The one time Americans really rallied to welcome asylum seekers

America’s attitude toward refugees is hardening. After banning refugees from war-torn countries like Syria and Yemen, the US this week launched tear gas at Central American asylum seekers on the southern border. Meanwhile, only 51% of Americans think they have a responsibility to admit refugees. Less than half think the US should do more to help them.

America’s attitude toward refugees is hardening. After banning refugees from war-torn countries like Syria and Yemen, the US this week launched tear gas at Central American asylum seekers on the southern border. Meanwhile, only 51% of Americans think they have a responsibility to admit refugees. Less than half think the US should do more to help them.

When European Jews were fleeing persecution in WWII, the US was similarly reluctant to help; the government turned away thousands, with little objection from the American public. But there is one moment in US history when the government and public rallied together to welcome large numbers of refugees: The Armenian genocide, which lasted from 1914 to 1923. In those years, US citizens launched an unprecedented grassroots aid fundraising campaign, while the US government opened its borders to nearly 80,000 Armenians.

Other large numbers of refugees have been welcomed at other times—100,000 Vietnamese refugees eventually entered the US after the Vietnam War—but the Armenian crisis stands out for the extraordinary outpouring of sympathy and aid that it elicited from the American public .

How America discovered a genocide

On Jan. 11, 1915, the New York Times published an article that warned of “a massacre of the Christian population” in the Ottoman Empire and noted that “in Constantinople no endeavor is any longer made by the Ministers to hide their feelings toward their Christian subjects.” Henry Morgenthau, US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, described it as a “race murder.”

