Your sweet tooth is displacing impoverished Brazilians, Cambodians and Africans

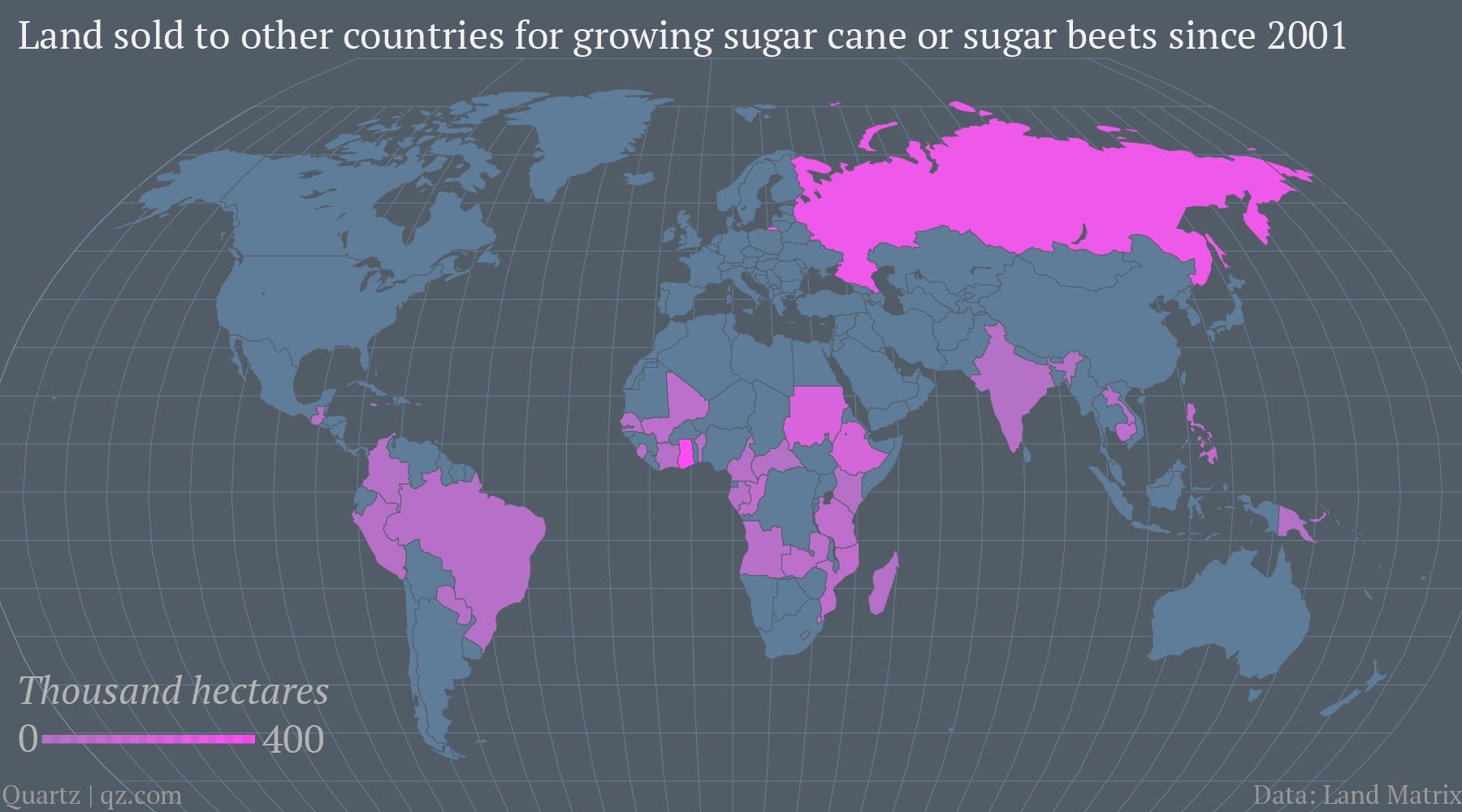

By 2020, the world will consume 25% more sugar than it does now. Where will it come from? At the moment, the biggest exporters of sugar are Brazil, Thailand, Australia and Guatemala. But that’s changing. Sugar cane uses more land than almost any other major agricultural commodity, which is fueling demand for more land. Of the 31 million hectares—about the size of Italy—currently used to produce sugar, around 15% (pdf, p.4) involves land purchased in 100 major deals inked since 2000, says Oxfam, a non-governmental organization. Often, these land sales are to foreign investors:

