Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis has brought the country to the brink of civil war

Cameroon’s governance and security problems have historically attracted little outside attention. But this seems likely to change, for two reasons. The first is the growing political crisis in the Central African nation’s English-speaking region. The second is a presidential election scheduled for October 2018.

Cameroon’s governance and security problems have historically attracted little outside attention. But this seems likely to change, for two reasons. The first is the growing political crisis in the Central African nation’s English-speaking region. The second is a presidential election scheduled for October 2018.

Roughly 20% of the country’s population of 24.6 million people are Anglophone. The majority are Francophone. The unfair domination of French-speaking politicians in government has long been the source of conflict.

Activists in the country’s Anglophone western regions are protesting their forced assimilation into the dominant Francophone society. They argue that this process violates their minority rights, which are protected under agreements that date back to the 1960s. Anglophone political representation and involvement at many levels of society has dwindled since the Federal Republic of Cameroon became the United Republic of Cameroon in 1972. There are growing calls for the Anglophone region to secede from Cameroon.

This festering conflict represents a major test as Cameroon prepares for the October elections.

Three things are urgently needed now in Cameroon. The first is to understand the origins of the crisis. The second is to support an inclusive national dialogue. And the third is to ensure that the 2018 elections are free and fair for all.

Growing crisis

Before 1961, the Southern Cameroons were a British administered territory from Nigeria. They elected to join the Republic of Cameroon by UN plebiscite in 1961 around the time of decolonization.

A power-sharing agreement was reached: the executive branch of government was meant to be shared by Francophones and Anglophones. But that agreement has not been upheld and, over the years, Anglophone political representation has been steadily eroded.

The crisis came to a head in late 2016 when lawyers, joined by teachers and others with similar grievances, led protests in major western cities demanding that the integrity of their professional institutions be protected and their minority rights respected.

President Paul Biya responded by deploying troops to the region and blocking internet access. When peaceful demonstrations were met with violent repression it exacerbated tensions and escalated the conflict to a national political crisis.

On June 12, Amnesty International issued a report documenting human rights violations in Cameroon. The International Crisis Group says that at least 120 civilians and 43 members of security forces have been killed in the most recent waves of violence.

More than 20,000 people have fled to neighbouring Nigeria, and an estimated 160,000 are displaced within Cameroon.

Some human rights activists worry that Cameroon could be the site of Africa’s next civil war.

Agbor Nkongho, an Anglophone human rights lawyer and director of the Center for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa, told the Washington Post:

We are gradually, gradually getting there (civil war). I’m not seeing the willingness of the government to try to find and address the issue in a way that we will not get there.

Another issue is that there are diverse views even within the Anglophone and Francophone communities about what would be best for Cameroon going forward.