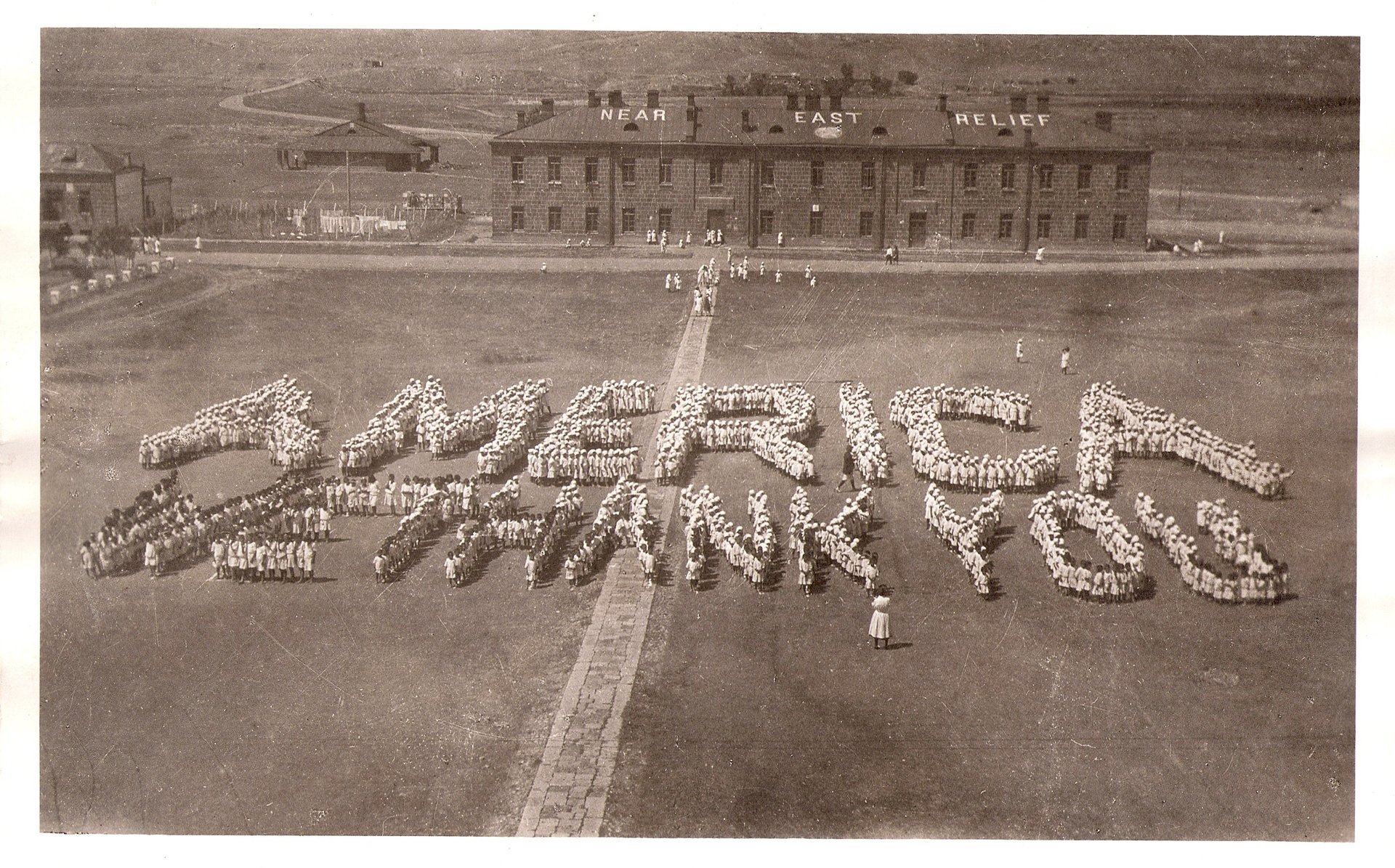

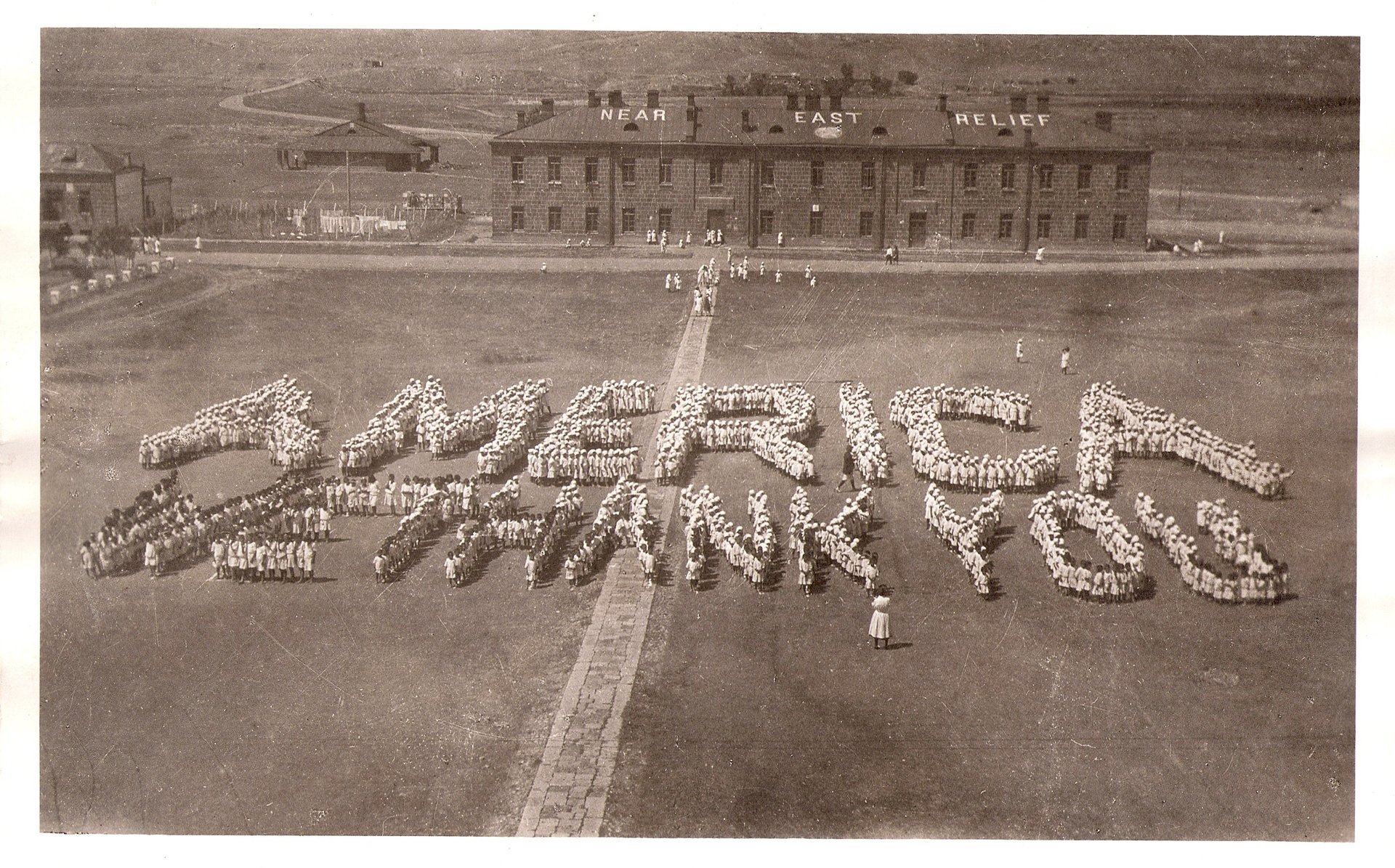

The term “genocide” didn’t exist yet (it would later be coined to describe the Holocaust), and to this day the US government does not recognize the mass slaughter of Ottoman Armenians as a genocide. Nevertheless, Americans mobilized to offer refuge to the victims. Historian Vartan Gregorian tells Quartz that private citizens were able to raise well $116 million (about $2 billion today) for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief (ACASR), which collected the money, managed volunteers to help victims, and distributed aid to Armenians through missionaries and the American embassy in Constantinople (now Istanbul).

Mostly funded through grassroots donations, the initial goal for the fundraiser, $30 million (about half a billion dollars today) was reached in 1931, collecting up to $90 per Armenian citizen (over $1,500 per capita today). The ACASR (today’s Near East Foundation) also enjoyed the support of then-president Woodrow Wilson. Some Americans gave more than money; over 1,000 people traveled overseas to provide humanitarian relief to the Armenians by setting up orphanages, camps and hospitals.

By comparison, USAID gave $61 million to Rwanda after the genocide in 1994 (amounting to $10 for every Rwandan) and the government was slow to even acknowledge that a genocide was happening. More recently, USAID has given $7.7 billion for the Syrian people since 2011 ($420 per capita), while Syrians themselves have been banned from traveling to the US.

A blueprint for American generosity

The US response to the genocide created a template for US philanthropy to come. Gregorian notes that the Armenian crisis marked the first time individual Americans stepped forward to financially support to victims of conflict.

Today, many Americans still consider charity a personal responsibility. Americans lead the world for individual charitable donations per capita outdoing their government in generosity. ”Every year,” says Gregorian, “Americans give $400 million in private donations to charity, and there are 1.6 million registered civil society organizations…[American humanitarian efforts] don’t need government support,” says Gregorian.

