The racist tweets following Osaka’s earthquake echo a dark moment in Japanese history

Early in the morning on June 18, shortly after a 6.1-magnitude earthquake struck Osaka, reports of a loose zebra started to show up on Japanese Twitter feeds.

Early in the morning on June 18, shortly after a 6.1-magnitude earthquake struck Osaka, reports of a loose zebra started to show up on Japanese Twitter feeds.

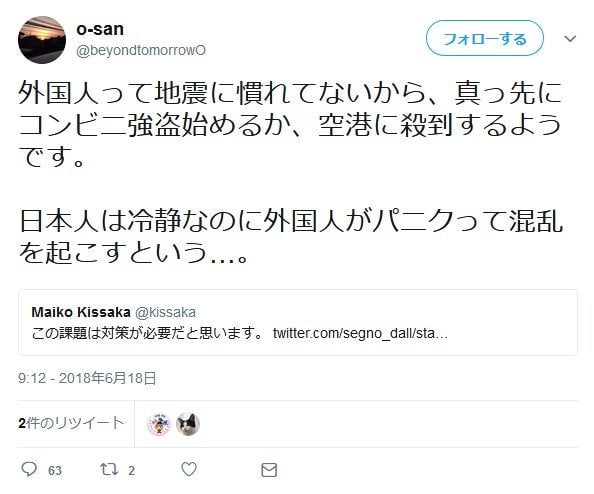

They were fake. And the zebra wasn’t the only inaccurate piece of “news” that started to spread online after the quake. Among the false reports were cautionary messages about foreigners supposedly looting buildings and poisoning water sources. In one such message, Twitter user O-san warned that foreigners (gaijin) are not accustomed to earthquakes, and so would start robbing convenience stores and rushing the airport.

Later that day, O-san deleted his original tweet, and apologized for spreading the rumor. ”I apologize for the trouble I caused with my childish remarks,” he tweeted, adding that he prays for the lives lost and a speedy reconstruction effort.

In Japan, fake news often follow earthquakes, which makes sense, given that the seismically active country sees some 150 quakes of 6.0 magnitude or greater every year on average. From the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake that triggered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear collapse to the more recent Kumamoto earthquake (link in Japanese) in 2016, disasters have almost always spurred alarmist rumors. O-san and others’ use of the term foreigners in a derogatory manner, however, touches on a darker part of Japanese history—when fake news spurred real deaths by the thousands.

The Mob Mentality

Around noon on Sept.1, 1923, a 7.9-magnitude earthquake tore through the greater Tokyo region, also known as Kantō. There were 114 reported quakes that struck Kantō before and after the major tremor; combined, they destroyed buildings, sparked fires that reduced wooded infrastructure to cinder, and ultimately claimed an estimated 100,000 to 160,000 lives.

Included in that count, however, were 6,000 Korean migrants living in Tokyo and Kanagawa. Their deaths came not from the quake directly, but from the brutal hands of mobs acting on misinformation. An article (paywall) on the Kantō earthquake and Korean massacre by Sonia Ryang, a professor of Asian studies at Rice University, details the mayhem days after the quake and pieces together brutal accounts from Japanese vigilante groups.

After the quake, newspapers shut down. Entire neighborhoods became scorched earth. By 2pm local time on Sept. 2, the government had declared martial law. Without the ability to distribute newspapers, local papers and individuals began printing and posting wall-posters and bills to street corners. At the time, television was not a widespread commodity, and it would be two years until public radio would come to Tokyo. Residents read the posted bills to make sense of the devastation. Often, these bills propagated rumors that Koreans were either directly responsibly for the damage, or were taking advantage of it by acting violently in its wake.

In The Origins of the Korean Community in Japan, Michale Weiner writes that makeshift posters and bills argued for the establishment of a jikeidan, or vigilante group. Citizens inspired by those writings began arming themselves with bamboo spears, swords, and other weapons. They staged checkpoints to interrogate passing individuals about their ethnicity. Upon discovering Koreans, they would execute them.

The jikeidan‘s mob violence gained surprising support from the Japanese military. Gotō Fumio, chief of the bureau of police affairs of Japan’s home ministry, sent a message via courier that was relayed to the prefectural governor. It ordered that “firm measures” be taken:

“There are organized groups of Korean extremists taking advantage of the disaster in Tokyo… [some] have been seen carrying bombs, spreading oil and setting fires… [We] request that you increase secret surveillance in all areas and take firm measures in dealing with the activities of Koreans.”

— quote from The Origins of Korean Community in Japan, 1910-1923 by Michael Weiner.

By 5pm that evening, the rumors had intensified. The Shiba Mita police reported posted bills stating “3,000 Koreans are looting and destroying Yokohama… and coming towards the capital.” By 6:30pm, a mob in Shiba Takanawa had produce 47 Koreans, who were swiftly arrested by Tokyo police. The police relocated them to a camp in nearby Chiba with other Koreans relocated from Tokyo.

According to Ryang’s research, one cadet officer witnessed a train full of quake survivors arriving at a train station in east Tokyo. The police dragged all the Koreans off the train and shot them on sight, while chants of “long live the emperor,” and “kill all Koreans” could be heard from the train cars.

In another account from the other side of Tokyo, Japanese citizen Fukushima Zotaro saw seven Korean men tied up in a line. One of them protested as a Japanese soldier took a sword to his head: “You pigs go to hell.” Witnesses turned their heads as 10 soldiers executed the men.

Vigilante mobs, with the support of the military police, continued killing Koreans until Fumio ordered police to distribute 30,000 leaflets telling the groups to stop the violence. By Sept. 4, the mobs stopped.

Why Koreans?

Academics still debate why Koreans became the targets of violence in the wake of the Kantō earthquake. Studies point to economic tensions between the Japanese working class and migrant populations, as well as political perception suppressing socialist values more commonly shared by Koreans at the time. Psychiatrists portray the Japanese as seeking release from their suffering by scapegoating Koreans for the disaster itself. Analysis is made all the more difficult by Japan’s own reluctance to acknowledge the scope of the massacre (paywall).

Not to be overlooked, however, is a larger history of antagonism between the two nations. In 1910, Japan annexed Korea as a Japanese colony, part of the construction of a vast imperial presence in east and southeast Asia. As reported by the CIA (pdf), the Japanese empire’s so-called “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” sold itself as the salvation of Asia, engaging in an ideological “holy war” under the slogan hakkō ichiu (“all the world under one roof”). The theory was that if everyone accepted Japanese values, technology, and culture, the region would be able to withstand western imperialism. This ideology, while based on unity, also framed the Japanese as superior to Koreans, Chinese, and members of other colonized nations. Even Koreans residing in Tokyo were considered outsiders and inferior to the Japanese empire and its citizens.

Today, these ethnic politics still play out. Despite major democratic reforms after World War II, the path to citizenship in Japan relies heavily on ethnicity; it is known as jus sanguinis, or “citizenship by blood.” To become a citizen through naturalization requires a significant amount of paperwork. People are only eligible after the age of 20 and if they can prove five years of legal residency. Birthright does not guarantee citizenship, meaning Koreans born in Tokyo still need to apply. This perpetuates a sense of the Japanese versus the foreign “other.”

These days, when false rumors circulate, governments and news agencies are quick to react. Twitter and other social media feeds have supplanted the bill postings of previous centuries, but the ability to verify accounts and see through the panic is easier. Government crackdown on fake news in Japan is swift and appears effective. Still, after the 2018 Osaka earthquake, many tweets used the word gaijin, meaning “outsider” or “foreigner.” Whether makeshift posters in the 1923 or fake-news retweets in 2018, the racial bias remains just below the surface.