These charts give Trump perfect ammunition for bashing the EU

Today (July 25) Donald Trump is sitting down for what’s sure to be an interesting chat with Jean-Claude Juncker, who heads up the legislative commission of the European Union—the US president’s favorite punching bag of late.

Today (July 25) Donald Trump is sitting down for what’s sure to be an interesting chat with Jean-Claude Juncker, who heads up the legislative commission of the European Union—the US president’s favorite punching bag of late.

“You look at the euro, you look at what’s going on with the EU, and they are not doing what we are doing and we already have somewhat of a disadvantage,” Trump said in a July 20 interview with CNBC.

If Trump wants to back up that accusation at today’s meeting, he has a handy crib sheet in the form of a new report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The organization’s just-published report focuses on how the trade and capital imbalances between countries’ economies could destabilize the global economy. And as Kit Juckes, currency strategist at Société Générale, flags in a note today, the euro zone—particularly Germany and the Netherlands—are among the report’s biggest baddies.

Current account surpluses (meaning, the excess of savings over investment that lead countries to export way more than they import) are the chief way of measuring these imbalances. Running a surplus isn’t necessarily bad, say the report’s authors. A surplus can, for instance, better cushion countries to absorb economic shocks. On a global level, a current account surplus can help dish out capital to places where it will yield the most growth.

However, when major economies save a lot more than they invest for too long, they become less able to absorb economic shocks and waste wealth that should have have been invested more productively.

And that ultimately threatens global stability.

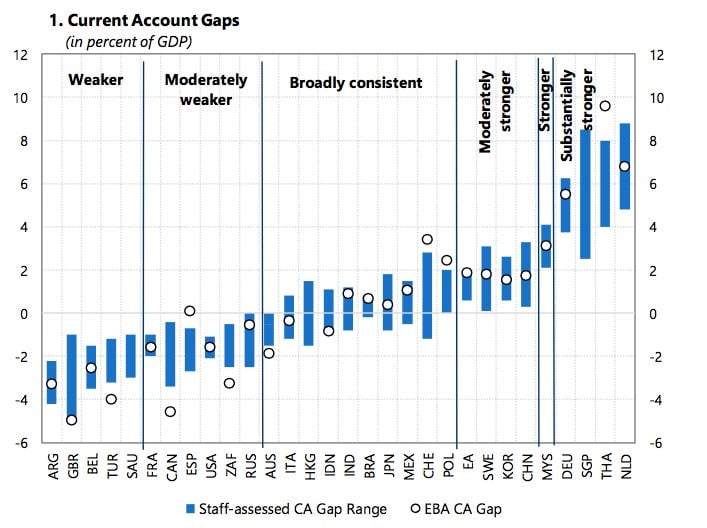

As it happens, among the biggest culprits running “higher than desirable balances” are in the euro zone—particularly Germany and the Netherlands. They were among only four major economies the IMF criticized for running current account surpluses “substantially stronger” than they should be (Thailand and Singapore were the other two). As for the euro zone as a whole, the IMF economists downgraded the currency union to “moderately stronger,” versus the 2017 report’s neutral rating. By comparison, the US’s external position is “moderately weaker.” Here’s how those countries stack up with the other two-dozen or so in the IMF’s analysis:

So how do Germany and the Netherlands run such mammoth current account surpluses? Currency is a big part of the answer; it’s the mechanism that restores balanced flows of trade and capital among countries. For instance, when a country runs a big trade deficit, the value of its currency should drop, making its exports competitive enough to shrink the gap.

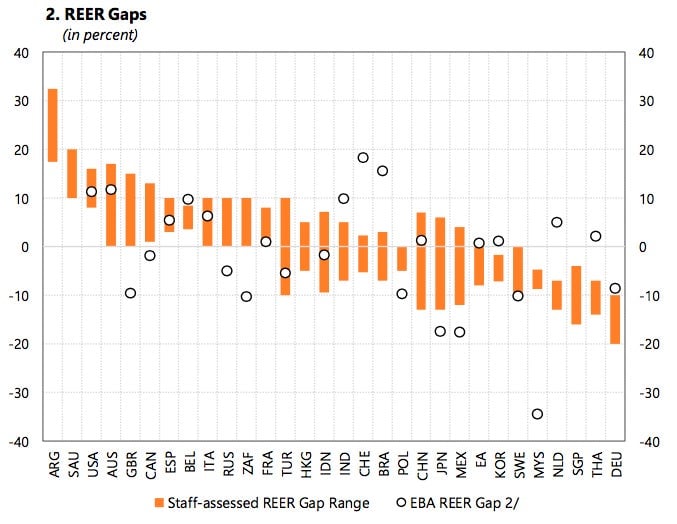

To analyze currency values, the IMF calculates the gap in a country’s real effective exchange rate—the inflation-adjusted value of the currency versus the currency values of its trade partners. A big REER gap means the currency is valued more than it needs to be to restore balance; a negative REER gap means it’s too cheap.

According to this analysis, the US dollar is around 12% overvalued, and the euro undervalued by about 4%, according to mid-range estimates. However, in Germany, the euro zone’s biggest economy, the euro is around 15% weaker than it should be.

So how do you fix these dangerous imbalances? As Juckes notes, Germany should up its fiscal spending and slash regulatory barriers to investment. Meanwhile, the US needs to rein in fiscal spending and boost the skills of its workforce. “That’s a bit ‘motherhood and apple pie’ but the US really doesn’t need late-cycle fiscal easing…,” writes Juckes, “and Germany doesn’t need a budget surplus and aging infrastructure.” Unfortunately for Trump, that means that raging against EU officials and threatening tariffs won’t do much unless he reverses some of his own policies.