Banning abortion does not make abortion go away

Banning abortion does not make abortion go away. Women who have the means to travel, or the desperation to go underground, have always found a way, and their organizing power ultimately made abortion a constitutional right in the United States. Today, women should keep that history in mind as they prepare for the next chapter in this fight.

Banning abortion does not make abortion go away. Women who have the means to travel, or the desperation to go underground, have always found a way, and their organizing power ultimately made abortion a constitutional right in the United States. Today, women should keep that history in mind as they prepare for the next chapter in this fight.

This week, US Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his plans to retire. Kennedy has long been the Court’s swing vote on issues like abortion. If president Donald Trump is able to appoint an anti-choice judge (which he has vowed to do), the cases that established abortion rights, such as Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood vs. Casey will face immense challenges, and could potentially be overturned as soon as next year. It’s a terrifying and overwhelming prospect.

Abortion has been a fact of life throughout our history. The first recorded mention of the practice dates back (pdf) to 1550 BCE. The first recorded law against abortion comes from the 11th Century BCE Code of Assura, proscribing the death penalty for women who had abortions without their husband’s permission. That women have fought successfully in many places for the lawful right to decide for themselves whether or not they want to keep a pregnancy is a reminder that as bad as things have been, even when they have been at their very worst, even when things are impossible, women have prevailed.

In America’s early years, there were no laws prohibiting abortion so long as it occurred before the “quickening”—the moment when the woman started to feel the fetus move in her stomach and it was considered to be alive. Herbal remedies such as the seeds of the peacock flower and cotton root bark were often used to end pregnancies. Manual procedures—inserting instruments into the uterus to induce miscarriage—were rare, but still occurred. These methods were traditionally administered by physicians and midwives.

It wasn’t until the mid-1880s that US states began criminalizing abortion. These bans often had less to do with a belief in life beginning at conception than they did with a fear that women might poison themselves, doctors might have to compete with unlicensed midwives for patients, and as a result of xenophobia and racism. With the arrival of new immigrants, and with black people freed from slavery, some feared that if Anglo-Saxon women were allowed to have abortions, white people would soon be outnumbered.

When abortion was banned in the US, much as elsewhere in the world, it didn’t go away, it just went underground. Sometimes it was safe, a lot of the time it was not. Those unable to find a doctor or a midwife who would give secretly them an abortion —which was not always a safe option either— often relied on self-inducing with dangerous and unreliable methods like patent medicines featuring not so subtle “will cause miscarriage in pregnant women” warnings, knitting needles, coat hangers, or falls down stairs. In 1930, illegal abortion was listed as the cause of death for over 2,700 women in the United States. In fact, the risk of an unsafe abortion continues to stalk women globally: Last year the World Health Organization estimated that nearly half of the 56 million abortions given worldwide every year are unsafe. Experts say that US funding cuts under Trump are likely to exacerbate the situation.

The abortion ban put more women at risk. But it also gave rise to the first outspoken abortion advocates: fierce and formidable men and women who fought to restore the right of a women to choose.

One of those women was Natalina Maria Vittoria Garaventa—nicknamed “Dolly” on account of her small size—who lived in Hoboken, New Jersey, 100 years ago. Dolly ran a saloon during Prohibition, got arrested by chaining herself to fences protesting for the right of women to vote, and was a Democratic Ward Leader before women even gained that right.

She was also a midwife who performed illegal abortions for those in need of one. And she had a son. His name was Frank Sinatra.

“Dolly, my mother, was a powerful force and dedicated worker in the political arena,” Sinatra is quoted as saying in the book Living the Revolution by Jennifer Guglielmo. “She was out there fighting for women’s rights before women even knew they should have them.”

It was a time when things seemed impossible, Dolly Sinatra persevered and she made them possible. She was to be among the first of many women to fight this fight.

