New landmark study links herpes viruses to Alzheimer’s diseases

In a landmark study published June 21 in the journal Neuron, researchers connected two of the most ubiquitous viral infections to Alzheimer’s disease.

In a landmark study published June 21 in the journal Neuron, researchers connected two of the most ubiquitous viral infections to Alzheimer’s disease.

Scientists from the Icahn School of Medicine in New York City and Arizona State University collected over 2,000 tissue samples from 944 brains held at several brain banks funded by the US National Institute of Aging, which also provided money for the study. Some of the brain samples had the tell-tale amyloid plaques and tau buildups of Alzheimer’s disease, some had signs of other cognitive impairments, and some were healthy.

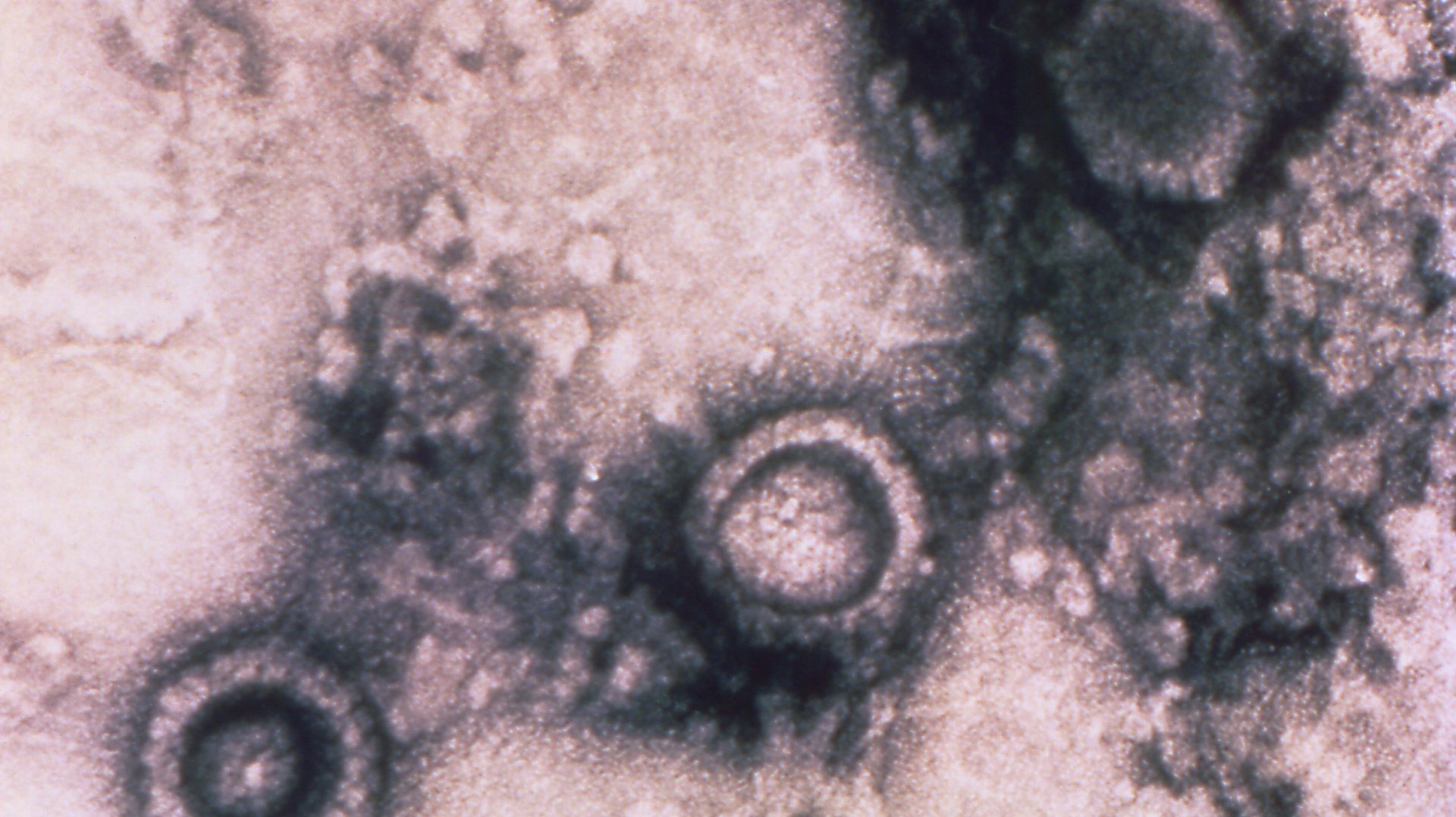

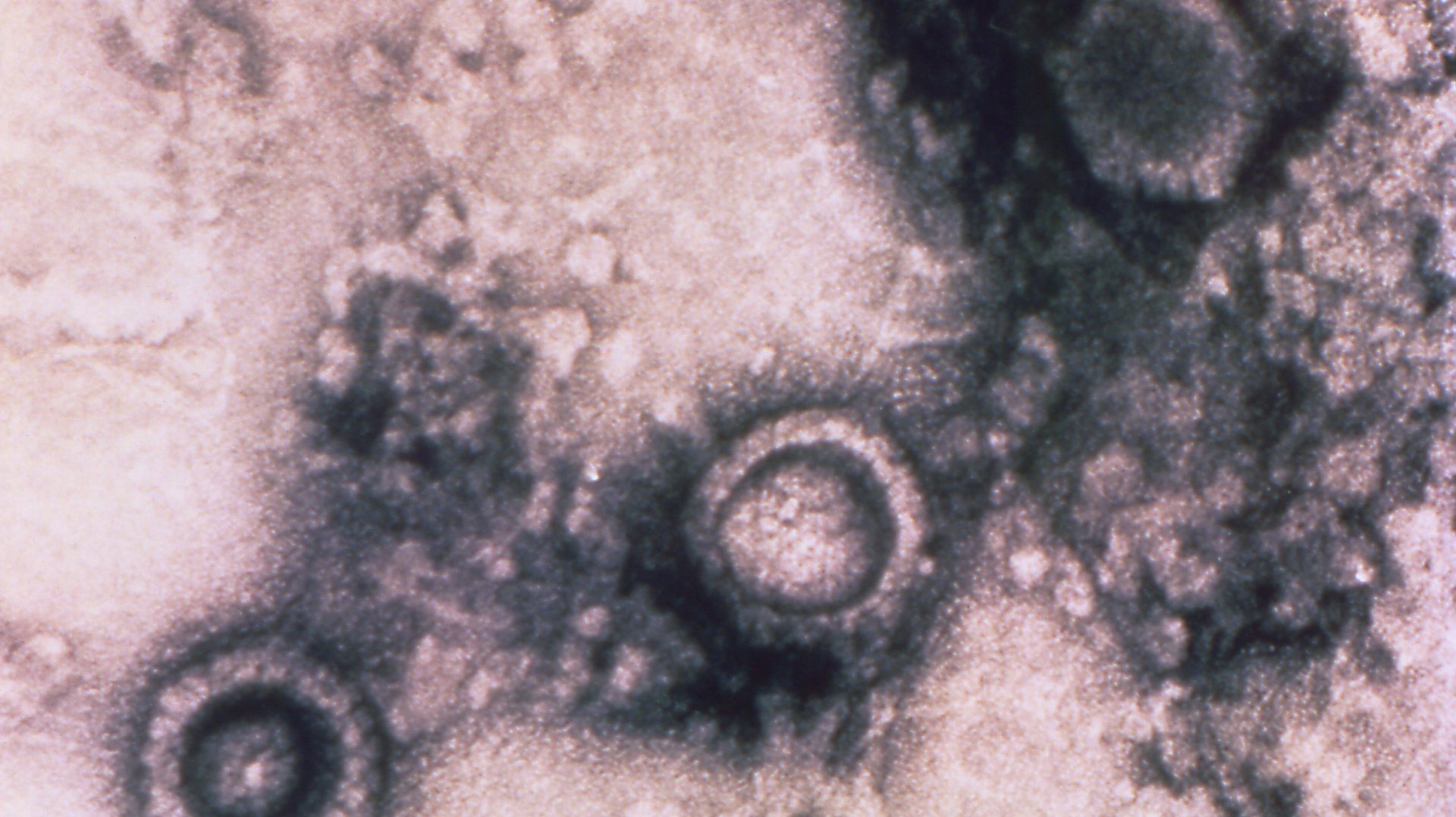

The team found over 500 types of viruses present in these brains. Two, however, stood out as existing in particularly high concentrations in brains with Alzheimer’s: a human herpes virus (HHV) 6 called HHV 6A and 7.

Of the nine herpes viruses that infect humans, these aren’t the ones you probably think of when you think “herpes.” (Those are likely herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, which can cause cold sores and genital herpes.) HHV 6 and HHV 7 can cause a mild rash in infants under the age of 6 months old, and, rarely, febrile seizures and vomiting, but for the most part, they don’t trouble us.

The peculiar thing about herpes viruses, though, is their ability to go dormant in the body, only to reawaken later to start replicating again. For example, the varicella zoster virus, the form of herpes that causes chicken pox, can stay dormant for years, and then reactivate later in life, causing shingles. The name herpes, in fact, is derived from a Greek word meaning “to creep” because of their ability to crawl up our nerves and plant themselves comfortably on our spines, or in the