By 2020, the world will consume 25% more sugar than it does now. Where will it come from? At the moment, the biggest exporters of sugar are Brazil, Thailand, Australia and Guatemala. But that’s changing. Sugar cane uses more land than almost any other major agricultural commodity, which is fueling demand for more land. Of the 31 million hectares—about the size of Italy—currently used to produce sugar, around 15% (pdf, p.4) involves land purchased in 100 major deals inked since 2000, says Oxfam, a non-governmental organization. Often, these land sales are to foreign investors:

With land growing scarcer in big sugar-producing countries, agricultural companies are increasingly looking to poor countries with a lot of land and flimsy property laws, notes Oxfam’s Chris Jochnick. ”As pressure on the land is growing, inevitably you’re going to have more competition for the land and more land grabs,” he says, referring to large-scale land sales that ignore the claims of its residents and take place without their consultation, violate human rights, or occur without assessment of their environmental impact.

Villagers living on desirable sugar plantation land often face forced eviction and loss of their primary food source, either because they lose their farmland or the plantation diverts or pollutes water they depend on for their livelihood.

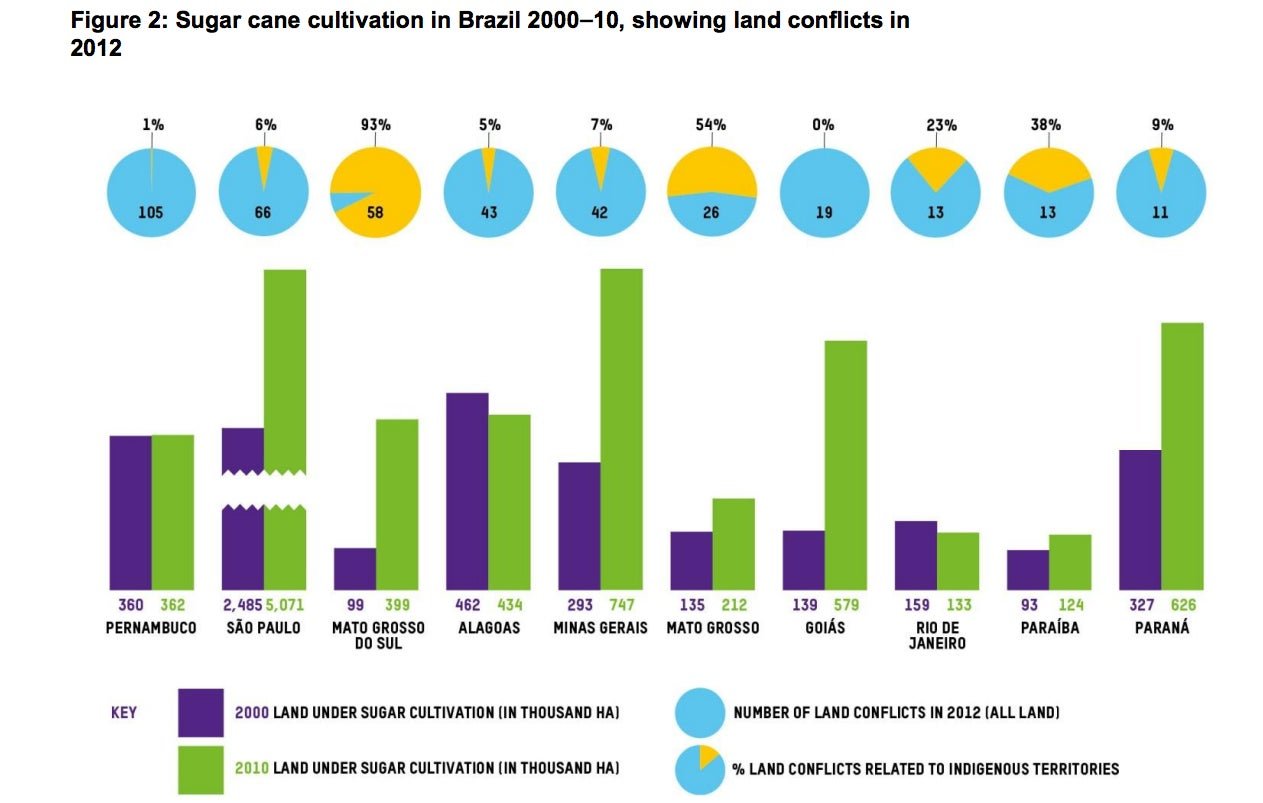

This is a growing problem in Brazil, where sugarcane is valued not only for its use as a sweetener, but also as ethanol, one of Brazil’s major fuel sources. The chart below compares the increase in Brazilian provinces’ sugarcane cultivation with the number of land disputes in 2012. It also looks at the incidence of those land conflicts affecting indigenous populations (who are more likely to lack land titles):

A similar trend is afflicting Cambodia, where sugarcane production now occupies twice the amount of land it did a decade ago. As the New York Times reports, the Khmer Rouge, Maoists who ruled Cambodia from 1975-9, destroyed almost all of Cambodia’s land titles. That means long-time residents can seldom prove that they own their land. Oxfam recounts how two companies majority-owned by Thai sugar giant Khon Kaen Sugar Co Ltd, which reportedly supplies London-based Tate & Lyle Sugars, is said to have launched a sugar plantation in 2006 that displaced 500 families in three villages from land they used for subsistence farming. At least 200 families say they were never consulted.

