A Berlin gathering for China’s Liu Xiaobo is a reminder of two very different 1989s

Exactly one year after the death in Chinese custody of his friend, dissident and Nobel peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, Liao Yiwu stood on the altar of Berlin’s Gethsemane church playing a new, melancholic musical piece for the flute entitled Liu Xiaobo’s Last Moments.

Exactly one year after the death in Chinese custody of his friend, dissident and Nobel peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, Liao Yiwu stood on the altar of Berlin’s Gethsemane church playing a new, melancholic musical piece for the flute entitled Liu Xiaobo’s Last Moments.

The piece was inspired by a phone conversation Liao had last year with Liu’s widow Liu Xia, who was kept under house arrest by Chinese authorities. “He [Liu Xiaobo] told me I had to get out of the country,” Liu told Liao. “In the end he stopped speaking—he just kicked his leg to show what he meant.”

Just days shy of the first anniversary of his death, Liu Xiaobo’s wish came true. Liu Xia arrived in Berlin ahead of a memorial service in the German capital attended by nearly 1,000 people. The event was both a long overdue public funeral for Liu—after his death on July 13, 2017, his body was hastily cremated and his ashes were scattered into the sea—and a mourning for the failure of China’s democracy movements.

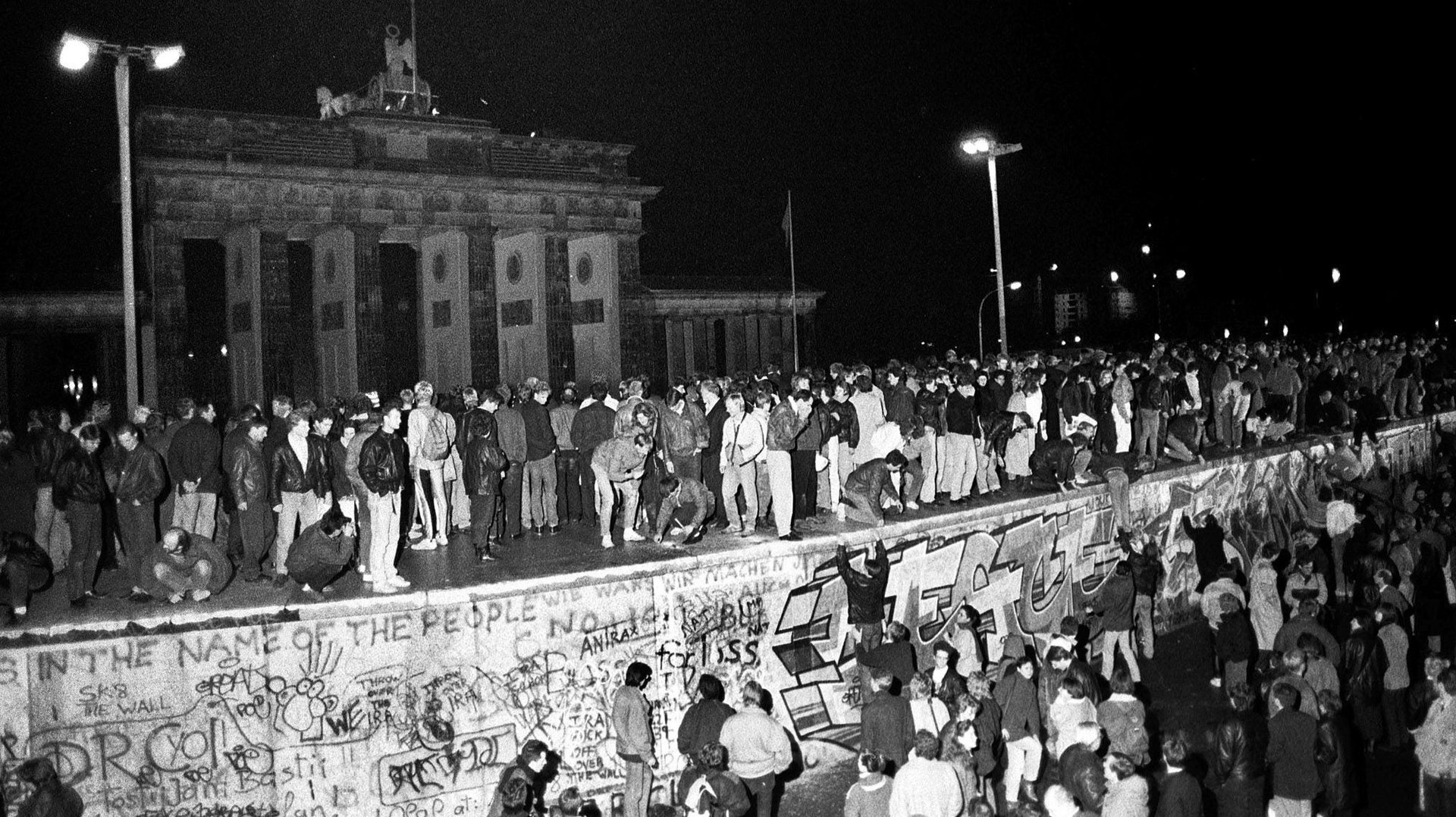

Held at historic Gethsemane Church, the memorial also drew a line between the historic events of 1989 in Beijing and Berlin, watershed years for both countries, but with starkly different legacies. The Tiananmen Square protests for democracy ended in bloodshed on June 4, have been followed by the harsh silencing of dissidents ever since, including from Liu Xiaobo, a key figure in the 1989 movement.

In Berlin, however, the Berlin Wall that had divided the country into East and West since 1961 came down that year, a victory for democracy in which the Gethsemane Church had a key part to play.

The Wall must go

Constructed between 1891 and 1893, the Gethsemane Church, or Gethsemanekirche in German, was designed by August Orth. An iconic piece of architecture of neo-Gothic brickwork facade, it was located in Prenzlauer Berg, which belonged to the former East Berlin, the Gethsemane Church was a key refuge for East German dissidents.

In early October 1989, a vigil was held at Gethsemane Church calling for the release of protesters arrested in Leipzig in the previous month. But the vigil ended in a violent clash with the police and many were arrested. In solidarity, thousands of people began attending services at the church every evening, and it became a center for opposition to the East German government.