According to Gregorian, as well as Henry Theriault, the editor of the Genocide Studies and Prevention journal, here’s what made such grassroots fundraising possible:

- The US press covered the genocide extensively, which was not the case during the prosecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. The massacre of the Armenians became such a part of the American conscience, says Gregorian, that their plight entered the vernacular, with sentences like “finish your meal, think about the starving Armenians.”Today, 44% of Americans dismiss the news media as inaccurate, and nearly 60% of Americans (pdf, p. 16) believe there are too many humanitarian crises around the world to keep up with. Little wonder that half of all Americans polled don’t think the US should do any more to help refugees than it’s already doing.

- It was the first time that the American public faced a crime of that size and horror. The fact that the genocide orphaned thousands of children added urgency.

- US condemnation of the massacre was bipartisan, and inter-religious: Though the victims were Christian, Gregorian says that in addition to Christian groups, prominent Muslim leaders encouraged their fellow Muslims to extend help to the Armenians, both in the Middle Eastern countries that took them in (including Syria, Iran, Lebanon) and in the US.

- The US government got out of the way. Though the US didn’t intervene military to stop the genocide or donated government funds for its relief, it openly supported the relief efforts. For instance, it didn’t turn away refugees, which did happen to Jewish refugees during World War II.

- The timing. The 1920s were days of growing civil and human rights movements, from female suffrage to the Harlem Renaissance, and Americans were exploring their social conscience.

- The refugees were Christian. The massacre of the Armenians was perpetrated on a Christian minority within a Muslim majority country. The idea of a Christian minority being attacked by Muslims was a core element of the campaigning, particularly by missionaries in the Ottoman empire. (Today, Trump has emphasized a similar prioritization of Christian refugees in Syria.