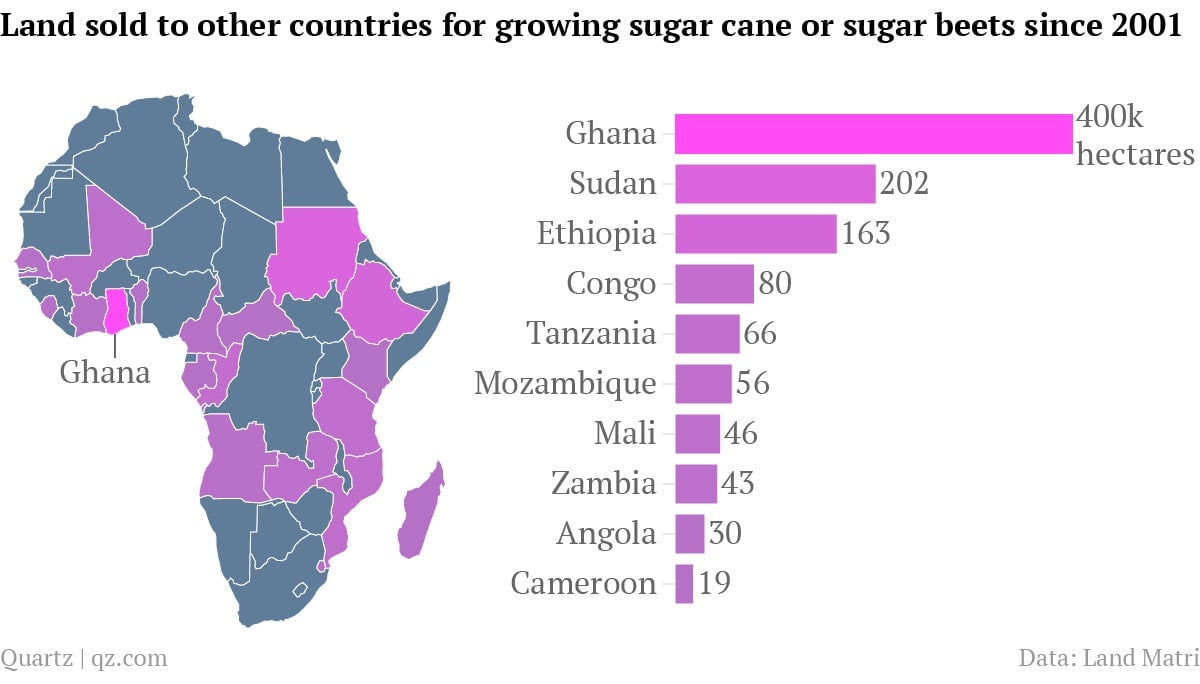

But things are particularly bad in Africa, says Oxfam’s Jochnick. ”Africa’s really the front line of land investment because so much land out there that hasn’t been titled,” he says, noting that more than half of the large-scale land deals since 2000 have taken place there. “It’s easier to deal with some of those governments because [their lack of] oversight [over] land tenure.” Here’s a look at how land sales to foreign owners have trended:

Take Sierra Leone, for instance, and a sugarcane project run by Swiss energy company Addax & Oryx Group. In 2009, Addax leased 44,000 hectares for 50 years for a project that will supply ethanol to Europe, funded by European Development Finance Institutions and the African Development Bank (the fact that it leased the land explains why it’s not on the map above). Research by the Oakland Institute, an NGO focused on land rights, found that villagers who were affected were largely unaware of project (pdf).

That probably explains why their rent is absurdly cheap; landowners receive $7.90 per hectare per year, compared with, for example, a cost of land of $570 per hectare (pdf, p.7) at a sugarcane plantation in Louisiana, in the southern US. One NGO found that Addax plans to bring in $53 million in annual revenue, meaning the company will pay just 0.7% of that $53 million (pdf, p.21) in rent each year to landowners, according to a report by a UK-based NGO. That’s a problem because the project occupies land on which villagers once raised cassava, rice and vegetables. While some villagers now have jobs at the plantation, many more now have no way of feeding themselves.

Sometimes the country’s own government is exploiting land claims. One of the most egregious examples involves Ethiopia’s ambition to become a major world sugar producer by 2025. It launched a 245,000 hectare state-run sugar plantation in the Omo river valley, a project that has so far entailed the involuntary resettlement (pdf, p.37) of tens of thousands