Humans should stop meddling with pandas and let them die

About 183,000 years ago, early humans shared the Earth with a lot of giant pandas. And not just the black-and-white, roly-poly creatures we know today, but another, previously unknown lineage of giant panda bears as well.

About 183,000 years ago, early humans shared the Earth with a lot of giant pandas. And not just the black-and-white, roly-poly creatures we know today, but another, previously unknown lineage of giant panda bears as well.

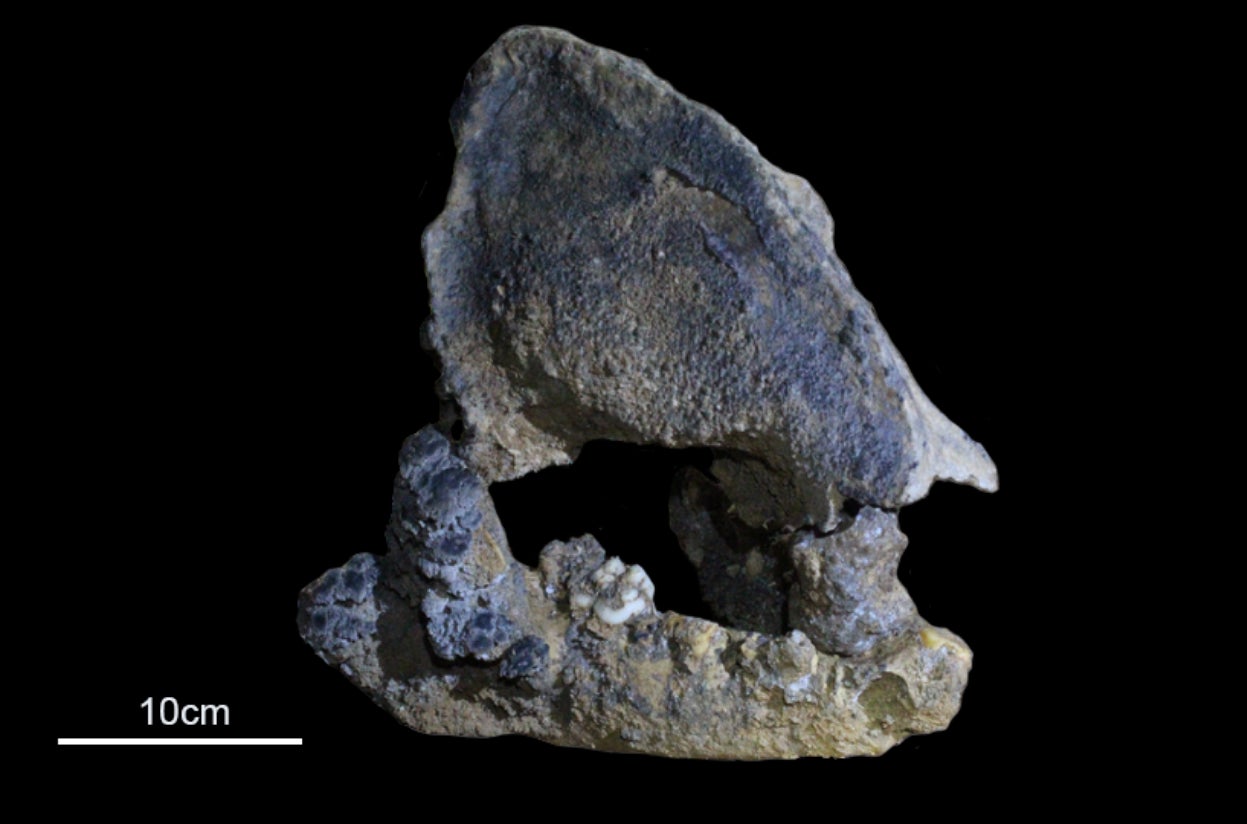

In a paper published Monday (June 18) in Current Biology, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences upend the prevailing theory that pandas evolved from other bears some 20 million years ago. After analyzing 150,000 fragments of mitochondrial DNA from a 22,000 year-old panda skull found in a cave in southern China, the team realized that the creature didn’t quite match up with modern pandas. They compared DNA from this skull—which was the oldest remnant of an ancient panda bear found to date—to the DNA of 138 modern pandas and 32 samples of other ancient bears. They concluded that some 183,000 years ago, a common Ursus ancestor split off into two lineages: the modern day panda bear, and this other ancient animal.

