The US farm bill could endanger poor American kids for decades

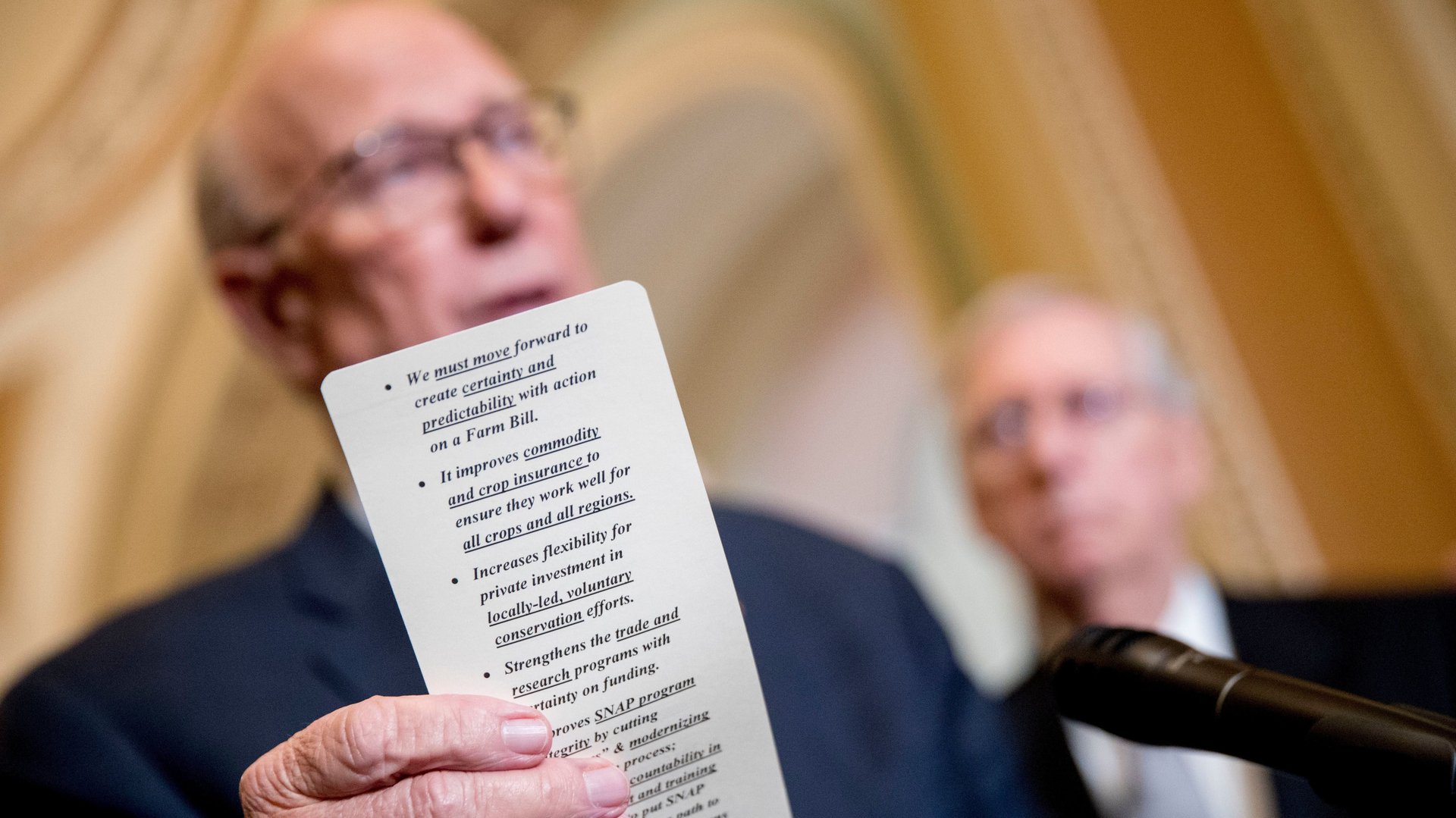

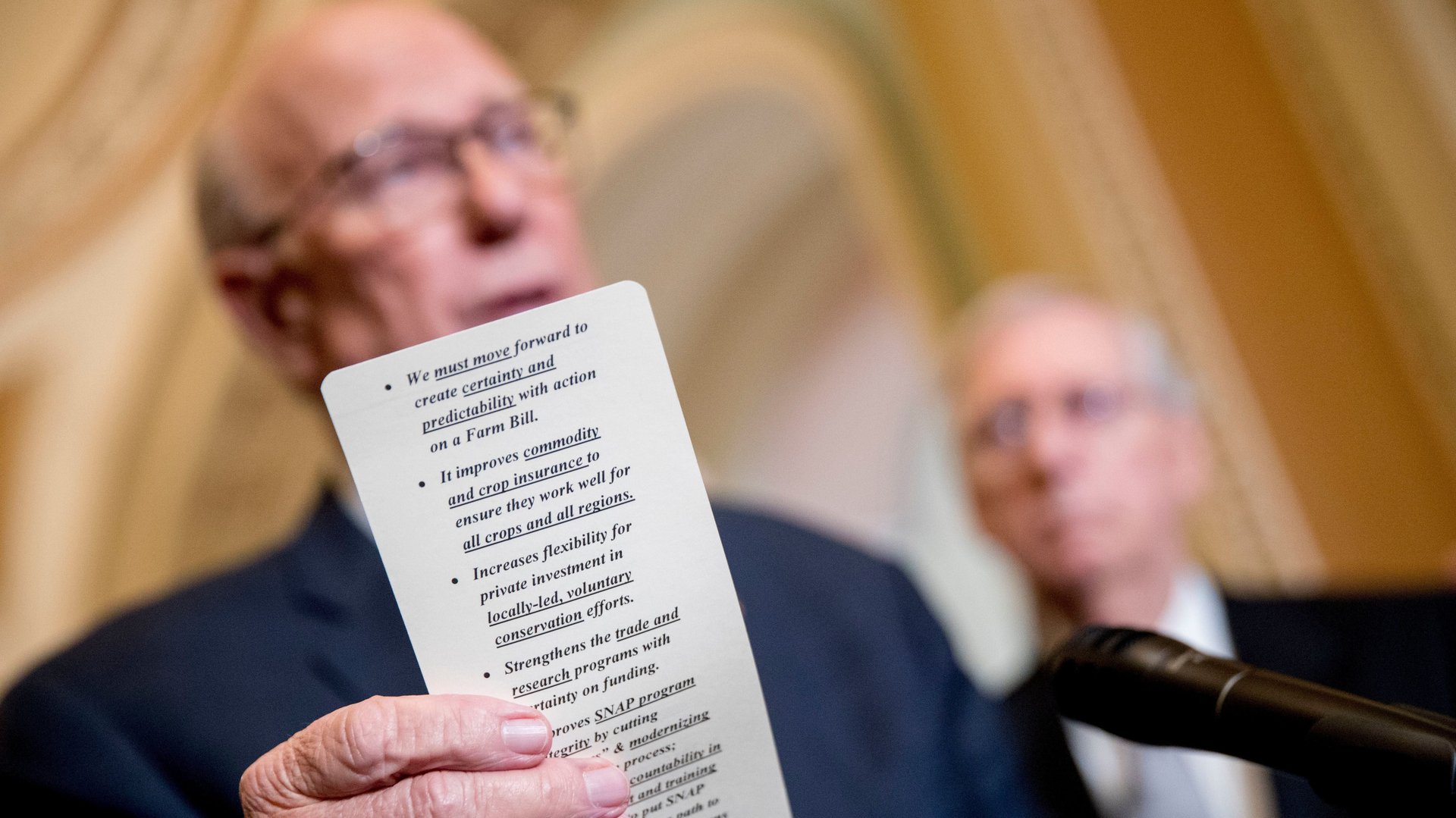

The US Senate has passed the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, its version of the $428-billion farm bill, clearing the way to reconcile it with the House plan. But the two versions of the sweeping agriculture and nutrition legislation seem irreconcilable.

The US Senate has passed the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, its version of the $428-billion farm bill, clearing the way to reconcile it with the House plan. But the two versions of the sweeping agriculture and nutrition legislation seem irreconcilable.

The House version, passed mostly along party lines in May, deals a blow to food stamps, farm subsidies and conservation funding. The Senate’s bipartisan version, passed yesterday (June 28), mostly preserves the status quo on food stamps and other nutrition subsidies. Experts warn that the stakes are high—the health and development potential of a quarter of a million under-privileged American children.

What is the farm bill?

Farm legislation renewed every five years governs an array of federal agricultural and food programs, including domestic nutrition assistance like SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, once called food stamps).

This year’s debate calls the existing structure of SNAP–whose recipients are mostly children, working parents, elderly Americans, and people with disabilities–into question. The House version would eliminate the provision known as Broad Based Community Eligibility, which allows working families with low-wage jobs to phase out of SNAP assistance, with state oversight.

That’s important because it might prevent low-income families from being able to afford care for their children at home and also because children in families receiving SNAP benefits are automatically certified to receive free school meals. This means that these children could lose access to food both at home and at school, directly contributing to an increase in childhood hunger and food insecurity among low-income households.

The Senate bill would reauthorize SNAP and related nutrition programs through 2023 while making several changes to those programs, including authorizing more funding for state-level pilot projects to employ and re-train recipients. Under the House version, adult recipients will be required to work or participate in a training program for 20 hours a week to receive benefits, or risk being kicked out of SNAP for one to three years.

