Tech investors have found something even more addictive than social media

Digital addictions can’t compete with the real thing.

Digital addictions can’t compete with the real thing.

Juul Labs, valued at $15 billion, is one of the world’s largest fast-growing startups. It reached its sky-high valuation less than a year after spinning out of tobacco-turned-cannabis company Pax Labs, which was founded in 2007. It’s achieved that heady milestone several times faster than Facebook, Snap or Twitter with revenue growth topping 300% per year, according to the private equity research firm Pitchbook.

The company, which sells e-cigarettes that vaporize a flavored nicotine solution, is projected to generate $940 million in sales this year and controls 72% of tracked US e-cigarette market. The company has just started to sell outside beyond the US, into the $760 billion global market for tobacco products.

Investors are eager to get in on the market. While Silicon Valley’s venture capitalists have largely stayed away (generally due to rules against investing in “vice” such as drugs, guns, and alcohol at many venture-capital firms), the San Francisco-based company has raised about $2 billion from private-equity firms Tiger Global Management, Fidelity Investments, as well as the New York-based venture firm Evolution Corporate Advisors.

After all, Juul sells the most addictive legal substance on the market—nicotine. Harvard University reports that while 70% of smokers want to quit, only 3% manage to do so every year. The drugs works by tapping directly into the brain’s reward center: After smoking (or vaping), nicotine is carried from the lungs into the bloodstream and up to the brain. Once there, it triggers the release of dopamine, a naturally occurring chemical that lights up the brain’s pleasure centers. Every brief rush, however, soon brings an uncomfortable withdrawal. Concentration falters. Anxiety, headaches, and irritability may rise. Depression and sleeping problems can follow. To quell symptoms, users reach for more.

Juul adds a new twist to the traditional tobacco-smoking habit. Its rechargeable device uses an electrical element to heat the nicotine solution creating a tasty, easy-to-inhale aerosol cloud inhaled into the lungs. It comes in flavors such as mango, crème brûlée, mixed fruit, and “cool cucumber.” Light smokers, or even new users, may find themselves switching to e-cigarettes and consuming enough nicotine to equal a pack of cigarettes.

Sam, a 26-year-old analyst, is one of them. The year before switching to Juul, he was smoking six or seven cigarettes per day. Today, he’s quit smoking and vapes every day instead. He calls Juul “a radically more safe alternative” to smoking, even if he’s found the nicotine itself “incredibly addictive.”

“This is both a feature and a bug,” Sam wrote to Quartz. “It means Juul is far superior to other vapes when it comes to smoking cessation, but also more addictive itself. But that’s why it’s so effective.” Sam estimates his nicotine consumption is now far higher than before he quit smoking (about one “pod,” which holds the nicotine solution, every one to four days), but it’s a good deal for him, and society. Since the risk of health problems is dramatically lower, and he feels it’s easier to quit when he decides, the $15 or so he spends on Juul pods each month is “probably a small price to pay relative to the personal and societal benefits of smoking less,” he said.

That’s the argument that Juul itself is trying to push, according to James Monsees, co-founder and chief product officer of Juul. He says his company is replacing a deadly addiction with a safer habit. “Our goal is to make smoking obsolete,” Monsees told Quartz earlier this year. “The mission of the company is to eliminate cigarettes off the face of the earth.” It may be the first product with a chance of doing so. Many treatments to wean addicts off nicotine—gums, patches, pills, and sprays—only succeed for less than 20% of those who try them. Juul’s extraordinary popularity means it’s in a position to replace the cigarette, the first “very efficient and highly engineered drug delivery system” to enter mass-production.

Vaping, by delivering a tailored dose of nicotine, offers people an off-ramp from smoking, argues Monsees. Making a desirable product is part of that. Juul’s slick handheld metal vaping pens, playful flavors, and colorful advertising communicate the product as something you want, not something you need to quit. Pax’s products, before spinning Juul out, have been referred to as “the iPhone of vaporizers.”

Juul is rolling out features to give users control over how much, or little, nicotine they want to consume. Juul, like its competitor Philip Morris, which owns 130 cigarette brands and recently moved into vaping with IQOS, is racing to own the market as nicotine addicts chose a new delivery mechanism. “We want to do the right thing here,” Monsees said. “It’s absolutely necessary to capture as much of the market as appropriate.”

While dangers of smoking are severe—480,000 Americans die each year as a result of smoking, and the American Cancer Society estimates cigarettes will kill 1 billion people globally by the end of the century—the data (pdf) on the health effects of vaping are still limited. No scientific consensus exists on its long-term effects, and official government positions on the topic remain inconsistent. A 2018 report commissioned by the UK’s public health agency found (pdf) “vaping is at least 95% less harmful than smoking.” The US surgeon general still maintains e-cigarettes are “not safe“ for anyone under the age of 25 (when adolescent brains are still developing), and warns of evidence that vaping aerosols may not be as benign as it seems. Lung inflammation, DNA damage, and even lethal damage to cells have all been seen in lab tests.

But the risk of creating new nicotine users, especially among the young, must be weighed against the chance of reducing harm for existing smokers, David Abrams, a professor at New York University’s College of Global Public Health, argues. “There are adult lives at stake, too, and I think long-term use of nicotine, if decoupled from the toxins in cigarette smoke, would probably be much safer than heavy long-term use of alcohol and marijuana,” he told The New Yorker (paywall).