Obstacles to national unity

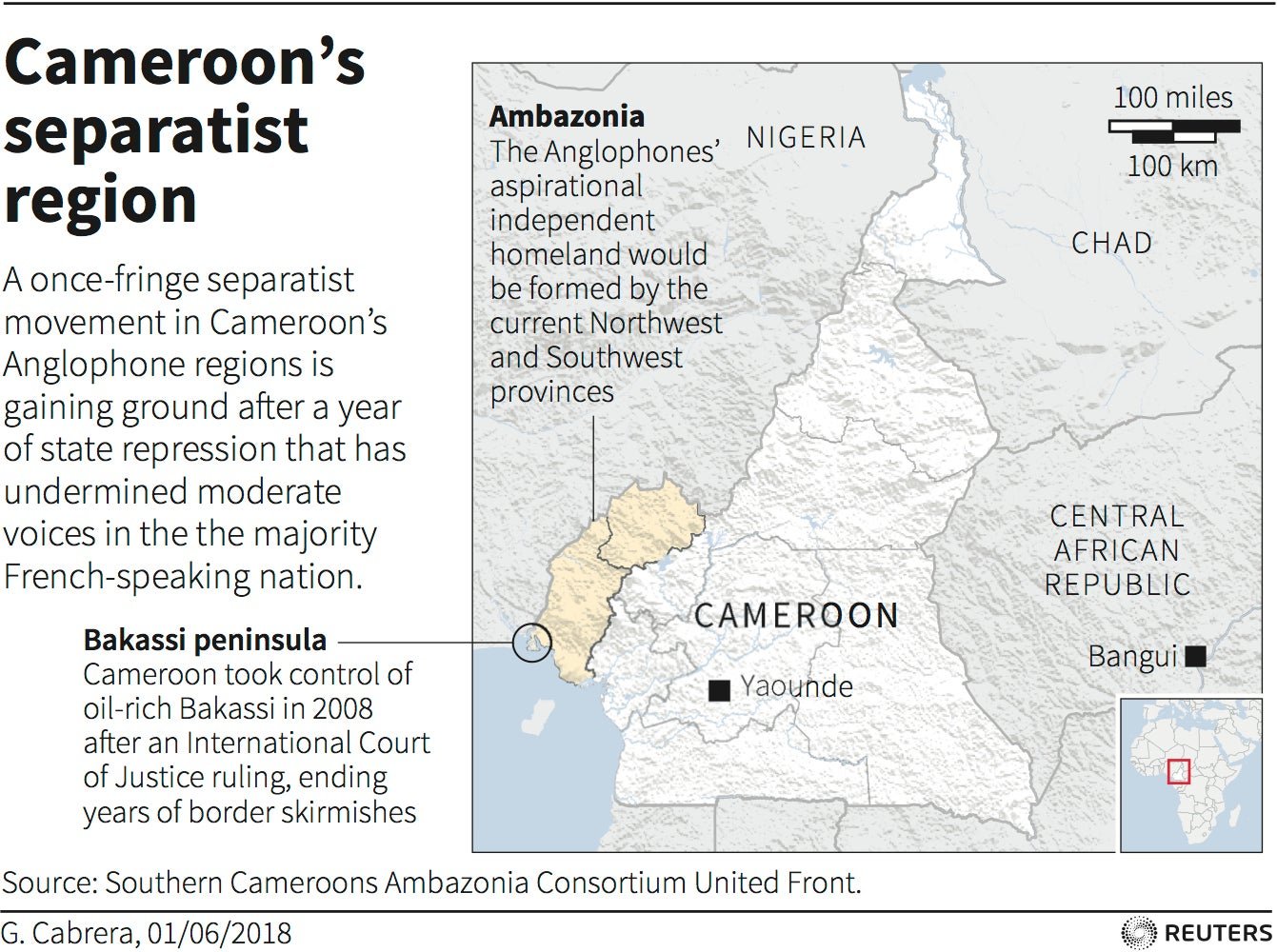

In October 2017 the separatist leader Julius Ayuk Tabe declared the independence of the Republic of Ambazonia. His interim government laid claim to a territory whose borders are the same as the UN Trust Territory of Southern Cameroons under British rule (1922-1961).

The interim government’s spokesman, Nso Foncha Nkem, invited Francophones to leave the region and called on Anglophones in Biya’s “rubber-stamp” government to return to Ambazonia and support the movement. He also pleaded for unity, asking that Anglophones speak in one voice.

However, that call has not overcome the challenges posed by diverse viewpoints within the Anglophone population itself. Some favor secession. Others want to return to the 1961 federation and the power-sharing agreement. There are those who prefer decentralization that would devolve power to regional leaders, and some who simply want an administrative solution that would leave the Republic of Cameroon as it stands.

And among the Francophone population, there is some support for the radical separatists, while some see the Anglophone situation as a general crisis of governance and others deny any problem exists.

Mongo Beti, a Francophone novelist and activist who spent 30 years in exile, observed after returning home in the 1990s that a general absence of identification with a viable, unified nation due to various divisions had frayed Cameroon’s social fabric and was a significant impediment to progress.

It is unclear whether Biya, who is 85 and in power since 1982, will run for re-election. His 38 years in office as a corrupt, absent leader have left the nation in tatters. The vast majority of Cameroonians, whether Anglophone or Francophone, are hungry for change.

The way forward?

There is an urgent need for an inclusive national dialogue to harness this desire for change.

The government must recognize that it faces a substantive national crisis and take extraordinary steps. A general conversation about governance in all its regions is also necessary. Given the depth and severity of people’s grievances, a holistic approach is needed that would address issues of governance, security, and civic engagement to mend the bonds that have been broken.

This is necessary if the current crisis it to become an opportunity to develop a new road map for the future that could empower citizens.

Phyllis Taoua is the author of African Freedom: How Africa Responded to Independence (Cambridge University Press, 2018) and was a Tucson Public Voices Fellow with the Op-Ed Project.

Phyllis Taoua, Professor of Francophone Studies (Africa, Caribbean), Faculty Affiliate with Africana Studies, World Literature Program and Human Rights Practice, University of Arizona

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.