Playing this board game will challenge your ideas about refugees

When immigrants come to Canada, they have to quickly adapt and they have much to learn. Many of them need to learn a new language and a new culture.

When immigrants come to Canada, they have to quickly adapt and they have much to learn. Many of them need to learn a new language and a new culture.

The Canadian government defines integration as a two-way street. Newcomers strengthen the Canadian economy by bringing diverse perspectives which can lead to better workplace outcomes, innovation and strong community connections.

As an educator working with newcomers for the past decade, I have seen a need not just for newcomer education (such as language classes, settlement services and community orientation) but also for formal and informal education for the Canadians who make up the welcoming group.

The need for education tools

Front-line workers have some effective tools that serve to educate Canadians about our diversity: things like the “privilege walk,” which aims to demonstrate our varying degrees of privilege based on our identities. We also have poverty simulations and forced migration simulations.

Yet none of these address experiences of integration. We have some methods to help volunteers understand refugee newcomers, but they tend to focus on their journey to the refugee camp, or on sponsorship to Canada. So far, the education has ended there.

I wanted to build a tool that would help existing residents of Canada and volunteers at newcomer centers understand what it feels like to enter a new country and to try to build a life.

I envisioned a tool that could explore integration in a way that would be engaging, practical and portable. I wanted the tool to help foster deep discussion and to bring relevant research on refugees and integration into an accessible sphere. So as part of a research project in my doctoral program at the University of Manitoba I developed and launched a board game. My goal is to be able to work with future educators who will be able to examine their own identities, privilege or lack thereof, and motivations for becoming teachers.

I hope this game, called Refugee Journeys: Identity, Intersectionality and Integration, will help to foster a deep appreciation for diversity and a nuanced understanding of how identity shapes the practice of both teachers and front-line volunteers.

Combating prejudice

Canadian and western attitudes and policies to newcomers can be prejudiced.

In a study of Canadian media coverage of Syrian refugees, we learned that Canadians tend to view refugees as needy and themselves as generous. This simplistic view fails to recognize the diversity of human experiences and the resilience and strength that newcomers can bring.

For example, we hear things like how all refugees should be eternally grateful. Ideas like this paint all refugees as monolithic. Rather, we should view them as complex human beings with a full range of emotion.

We’ve all heard stories of newcomers who get stuck in “entry-level” employment despite coming to the country with high levels of background expertise. In a recent panel interview, Calgary mayor Naheed Nenshi called this the great “bait-and-switch” of the Canadian immigration system.

I saw this paternalistic attitude in my classrooms and community work. Some examples are the extra loud and slow speech of language helpers, the unnecessary explanations of everyday activities, the comments about how lucky they are just to be in Canada and the insistence on learning about “Canadian experiences” like hockey, Tim Horton’s and tobogganing.

I began to wish I could become an educator not just of newcomers, but of mainstream Canadians as well. Power, place and belonging are not easy concepts to challenge.

Developing the game

The game, Refugee Journeys, which was created with the help of designer Rob Gosselin, is based on the theory of intersectionality, and looks at the intersections of race and gender and how one can be discriminated against in multiple and intersecting areas.

The ideas of intersectionality have now expanded into ideas about how the marginalization of particular groups is multifaceted and based on connections between many identity markers, layers of systemic discrimination and sociopolitical forces.

As I developed the game, I drew from the work of many scholars, including sociologists: Floya Anthias, who writes about the complexity of identity and belonging; Victoria Esses, who analyzes both the dehumanization and resistance of refugees in Canada; and Michael Apple, who calls on educators and policy-makers to consider the unforeseen consequences of their actions on those with the least amount of power.

Playing the game

To play the game, each player is given an identity card, which details different aspects of their identity. Once you have your “game identity,” you are ready to go.

As you progress through the game, at different places your identity becomes a factor in your integration pathway. If you are Muslim in the game, you move back two spaces.

These experiences highlight systemic discrimination and they are incredibly frustrating, especially if you are using a card that highlights a very different identity than your usual one.

As you play the game, you pick up different experience cards, drawn from a variety of sources: Academic literature, news articles and personal experience. The game progresses like this: You move forward and backward, or miss a turn, depending on the cards that you draw. This experience highlights the individual nature of integration, and in so doing asks players to understand what it feels like to go through such experiences.

After each experience card is played, players have a discussion guided by questions on the board. The questions allow for deep engagement, including a question about personal experiences.

Since players can choose which questions they wish to discuss, sharing personal experiences is not mandatory. It is an option to share if you wish.

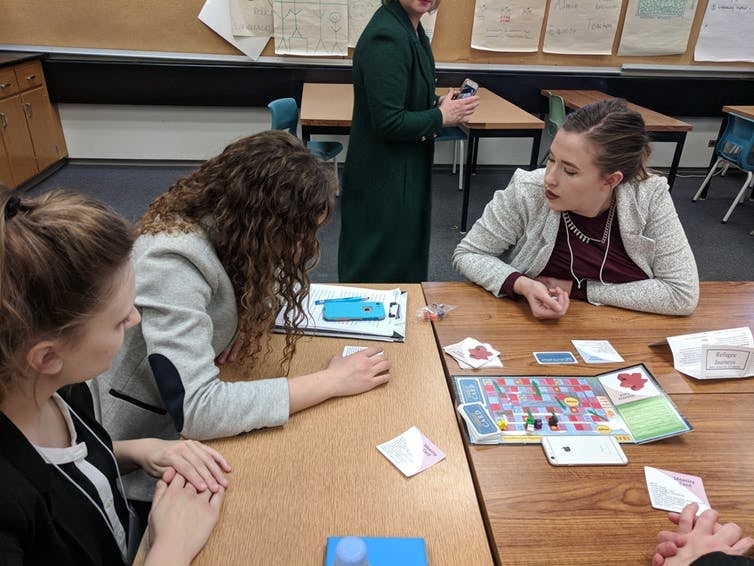

The game has been used with high school students, university students studying to be teachers, and with graduate level students at both OISE (Ontario Institute for the Study of Education) and the University of Manitoba.

The next steps include working with refugee-sponsoring groups, settlement service providers and teachers who work with newcomers as part of their diversity training. I plan to develop a website for the game, and to build an option for collaboration so people can use this game as a framework or template, and then add their own experiences or relevant research to be incorporated into future versions.

After one game, a player summed it up nicely: “Refugee experiences are very diverse and we can’t paint them with one brush. The game encompasses the values of empathy and social consciousness.”

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.