The world needs a rocket tax to solve the “Gravity” space junk problem

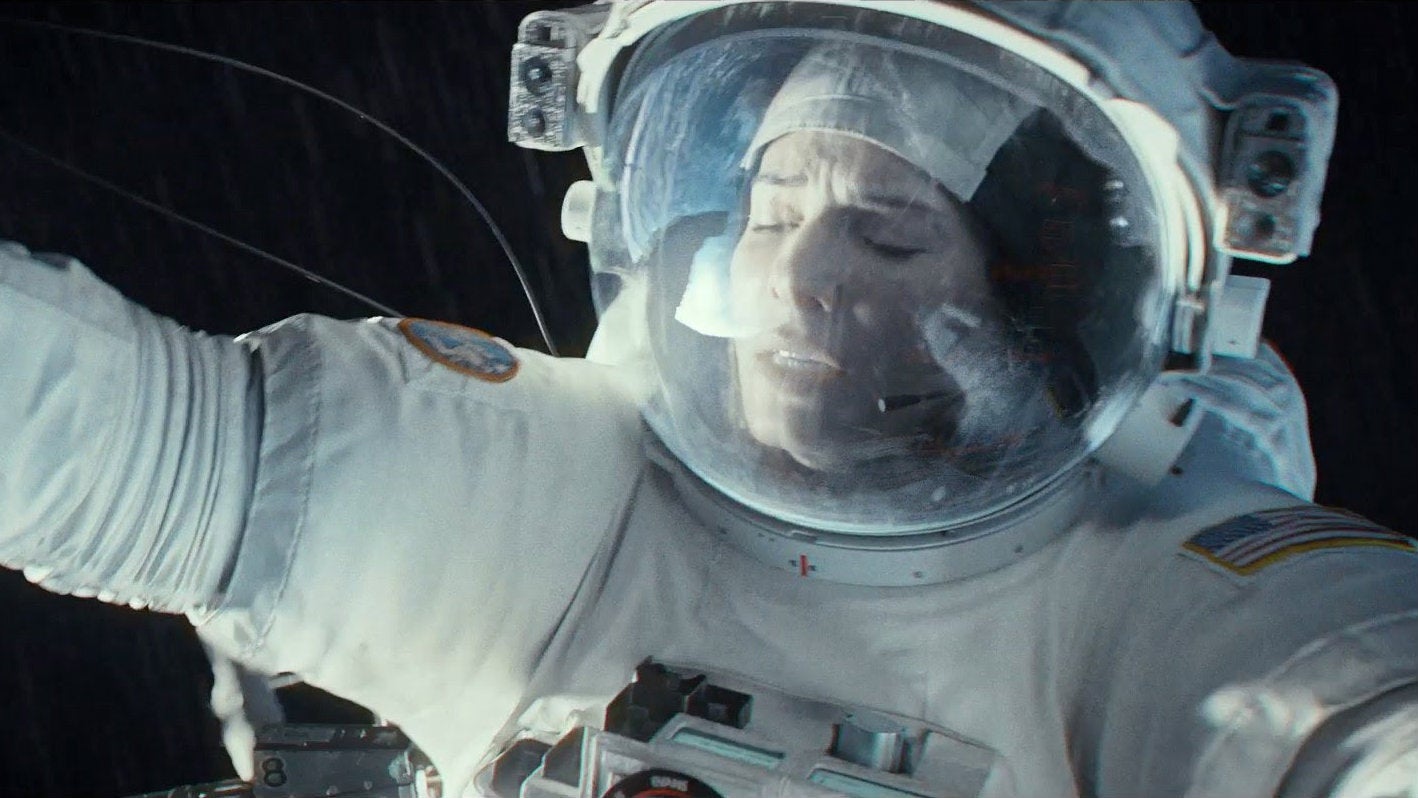

Alfonso Cuarón’s space adventure Gravity debuted this weekend to record-setting box office numbers, as audiences flocked to see the tale of two US astronauts (played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney) who are threatened by a cloud of orbital debris.

Alfonso Cuarón’s space adventure Gravity debuted this weekend to record-setting box office numbers, as audiences flocked to see the tale of two US astronauts (played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney) who are threatened by a cloud of orbital debris.

