This brain “blackout” is the reason you get migraines

Researchers have identified the electrical activity specific to the start of migraines and demonstrated a way to stop it in animal experiments.

Researchers have identified the electrical activity specific to the start of migraines and demonstrated a way to stop it in animal experiments.

“Seizures and migraines are two very different states of the brain,” says Steven J. Schiff, professor of engineering in the departments of neurosurgery, engineering science and mechanics, and physics at Penn State.

“We found that the spreading depolarization, also called spreading depression, seen in migraines is a fundamental biophysical phenomenon and you can stop it with electrical current. Strangely, it is the opposite direction of electrical current used to turn off seizures,” Schiff says.

The researchers have not cured migraines, but they’re closer to understanding the mechanism in the brain that causes the start, or auras, of these headaches, which affect about 10% of men and 22% of women, according to the Center for Disease Control.

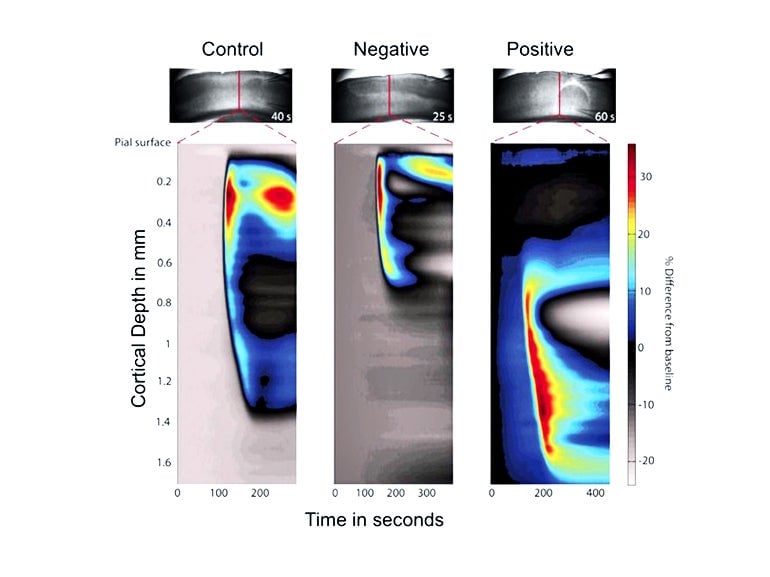

Carrying out experiments motivated by computational models of the biophysics of spreading depolarization, the researchers successfully demonstrated the modulation, suppression, and prevention of spreading depolarization in rat brain slices.

“The electrical activity in the brain causing the aura is like a rolling blackout,” says Andrew J. Whalen, postdoctoral scholar at the university’s Center for Neural Engineering. “It’s not just a single cell, but a chain reaction that moves across the brain causing swelling, and it takes people a while to recover.”

Many migraine sufferers first experience this visual aura before the headache begins. Schiff and his team targeted the electrical activity that causes the aura as it is fundamental in starting the migraine.

Researchers know that changing the salt concentration in the brain can alter the electrical processes of the brain. By altering the potassium concentrations in the brain, the researchers could trigger spreading depolarization.

The brain cells involved have a central body called the soma and a long, antenna-like arm called the dendrite. The two ends allow the researchers to polarize the cells with an electrical current—positive charges accumulate at one end and negative charges accumulate at the other. This allows them to use an electrical current to try to modulate brain cell activity.

“We thought that if we stopped the initial phase, the aura, we would stop the rest,” says Schiff. “We finally figured out that the charge necessary to stop the spreading depression was opposite to what we assumed. Once we chose the opposite charge, the progression of the phenomena stopped. This all made sense in the end, since seizures and migraines start at opposite ends of the brain cells.”

The researchers were able to use a positive charge to stop the spreading polarization. Imaging of the rat brain slices shows the migraine activity moving deeper into the brain where it can no longer propagate, effectively ending the episode.

“We came up with a biophysical understanding and it applies to the fundamental physiology of the aura, and we can make it worse with one current and we can make it better with the opposite current,” says Schiff.

Applying polarization such as this can be safely done in the human brain, and this strategy can be tested in clinical trials with migraine sufferers. However, the full migraine experienced by patients becomes more complicated after the initial aura.

“One wants to be able to fix the brain so that it is not susceptible to migraines or seizures, not to have to control migraines or spreading depression once it starts,” says Bruce J. Gluckman, professor of engineering science and mechanics, neurosurgery, and bioengineering and associate director of the Center for Neural Engineering. “For now, this is a fundamental result that moves us closer to being able to intervene in an important way for this condition.”

The research appears in Science Reports.

Researchers from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China; Penn State; and Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany also contributed to the work.

The US-German collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience program of the National Institutes of Health; the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; and the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative supported this work. The researchers have filed for a provisional patent on this work.

Source: Penn State

This article was originally published in Futurity. Edits have been made to this republication. It has been republished under the Attribution 4.0 International license.