Climate change is creating a new kind of grief, and we’re completely unprepared for it

The young man believed he only had five years to live. “Not because he was sick,” said Kate Schapira, “not because anything was wrong with him, but because he believed that life on Earth would be impossible for humans.”

The young man believed he only had five years to live. “Not because he was sick,” said Kate Schapira, “not because anything was wrong with him, but because he believed that life on Earth would be impossible for humans.”

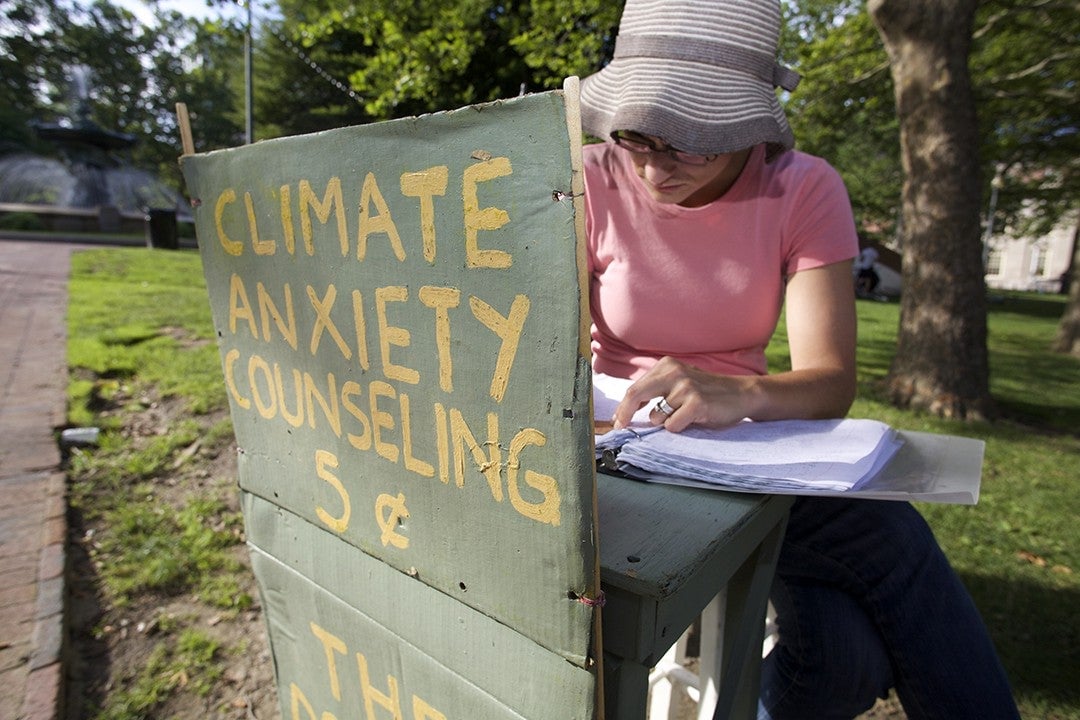

The sign on Schapira’s booth read: CLIMATE ANXIETY COUNSELING 5¢ THE DOCTOR IS IN. Time to earn her pennies.

On that muggy June day, she had set up shop in Kennedy Plaza in downtown Providence, Rhode Island. Schapira is not a trained therapist—a fact she makes clear to visitors—but she is happy to chat with anyone suffering from anxiety about climate change. “A lot of what I do is listen and ask questions,” she said.

Over the coming decades, rising temperatures will fuel natural disasters that are more deadly than any seen in human history, destabilizing nations and sending millions to their death. Experts say that we need to prepare for a hotter, less hospitable world by building sea walls, erecting desalination plants and engineering crops that can withstand punishing heat and drought, but few have considered the defenses we need to erect in our minds. Some, like Shapira, have called for more talking, more counseling to process our grief. But will that be enough? Climate change will do untold violence to life on this planet, and we have remarkably few tools to deal with its emotional cost.

It was a slow day when Schapira spoke to the young man. She recorded the number of dogs who scampered past—four—and the number of skateboards—more than 20. She also tallied the number of visitors—12—drawn to her booth, stationed just across the river from Brown University, where she teaches English literature. She looked up from her sign and updated her notes. Number of people who recognized the Peanuts reference—two.

The tall, sharply dressed man said humans were a cancer on the Earth. He said that he resented his parents for raising him to be “super hedonistic, just monstrously gaining things.” He said he had grown nihilistic, that he wanted to take up chain smoking and die a slow death. When Schapira asked if he was angry at his family, the young man replied, “I love my family. It’s so hard to know that you only have five years left to love people.”

The man was undoubtedly troubled, his vision of the future decidedly more apocalyptic than the one offered by science. But, his anxieties were real and, perhaps, understandable given the dire predictions of climatologists. While none believes human civilization will crumble in the next five years, the forecasts get hazier 30, 40 or 50 years down the road.

