Why emerging markets in Asia might be better off without all that cash they just lost

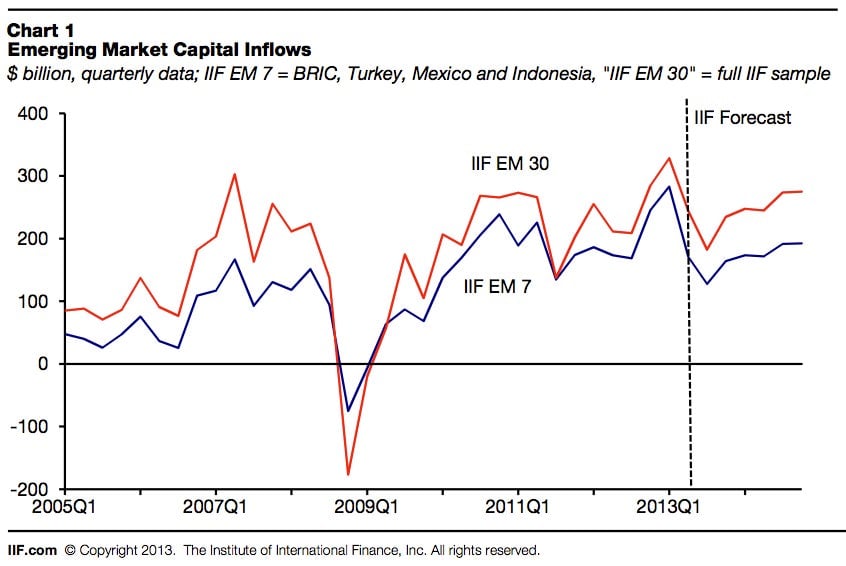

In response to signs that the US Federal Reserve could start winding down its massive stimulus program this year, investors pulled some $25.5 billion out of emerging market bond funds over 17 weeks, according to Barclays estimates. The flight of capital has reversed recently, but it’s not likely to all go back. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) now predicts that $153 billion fewer dollars will flow into emerging markets in 2013 than did in 2012, and total inflows of cash will fall further in 2014. In June, it had estimated that inflows in 2013 would fall just $70 billion.

In response to signs that the US Federal Reserve could start winding down its massive stimulus program this year, investors pulled some $25.5 billion out of emerging market bond funds over 17 weeks, according to Barclays estimates. The flight of capital has reversed recently, but it’s not likely to all go back. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) now predicts that $153 billion fewer dollars will flow into emerging markets in 2013 than did in 2012, and total inflows of cash will fall further in 2014. In June, it had estimated that inflows in 2013 would fall just $70 billion.

But slower investment in emerging markets could be good for them, and not just because the massive inflows of capital of recent years weren’t sustainable. If money moves back to advanced economies, creates jobs and fuels consumer demand, emerging economies will benefit too.

“We see the economic recovery in major economies as good, not bad, news for Asia as a whole. Growth is not a zero-sum game. Portfolio outflows do not always signal slower growth to come. We see reason for optimism as growth resumes in Europe (at least for now), accelerates in the US and Japan, and stabilises in China,” Standard Chartered analyst Marios Maratheftis wrote in a note published today (Oct. 7). “Simultaneous growth in major global economies looks more likely in the next 12-18 months than at any time since 2006,” he and his colleagues wrote.

That’s already showing up in trade data. Numbers from Containerized Trade Statistics show that, despite the loss of foreign cash, demand for emerging-market goods from the rest of the world is back. In August, exports in shipping containers grew 6.25% over August of the previous year—the sixth month in a row that there’s been a year-on-year increase.

A pullback in outside funding is not without its threats. Lending in emerging markets has ballooned as the world’s central banks pumped cheap money into the financial system. In some ways that’s reminiscent of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, when Asian countries became wildly overextended and indebted, writes Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Ajay Singh Kapur. If the money spigot stops flowing, it could be difficult for these countries and their businesses to refinance debts in the future. “It is not a good time to have worsening external balances that require USD financing, or indeed too much foreign debt, especially of the short-term variety, or an uncompetitive exchange rate in these periods,” he wrote last month.

Even so, the strongest emerging-market policymakers seem better prepared than they were the last time foreign investors gobbled up Asian debt. ”Most countries have followed cautious fiscal policies and avoided the build-up in public debt seen in many mature markets since the 2008 crisis,” explains IIF managing director Charles Collyns. That—in addition to better monetary policy and more cautious planning—should allow emerging markets to continue to grow despite the slowing tap of foreign funds.