The skull gives researchers a rare glimpse into the history of these bamboo-loving floofers, and of bears in general. In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature declassified (paywall) pandas from “endangered” to “vulnerable”—the same category as polar bears and white sharks—but there are still only about 2,500 loafing around the planet. With so few pandas samples available, it’s been hard to trace their history.

But…who cares where pandas have been? Perhaps more importantly, why are we trying so hard to keep them alive? This is a subject that has been of sustained and passionate debate among the Quartz science team since its formation. We decided to use this study as a launching pad to finally crystallize these arguments, which, though superficially silly, actually have import for larger questions about conservation and environmentalism.

Pandas don’t deserve all our love

Katherine Ellen Foley:

Pandas are, at best, cute doofuses who lumber and roll around snacking on some 40 pounds of bamboo daily. Their bodies are ill-equipped to handle the highly fibrous nature of bamboo, but they insist they love the stuff. You could argue that humans are not exactly biologically disposed to eat everything that we do, either—does anyone really need fried Oreos? But at least we’re much better at sex.

Evolution itself has made it difficult for pandas to keep populating the planet. Pandas in the wild have a mating ritual that goes on for weeks, despite the fact that females are only fertile a few days per year. As Live Science reports, this coital precursor involves a bunch of male pandas fighting for a single female hanging out in a tree until she’s ready to come down. She then has to take a bit of a leadership role to position herself to be inseminated, because male pandas have evolved to have some of the smallest penises relative to their bodies of other animals on the planet.

Obviously, difficulty breeding is not necessarily pandas’ fault. Humans have made it harder for pandas to get it on by fragmenting their natural habitats with road construction, deforestation, and the effects of climate change.