If we continue pumping out heat-trapping carbon pollution at the current rate, temperatures will rise by 4C by 2100, a level of warming climate scientist Kevin Anderson has called “incompatible with an organized global community.” As David Wallace-Wells explained in his bracing account of the terrors of climate change for New York magazine, “Indeed, absent a significant adjustment to how billions of humans conduct their lives, parts of the Earth will likely become close to uninhabitable, and other parts horrifically inhospitable, as soon as the end of this century.”

Climate change promises to take a massive toll, not just on nature or human society, but on our minds. Shapira’s conversation with that distraught young man offers as terrifying a glimpse of our future as any hurricane, heat wave or flood. In the years to come, the carbon crisis will work its way into our brains, sewing the seeds of fatalism, pessimism and despair.

Mental health professionals are just beginning to grapple with this fact. Renee Lertzman, a psychologist who studies the mental and emotional dimensions of climate change, believes few people have managed to process their grief about the slow decay of life on Earth. She said that many people are caught in “a state of arrested mourning,” what she calls “environmental melancholia.”

“The reason why, I think, we have a pervasive environmental melancholia is directly related to the fact that we’re not really talking about this,” Lertzman said. While psychologists have developed ways of grappling with the death of family member or the loss of a job, experts are still learning how to dislodge anxieties about climate change. Like Schapira, Lertzman recommends talking.

“We’re kind of getting validation or affirmation,” when we talk, she said, “Like, ‘Okay, what I’m feeling makes sense. It’s making sense to someone else. It’s not crazy.” Lertzman embraced the idea while a freshman at UC Santa Cruz, darting between classes on environmental science and psychology. “I was incredibly distressed about what I was learning about in the environmental studies course,” she said. “The big story was that humans had seriously gone awry.”

She described the disconnect between her time in the classroom, where she was learning about the multitude of poisons seeping from smokestacks and tailpipes, and her experience outside, where students luxuriated in the California sun, blissfully ignorant of the disasters to come. That year, Lertzman joined other budding environmentalists on a backpacking trip across the Sierra Nevada. Hikers spoke candidly about their fears, anxieties and frustrations. “It’s rare to have a small group of 10 or 12 people where you’re really spending a lot of time together, and you’re talking all the time about what you’re feeling and thinking,” she said, adding that the experience was affirming, cathartic even.

Lertzman explained that to grasp the full implications of climate change is daunting—to recognize our part in it all the more so. To fire up a car or step onto an airplane is to defile the very air we breathe. People cope by disavowing their role in climate change. “You’re not denying something, but you are choosing not to know,” Lertzman said. “There rarely is genuine apathy,” she added. “What shows up as apathy is a defense mechanism. It’s a way for people to cope with the very complicated feelings that come up around these issues.”

Like Lertzman, other mental health professionals have warned of the mental and emotional impact of climate change. Psychiatrist Lise Van Susteren coined the term “pre-traumatic stress disorder” to describe the pervasive dread felt by many scientists, advocates and journalists. In the years ahead, she said, the problem will only grow more widespread.

Van Susteren is the co-author a 2012 report on the psychological risks of the carbon crisis. Like other studies on climate change and mental health, the report warns of anxiety, depression, violence, suicide and drug abuse in the face of increasingly perilous storms, heat waves, floods and drought. As the authors noted, “The American mental health community, counselors, trauma specialists and first responders are not even close to being prepared to handle the scale and intensity of impacts that will arise from the harsher conditions and disasters that global warming will unleash.”

In response to growing climate anxiety, a handful of psychotherapists are pioneering a new field of treatment, termed “ecopsychology.” Doctors are urging patients to accept their own powerlessness and take breaks from computers and phones to meditate or work in the garden. Recent disasters underline the need for more work in this field.

Hurricane Maria sparked a mental health crisis in Puerto Rico, with many on the island suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. Following years of decline, the suicide rate spiked in the months after Maria struck. What’s notable is not just that people were shaken by the catastrophic storm, but that they had become increasingly fearful about the future, often to the point of paralysis.

“When it starts raining, they have episodes of anxiety because they think their house is going to flood again,” Dr Carlos del Toro Ortiz, a clinical psychologist based in San Juan, told the New York Times. “They have heart palpitations, sweating, catastrophic thoughts. They think ‘I’m going to drown,’ ‘I’m going to die,’ ‘I’m going to lose everything.’”

In northern Canada, where temperatures are climbing more rapidly than elsewhere, researchers have recorded grief and anxiety among the native Inuit. Those in Rigolet, a town on Canada’s eastern shore, rely on a network of frozen rivers and streams to reach hunting and fishing sites. Rising temperatures are melting these avenues, leaving residents stranded.

“If a way of life is taken away because of circumstances you have no control over, you lose control over your life,” an Inuit man said. Adding to the burgeoning lexicon of climate dystopia, researchers used the term “ecological grief” to describe what they saw.

