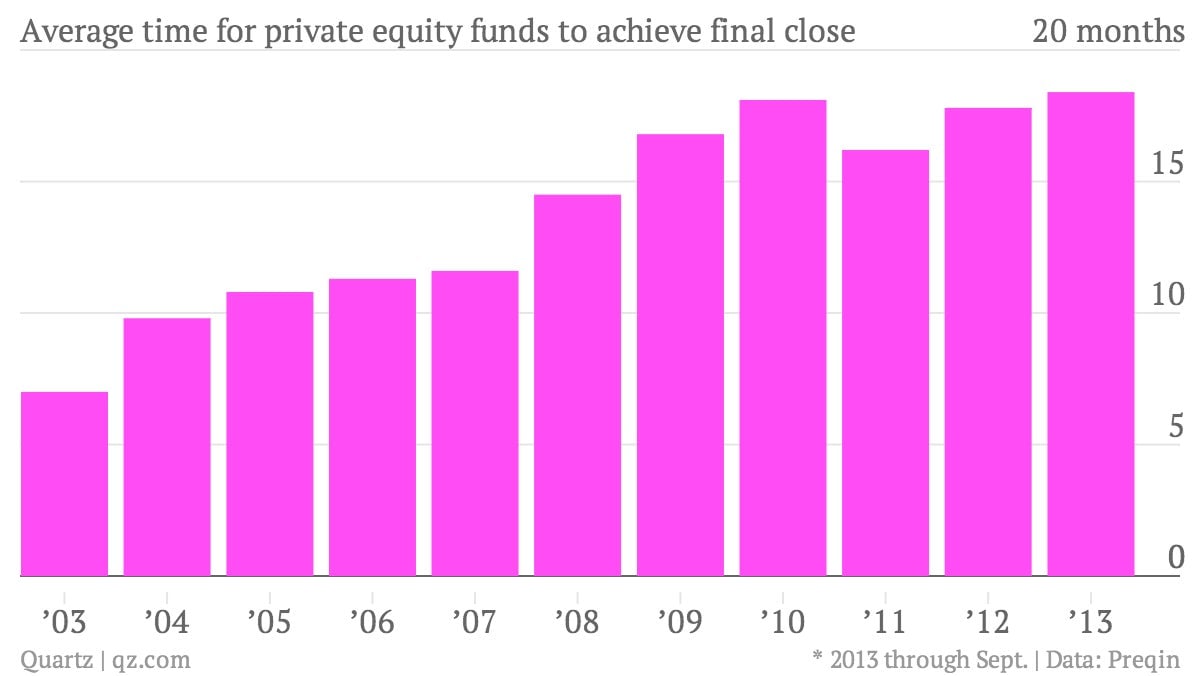

The size of the average buyout fund that closed a fundraising round in the third quarter was $996 million, down sharply from $1.8 billion in the previous quarter. So although the industry as a whole is growing again, the size of the average player is shrinking. And raising funds takes more time than ever before, despite the more modest sums involved. In the first nine months of this year, it took the average private equity firm 18.5 months, a record high, to close its latest fundraising round. See the lengthening time frame in the chart below:

What gives? Private equity firms are sitting on some $1 trillion in “dry powder,” or uninvested capital from previous fundraising rounds. Like cash-heavy companies in the corporate world, the firms are hoarding more cash, partly because they’re having trouble finding worthy investments amid economic uncertainty and a dearth of cheap debt that helped juice returns in the pre-crisis days. It’s also taking longer for PE firms to exit their investments, as M&A and IPO activity remains choppy. Thus, many PE investors are locked into funds that sit on a large share of their cash and charge them a hefty management fee—usually 2% of assets per year—for the privilege.

PE firms typically lock up investor funds for at least five years to allow time to spot good investments. After this period, they’re required to give remaining funds back or ask for more time (generally in exchange for lower fees or other concessions). Especially desperate firms succumb to the pressure and spawn “zombie” funds, giving up on fundraising altogether and subsisting on management fees while investors await the end of their lock-up periods. Nearly $120 billion (pdf) in assets is trapped in these doomed funds. No wonder investors are making PE firms sweat before they part with more cash.