(Warning: mild spoilers ahead)

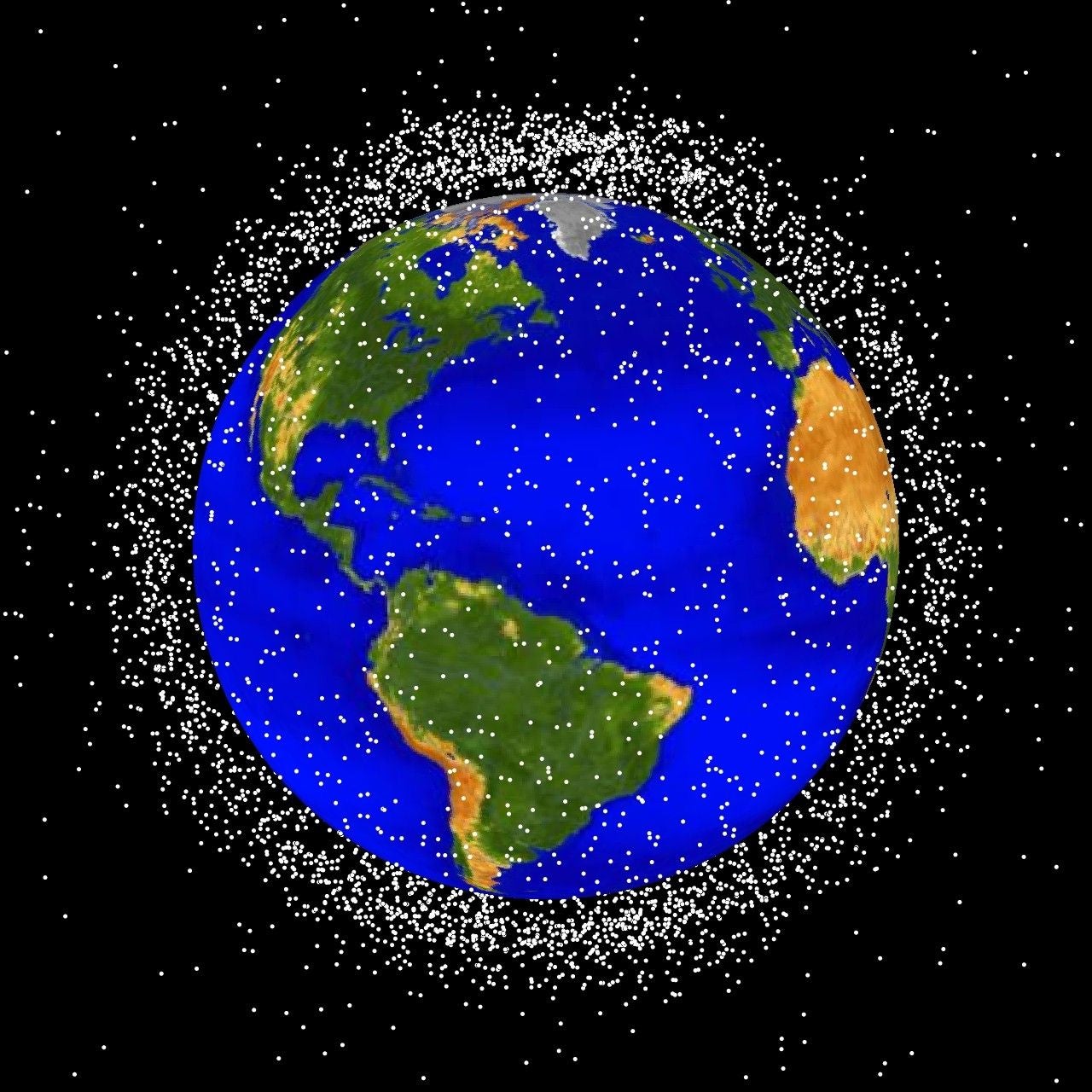

The scenario in the film—where Russia tests an anti-satellite weapon by blowing up one of their own satellites, creating a chain reaction of orbital destruction—is scarcely far-fetched, even though some of the subsequent plot points have been nit-picked. China did something very similar in 2007, blowing up an old weather satellite with a missile. Even without such drastic action, the amount of space debris is increasing quickly, endangering astronauts and commercial satellites, and it has reached a “tipping point” where Gravity-like chain reactions could occur.

Earlier this year, a group of economists from Indiana-Purdue University, the US Federal Communications Commission, and the US Naval Academy tried to figure out how to limit the potential damage to a satellite industry that is responsible for everything from internet communications to GPS networks, and which was worth some $170 billion in 2012.

“Orbital debris is space pollution,” the authors wrote in their study. “Space debris, an externality generated by expended launch vehicles and damaged satellites, reduces the realized value of space activities by increasing the probability of damaging existing satellites or other space vehicles.”

The study found that commercial satellite firms launch more satellites than is “socially desirable,” and they use launch technology that is more likely to create debris “because they only compare individual marginal benefits and costs of their technology choice and fail to take into account social benefits and costs.” That puts space debris squarely into the category of a “negative externality,” much like regular Earth-bound pollution, where the costs are unfairly borne by a third party—in this case just about everyone else on Earth.

One answer, they suggest, is a tax on satellite launches that could be used to pay for orbital clean-up—there are numerous theoretical schemes for getting rid of space junk, ranging from removing it with “janitor” satellites to blasting it with lasers. “However,” the authors conclude, “the practical problem of getting various economic actors to agree to a launch tax is daunting, to say the least.”