of villagers, says Human Rights Watch, an NGO. Most of them are pastoral herders who need the land to raise their livestock. On top of that, the dam built to irrigate the state-run Ethiopian Sugar Corporation’s plantations has already stopped the annual flood that 170,000 farmers depend upon (pdf, p.5) for cultivation, says the Oakland Institute.

Of course, it’s easy for NGO researchers from the already industrialized West to glorify the “traditional” way of life. Critics of the Omo sugarcane project, said an Ethiopian government spokesperson, want to “drag Ethiopia back to the Stone Age.”

But there are more profitable ways to use agricultural land. ”Despite considerable investment by government, [raising animals] is consistently more profitable than either cotton or sugarcane farming while avoiding many of the environmental costs associated with large-scale irrigation projects,” wrote economists Roy Behnke and Carol Kerven in a recent report (pdf, p.7).

Governments of poor countries are probably flocking to sugar because it attracts foreign investment, especially from countries like India and China, which, along with the EU, are the world’s biggest sugar-guzzlers. Those countries are also less likely to shy away from projects that harm workers or the environment. Take for instance the dam planned for Ethiopia’s Omo sugar plantation projects. After failing to gain funding from the African Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, the government finally won a $500 million loan from China’s state-owned Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and a separate $500 million loan from China Development Bank. India’s development bank, meanwhile, loaned $640 million to the Ethiopian government’s sugar industry.

In an earlier chapter of sugar’s history, the hunt for slave labor drove the production of cheap sweets, taking sugar producers to Caribbean and South America. Today, the sugar industry’s profits are driven by cheap land, and the capital funding those investments.