Euro zone banks may need another fix of emergency funds. Will the ECB oblige?

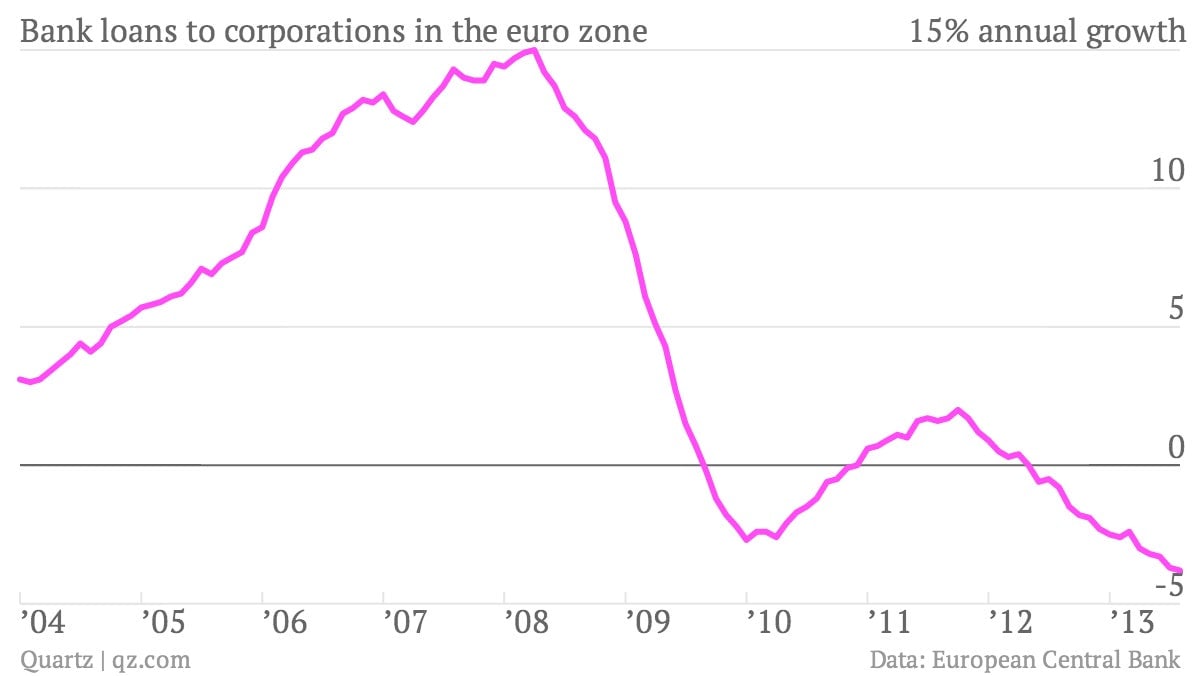

The euro zone’s economic ills, in a nutshell, derive from too much debt. Still, there are many blameless borrowers—particularly small businesses—that find it difficult to get credit as banks are preoccupied with nursing their own balance sheets back to health. Loans to euro-zone businesses, as detailed in the latest monthly bulletin (pdf) from the European Central Bank (ECB), are falling faster than ever.

The euro zone’s economic ills, in a nutshell, derive from too much debt. Still, there are many blameless borrowers—particularly small businesses—that find it difficult to get credit as banks are preoccupied with nursing their own balance sheets back to health. Loans to euro-zone businesses, as detailed in the latest monthly bulletin (pdf) from the European Central Bank (ECB), are falling faster than ever.

This, and the general shakiness that continues to stalk the euro zone’s banking system, is stoking talk about reviving an emergency liquidity program for the region’s lenders. In late 2011 and early 2012, the ECB doled out €1 trillion ($1.35 trillion) in three-year loans with a rock-bottom 1% interest rate in a program known as Long-Term Refinancing Operations. Hundreds of banks took the ECB up on its offer—although many, rather than using the funds to write more business loans, bought bonds and other securities in the hope of turning a quick profit.

Now, rumors of a new round of emergency liquidity injections are gathering steam. ”Nobody wants to have a liquidity accident standing between now and the recovery,” said ECB president Mario Draghi last week. Other ECB officials say they are in no hurry to pump up banks, but they are keeping all options open to support the region’s nascent economic recovery.

Complicating the apparent clamor for another round of injections is the fact that around two-thirds of the previous emergency loans have been repaid early, with banks keen to show that they can stand on their own (or at least appear to). But key interbank lending rates are creeping upwards, suggesting possible stress in bank funding markets.

Taper across the Atlantic

The debate over whether the ECB should inject more liquidity into banks is similar to the arguments about the eventual “taper” of bond purchases by the US Federal Reserve. Both the euro zone and US financial systems are still awash with liquidity pumped in by central banks, but the prospect of those excess funds eventually dwindling away makes markets nervous.

Many bankers say that weak demand for credit, not lack of liquidity, is what’s causing banks to lend less, and they are probably partly right. But given that European companies rely so heavily on bank loans for financing, many otherwise creditworthy firms are surely being turned away for loans, limiting their ability to grow. In the ECB’s latest bulletin, its researchers crunch the numbers on the correlation between GDP growth and bank lending. They find that growth in business lending lags overall GDP growth by about a year. Given the euro zone’s tepid, halting economic recovery, business loans won’t start to recover until next year at the earliest, the researchers conclude. In the meantime, the credit crunch grinds on.