On November 5, 1989, a day after the largest demonstration yet took place in the Alexanderplatz public square, and protests subsequently spread across the country, Rolf Reuter, senior musical director of the opera company Komische Oper, made a landmark speech. After conducting the state orchestra’s performance of Beethoven’s Third Symphony, he demanded, “The wall must go!” More demonstrations followed.

On November 9, the East German government decided on new travel regulations allowing East Berliners to cross the border more freely, set to take effect the next day. But an official mistakenly announced the changes were already in effect, prompting crowds to gather at the wall. They outnumbered the guards and eventually the passport checkpoints were abandoned. People began crossing the border and young people from both sides climbed the wall, cheering. The wall fell symbolically that day, though its demolition was officially completed in 1992.

The Berlin Wall of China

Certainly 1989 was a watershed year for China too—and one that shaped Liu Xiaobo’s decades of nonviolent activism for human rights. Liu was first jailed by Chinese authorities for his involvement in Tiananmen Square protests. Later he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his participation in writing Charter 08, a manifesto calling for democracy, and the elimination of one-party rule in China.

Organizers of Friday’s memorial service said China has been building its own Berlin Wall for decades by sending political and human rights activists to jail. Just one day after allowing Liu Xia to travel to Germany, the Chinese government sent Qin Yongmin, a leading pro-democracy campaigner and human rights activist, to jail for 13 years on the same charge for which Liu Xiaobo was convicted: subversion against the state.

And according to Tienchi Martin-Liao, one of the organizers of the memorial service and the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, Liu Xia decided not to attend the memorial service for the safety of her brother Liu Hui, who remains in China. Liao also said Liu was physically weak and needed further medical care.

Among those who paid their respects to Liu Xiaobo was singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann, a former East Germany dissident. According to Liao Yiwu, Biermann is a personal friend of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and was a key messenger in campaigning (unsuccessfully) for the release of Liu Xiaobo last year when his medical situation was disclosed, and in the successful release of Liu Xia. He shared the stage with American author and journalist Ian Johnson, who gave a speech about Liu.

At the service, Nobel literature laureate Herta Müller, who played a key role in nominating Liu Xiaobo for the Nobel peace prize, read poems written by Liu Xia in German. In remarks translated by Martin-Liao, she urged listeners not to forget those still imprisoned, and expressed the hope that one day the Chinese government “understands that people who hold different opinions are not threats to the government, but a crucial force for a better future.”