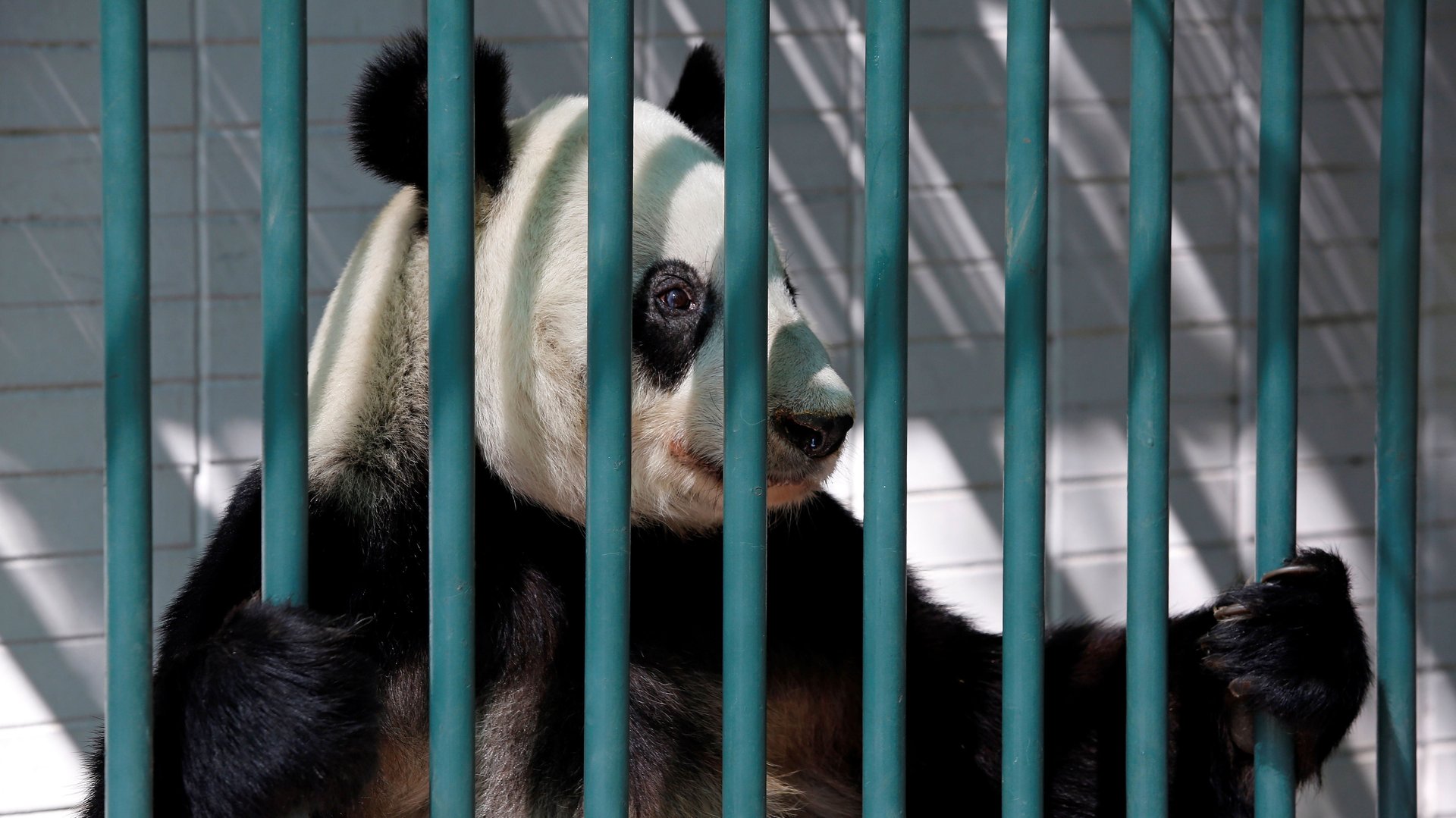

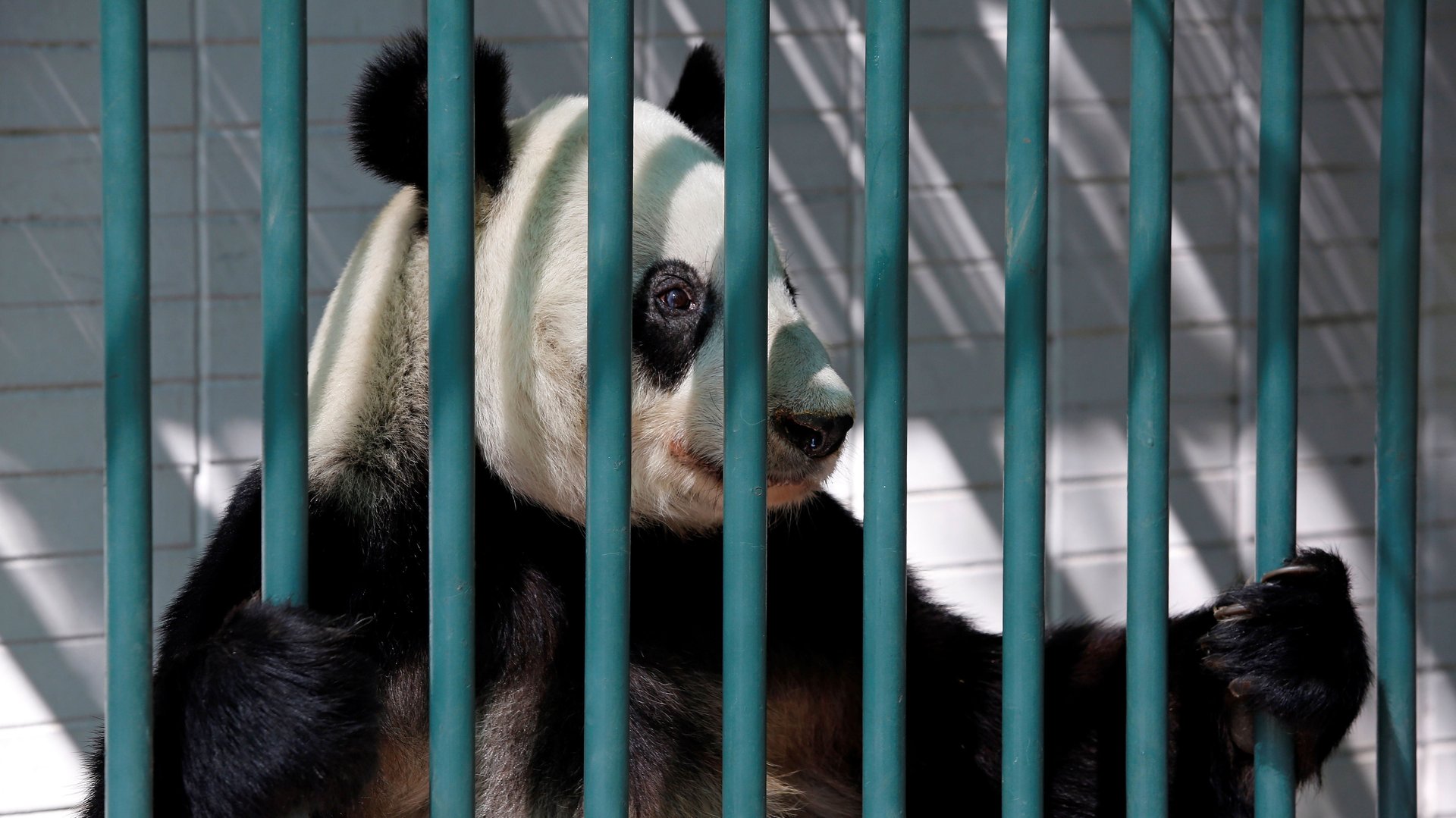

But even in captivity, where some of these barriers should be eliminated, pandas have a hard time mating. Although scientists can’t say for sure, it seems female pandas prefer being fought over by their male counterparts and copulating with the winner. In captivity, panda ladies have been known to reject the male, perhaps because he doesn’t have a chance to prove that he is a worthy suitor.

And if a panda does manage to get pregnant, she normally has one cub at a time, which emerges from the womb only weighing less than a pound—one of the smallest offspring compared to parent size. It’s not uncommon to hear about a panda cub dying in captivity because they’re so vulnerable.

At this point, pandas are mostly just a symbol of diplomacy and goodwill between China and the foreign countries that keep pandas in their zoos. That political gesture doesn’t come cheap: Pandas cost zoos roughly $1 million per year to rent from China, plus a one-time tax on each baby born, plus specialized medical care for the entirety of their 20 to 30 years on the planet. This usually adds up to millions of dollars per year, depending on the zoo’s location. Although zoos tend to profit from having pandas in terms of attendance and merchandise sales, it doesn’t always seem like pandas are thriving there either. Similar to white sharks, pandas prefer an open environment where they can roam freely. Even the biggest enclosures cause them to get a little wacky, sometimes biting zookeepers, other pandas, or even mating with the wrong body part.

We owe it to pandas—and other creatures—to restore their habitats as best we can. But then we should wish them well and leave them alone. If they die out, at least other creatures who are better suited for procreating and sustaining themselves will survive.

Pandas are the best

Olivia Goldhill:

Even those who believe panda bears should die out can’t help but acknowledge how great they are. “Pandas are, at best, cute doofuses who lumber and roll around snacking on some 40 pounds of bamboo daily,” writes my colleague, Katherine. Precisely! What, pray tell, is better than a cute doofus who lumbers around snacking on copious amounts of bamboo?

I could write all kinds of eloquent arguments, but pandas make the most convincing case for their existence simply by being adorable.