The impact of hunger and food insecurity on kids

Food insecurity is a public health problem in the United States. According to the US Department of Agriculture, there were 3.1 million households where children and adults were food insecure in 2016. Of those households, most children still had access to enough food, and the adults bore the brunt of the low food security–but in 298,000 households, one or more of the children didn’t have enough to eat and had to miss meals at some point.

Household food insecurity has a significant impact the health and development of young children. It’s been shown to increase hospitalizations, poor health, iron deficiency, and behavior problems like aggression, anxiety, depression, and ADHD.

How SNAP helps poor and under-fed kids

SNAP plays an important role in countering these effects. it’s the main avenue to help poor and food-insecure Americans. The program disproportionately helps single moms and children: In 2016, 19 million children received SNAP each month, accounting for 44% of all participants.

Coming out of the massive welfare reform of the 1990s, this support became especially important. “For many low-income families, SNAP is the last line of defense,” says Lisa Davis, the senior director of the No Kid Hungry Campaign.

A study of SNAP assistance conducted by the Obama administration’s Council of Economic Advisers in 2015 found the program highly effective at reducing food insecurity and led to long-term improvements in health, academic achievements, and economic self-sufficiency. It showed that, among households who receive SNAP, food insecurity rates in 2014 were up to 30% lower than they otherwise would be.

That’s especially important for pregnant moms. Receiving food stamps during pregnancy reduces incidence of low birth-weight, and among adults who grew up in disadvantaged households, access to SNAP either in utero and during early childhood led to a higher likelihood of high-school graduation rates, improvements in overall health and economic self-sufficiency among women, a lower likelihood of obesity, and a significant reduction in conditions associated with heart disease and diabetes.

“We can invest in these children now through SNAP, and it’s probably one of the smartest investments we can make,” Davis says. “Or we’ll be paying later in terms of higher healthcare costs, poor educational outcomes, and a less competitive workforce—it’s pay now or pay later.”