case of HHV 6 and HHV 7, our brains. Scientists have estimated that 90% of the US population over the age of 5 have had HHV 6 or 7, but may not have any symptoms. It’s difficult to estimate how many of these cases are specifically HHV 6A because it is only detectable via organ biopsies, rather than a blood test.

Yet, even while dormant, the viruses seem to be emitting low levels of proteins or genetic material that interact with genes known to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease. When they start actively reproducing, they appear to speed up the Alzheimer’s-related protein buildups that ultimately lead to system failure for the brain.

“Our hypothesis is that they put gas on the flame,” Joel Dudley, a geneticist at the Icahn School of Medicine and author of the paper, told NPR.

That’s just a working hypothesis, though. It doesn’t look like viruses themselves cause Alzheimer’s, and it’s also possible that it may be brain’s immune response to the virus that leads to protein buildups, rather than anything about the viruses themselves. Further, it could be that a person with a genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s makes them more susceptible to having active versions of these viruses.

The good news is, this research suggests two avenues of research for Alzheimer’s treatment. New therapies could either target the brain’s immune system to keep it less active, or they could treat patients with antiviral medical to keep the herpes virus at bay. At this point, any new ideas for treating Alzheimer’s are welcome; the disease has stumped physicians and pharmaceutical companies for decades.

Correction (June 23): An earlier version of this article said that HHV 6 was one of the viruses implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, and did not distinguish that it was specifically HHV 6A, which is a subtype of the virus. This piece has also been updated to show that the prevalence of HHV 6A is unclear, due to testing limitations.