Yes, they might get more conservation money than some other, less cute animals, and perhaps that isn’t entirely fair. And sure, they don’t do the best job of staying alive by themselves, what with their insistence on eating non-nutritious bamboo and difficulties mating.

But these animals are worth preserving, even with the high costs of their medical care. They’re more than just a pretty face, playing an essential ecological role by distributing bamboo seeds throughout the forest. Plus, as Popular Science points out, they act a bit like the British royal family of the animal kingdom, attracting tourism money to zoos and interest in animal welfare. (The British royal family do this for Britain rather than zoos and animal welfare, but you get the point.)

Most importantly, these tubby, furry creatures exude playfulness and bring joy to all but the coldest of hearts. Some things, like a Leonardo da Vinci painting or a species of black-and-white, cuddly bear, are worth preserving not for any utilitarian reason, but because they’re intrinsically wonderful. They’re valuable in their own right, rather than for some practical purpose. Anyone with a soul would mourn the day these beautiful creatures die out, and rightly so. Now, I’ll let pandas have the final word:

Pandas are really, truly the worst

Elijah Wolfson:

Have you ever heard of the yellow-faced bee? How about the mangrove-dwelling crab? Or the snake-river salmon?

No? None of them?

It might have something to do with the fact that none are even remotely as cuddly as the panda bear. And yet, these are three examples of animals that are not only endangered (that’s a more pressing classification than the panda’s current status), but, unlike the panda, are keystone animals for their ecosystems. That means we don’t lose just the bees and crabs and salmon—we lose the dozens of other animal and plant species that rely on them to survive.

And let’s be clear: Pandas are dumb. Panda bears are omnivores who are basically carnivores, biologically speaking —their “digestive system is more similar to that of a carnivore than an herbivore, and so much of what is eaten is passed as waste,” according to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. And yet, for some reason, they have decided not to eat meat and consume only bamboo. To make matters worse, they can’t actually survive by eating normal amounts of bamboo. As the Smithsonian notes, because their stomachs aren’t designed to digest plants, pandas get almost no nutrients out of bamboo before they pass through their systems as waste. So pandas have to eat tons and tons of the plant just to stay alive—so much bamboo that we humans have to go out and plant extra bamboo for them to eat cause they’ve already housed everything that grows naturally. In the meanwhile, you know what else lives in their habitat? Toads, newts, and frogs; many, many birds far smaller than a bear; field mice, shrews, squirrels, voles, hares, moles, weasels, monkeys, and civets; and snakes, turtles, and fish. This is not the Hunger Games.

And yet pandas choose not to eat any of those things, and as a result can’t get the nutrients they need unless we feed them. I can think of maybe one or two animals like that (yes, cats and dogs), but both are that way specifically because we domesticated them.

I don’t want to come off as a curmudgeonly pragmatist; I am in full agreement with my colleague Olivia’s assertion that “some things are worth preserving not for any utilitarian reason, but because they’re intrinsically wonderful.” But what if you could have both? I submit to you that all of the world’s goodwill towards panda bears could very easily be shifted onto sea otters, which are equally adorable, but also serve an essential ecological purpose in their Pacific Ocean habitat.

I get that animal conservation is not a zero-sum game in theory. But sadly, it is a zero-sum game in practice, because we only have so many resources to fund animal conservation. Given that reality, I think pandas should get to the back of the line, far behind the yellow-faced bees, the mangrove-dwelling crabs, the snake-river salmon, the sea otter, the gopher tortoise, the tiger shark, the prairie dog, the ivory tree coral, and so many more.

I think my colleague Olivia is right to draw the connection between pandas and the UK royal family. Both serve as propaganda designed to uphold an ideal of their respective governments, and both end up costing the taxpayers in those countries a fortune. In the UK, the annual cost of the monarchy (pdf) is £345 million ($457 million).

That said, compared to royals, pandas are a relative bargain. China committed $1.5 billion this past March to build a massive panda bear sanctuary—but that’s more or less a one-time cost. Three years of Harry and Meghan, or decades of pandas? Maybe they don’t need to die, after all.