It was with the goal of confronting ecological grief that, in 2014, Schapira came up with the idea for her booth. “I was just feeling very terrible and helpless, and also feeling like, in the terribleness and helplessness, I didn’t feel capable of articulating those feelings. I didn’t have a good way of talking about climate change with people that acknowledged its seriousness and its direness and the direness of its effects and how I was feeling about those things,” she said. “So, this is just a way that I made up to try to break down that isolation and maybe build a shared vocabulary around climate change and climate anxiety.”

She said that some visitors brush off the risks of climate change. “One person was like, ‘God made the world for us, and he’s not going to let anything bad happen to us.’ One person was like, ‘Oh, the government wants you to think this so they can control you more.’ I think one person was like, ‘Oh, it’s just part of the natural cycle. Everything evolves and everything dies,’” Schapira said. Sometimes, people commit to hopelessness, a view she describes as, “Look how right I was about how bad things are!”

More often, visitors discuss their more mundane anxieties of family, job and life—the quotidian worries that distract from their larger fears about the fate of the world. When they do talk about climate change, there is a disconnect between the size of the problem and their own role in addressing it. Fossil fuels could bring a hasty end to human civilization, and the answer, we’re told, is to change our light bulbs or take a bike to work.

Schapira has struggled to find a way to talk about climate change that acknowledges the enormity of the problem without leaving people feeling helpless. While she is committed to the fight, pointing visitors to opportunities for local action, she also struggles with feelings of powerlessness. She is profoundly worried about the future, so much so that she has decided not to have children, fearing what climate change will bring.

Visitors are sometimes flippant about their feelings of impotence. Schapira recalled a conversation with a group of teenagers who were fretting about Donald Trump. “When you’re eighteen, you can change the world. Every generation has a chance to change the world,” said one young man, feigning earnestness. Then, in a mocking tone, he added, “But ain’t nobody tryin’ to do all that work!”

Some, like the young man who believed that he only had five years to live, stare unblinkingly into the abyss. “That conversation actually ended with us sitting on the ground together, holding hands and crying, which is not something that I usually do,” Schapira said. “That was a hard day.”

It is challenging to recognize the size and scale of the problem and at the same time consider how little any one person can do to stop it. “Facing the hard truths of our climate crisis takes steady courage and a certain amount of grit,” wrote Jennifer Atkinson in High Country News. She added that “the young people I’ve met who are preparing for environmental careers are choosing not to look away… That doesn’t make them snowflakes. It makes them badasses.”

Climate change is a uniquely intractable problem, and it takes tremendous bravery to look it in the eyes. But, this is not the first time that humans have faced an overwhelming danger. From history come numerous examples of how we might think, feel and respond in the face of an existential threat.

Psychotherapist Rosemary Randall said Winston Churchill’s wartime speeches offer a model for how to handle our anxiety about climate change. Churchill, she wrote, “manages to tell a very stark and frightening truth. He is blunt about the scale of the problem, refuses to blame, makes emotional connections with his audience, uses stories to make his points, expresses his confidence in the abilities of the population, is realistic about the difficulty of what he is demanding of people. The alarming information is there but it is offered in a way that allows people to think and offers them some agency.”

That is remarkable when considered in the dim light of 1940. That year, France fell to the Nazis, and for the next several months, German aircrafts pummeled English cities and towns, killing tens of thousands of civilians and demoralizing millions more. While Britain tended its wounds, just across the English Channel, Europe’s fiercest military force prepared for a bloody invasion. This, Churchill said, was Britain’s darkest hour.

But Churchill did not shy from the darkness. He previewed the difficulty that lay ahead with honesty and courage. “We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering,” he said. If we fail, he warned, “then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.”

He did not dwell on the darkness, however. Instead, he issued a call to arms. “We shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches. We shall fight on the landing grounds. We shall fight in the fields and in the streets. We shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender,” he said. “You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory. “Victory. Victory at all costs. Victory in spite of all terror. Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival.”

Climate change is a problem with the scope and urgency of World War II, and while it will unfold more slowly and less predictably than the war, it demands a response on the same scale. Like the war, rising temperatures threaten violence, depravation and the deaths of millions. Writing in The New Republic, author and activist Bill McKibben, argued, “By most of the ways we measure wars, climate change is the real deal: Carbon and methane are seizing physical territory, sowing havoc and panic, racking up casualties, and even destabilizing governments.” And, like the war, climate change demands the massive and immediate mobilization of American industry.

And so, faced with overwhelming odds, we might do as Churchill would. Acknowledge the difficult road ahead. Feel our dread and despair. And then commit to do better. Understand that anxiety is not action. Worry is not resolve. In times of crisis, people want to be soldiers, not victims. They want to feel community, solidarity and empowerment. This, perhaps, is what Schapira sought in setting up her humble wooden booth. Filled with dread, she took up arms against that which she feared most. “I’m asking people about their anxieties that have to do with climate change,” she tells visitors.

“Is there anything that you would like to talk about today?”

This post originally appeared on Nexus Media.