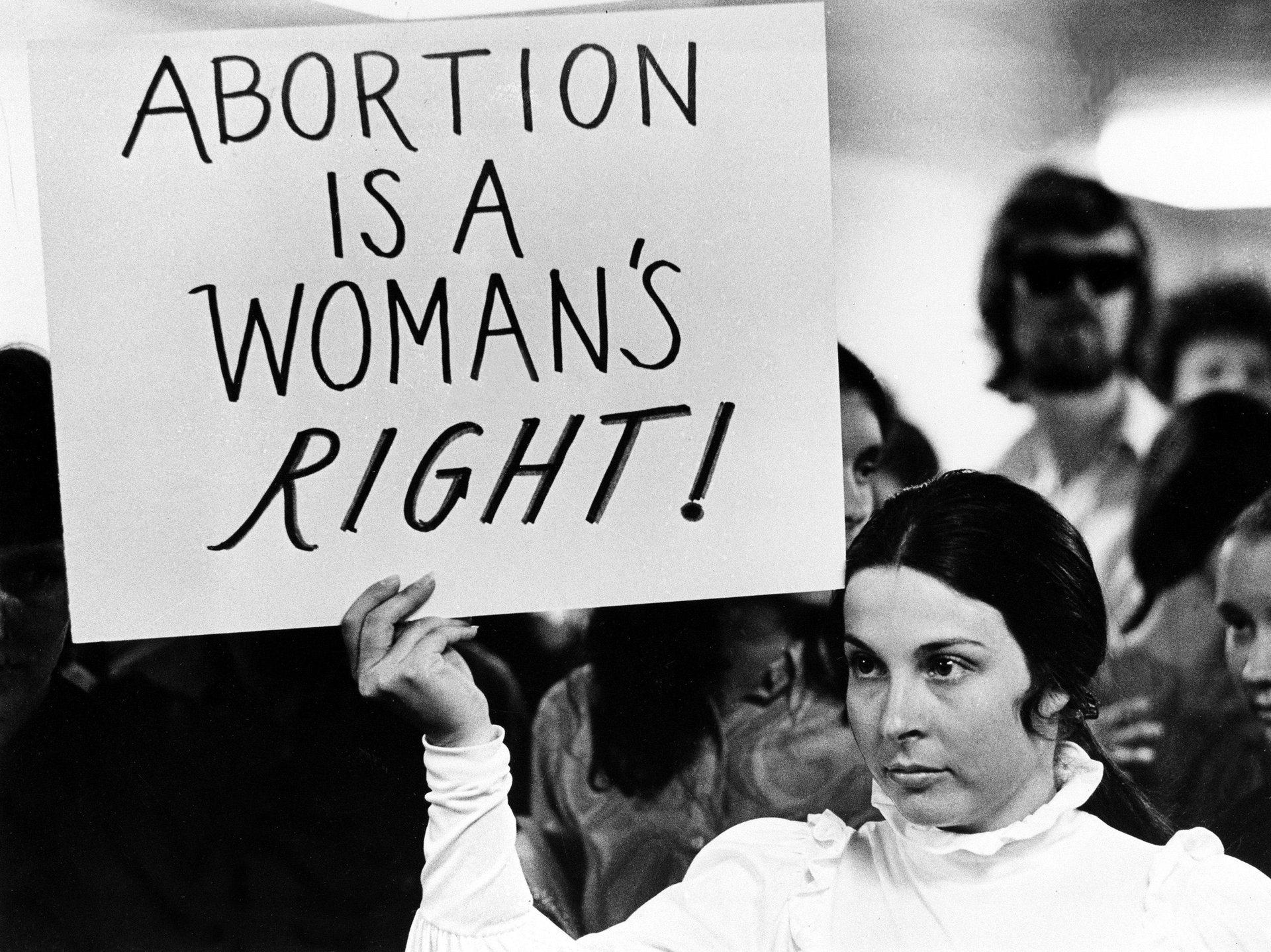

The women’s liberation movement in the 1960s picked up that baton, as women agitated for the right to safe abortion. In the US, from 1967 up until the passage of Roe vs. Wade in 1973, one-third of the states passed laws legalizing abortion. Where it remained illegal, women took things into their own hands.

From 1969 to 1973, the Chicago-based Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation—better known as the Jane Collective—helped over 11,000 women have abortions before Roe v. Wade compelled states to legalize them. Though they had initially intended to connect women with doctors who would perform abortions in secret, they eventually learned how to perform them themselves for far cheaper rates than doctors were charging. It was a risk, of course. They didn’t have medical licenses. They were volunteers who simply believed deeply in reproductive rights. But not one death was ever connected to the collective in the years it was active.

Around that same time, a man named Harvey Karman invented a device he called the Karman Cannula, meant to be a safer and more gentle way to perform early abortions through a process called “menstrual extraction.” This device and process was later modified and improved by Lorraine Rothman, a member of a women’s reproductive health self-help group in California. She and another member of her group, Carol Downey, began touting the device as a way women could perform abortions on each other, safely. They encouraged women to form self-help groups themselves to learn how to do this, and also to give themselves regular cervical exams.

The process, also called “menstrual regulation,” spread worldwide and is popular in places where abortion is illegal, like Bangladesh. Because it’s touted as a way to control the menstrual cycle rather than a form of abortion, practitioners are able to skirt the law.

In 1989, when the Supreme Court was about to hear Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, a case that potentially could have reversed Roe v. Wade, a group of women including Rothman, created a video encouraging women to form their own “self-help” groups and learn how to perform menstrual extraction on each other as a way of preserving abortion rights.

The letter advertising the video read:

“Won’t it be great to have the Supreme Court and state legislators get the news that women are showing this film openly and defiantly in living rooms, rented halls, or at your regularly scheduled meeting…The message we want to send to them is simple—there is NO GOING BACK. … Women have the technology of abortion, and will share this technology so that, if necessary, ‘underground railways’ can be organized.”

Even with legal abortion in the United States, people have still had to organize to make sure it is safe and available to all who need it. In the face of costly procedures, they have set up abortion funds for those in need. In the face of angry and often violent anti-choice protesters, they have bravely volunteered as clinic escorts. Couples have shared their experiences despite the stigma they face, and female politicians have shared their decision to have an abortion in the face of death threats.

Should the court decide to overturn Roe v. Wade, women will—like those before them, like those living in countries without abortion now—find a way. We will organize, we will raise money to help those in states where it is illegal to travel to states where it is, and if necessary we will learn these procedures ourselves. We shouldn’t have to. This shouldn’t be something we should even have to consider. But if history has taught us anything, it’s that we know how to fight back.

This article is part of Quartz Ideas, our home for bold arguments and big thinkers.