Juul users back up Abrams’ view: One blogger recounted his wife using vapes to wean herself off cigarettes, and then eventually quit vaping itself. A Twitter user claimed “as a 20-year cigarette smoker who was only able to quit now for 2 years by switching to E-cigarettes and stepping down nicotine levels from 22mg to 6 and soon to be 3 then finally zero I thank God for this technology. It has literally saved my life.”

Are the kids all right?

Public health officials concerned by Juul are weighing the risks for new young nicotine addicts. In July, Massachusetts announced it was investigating Juul’s advertising campaigns that appeared to specifically target young people. “Way too much of their product is ending up in the hands of young people and ending up in schools, today,” Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey said at a press conference at the time.

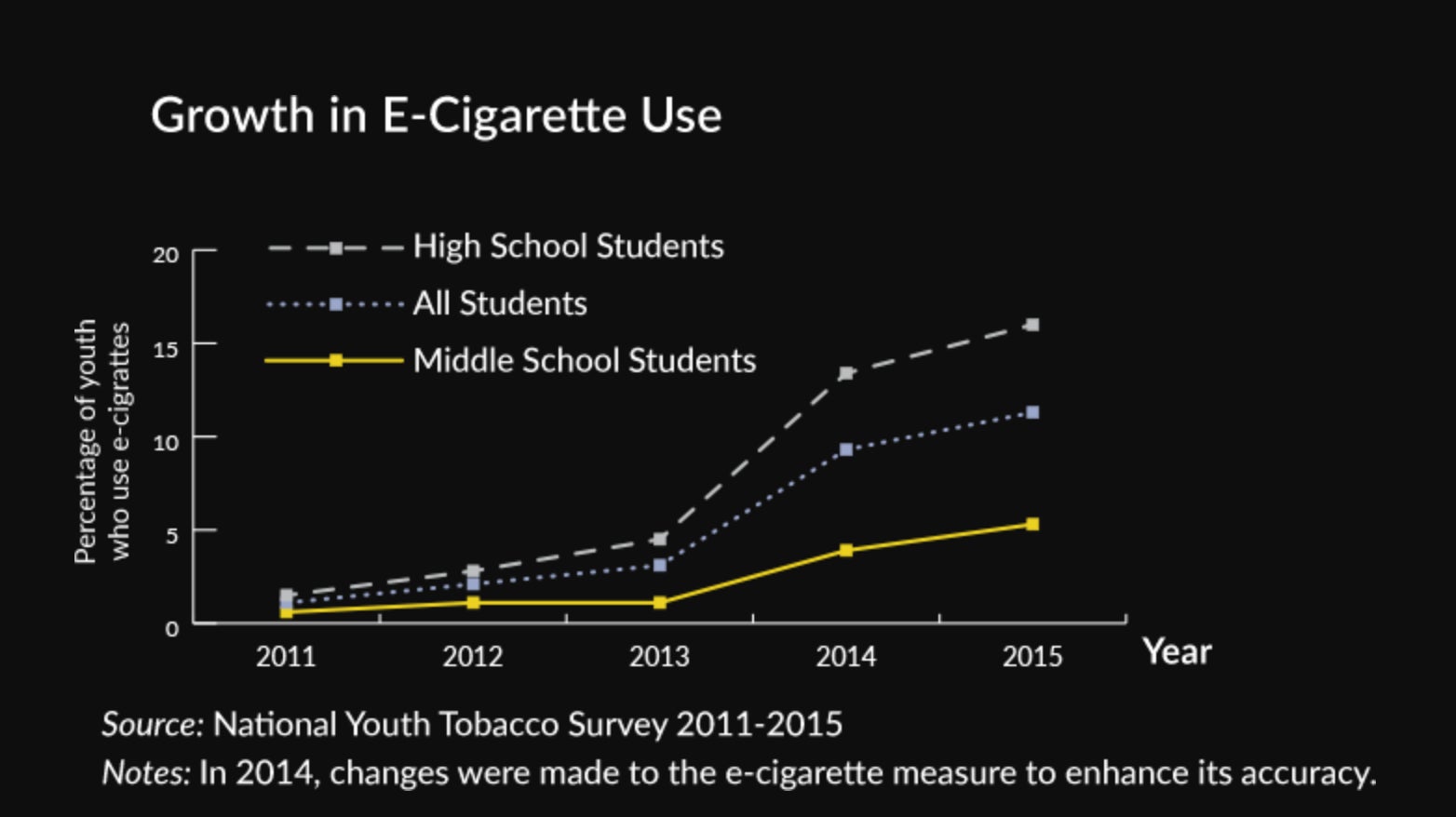

Vaping is now on the rise, especially among the young. Despite strict sales restrictions, the number of high school students using e-cigarettes within the prior month has soared 900% among high school students from 2011 to 2015, according to US health officials, and reached more than 3 million last year. For 18- to 24-year-olds, the single largest demographic of e-cigarette users, they are now more popular than conventional cigarettes.

In response, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cracked down on the sale of e-cigarettes and tobacco products to minors, and threatened to pull Juul’s product off the market. In October, the FDA carted away more than 1,000 documents in a surprise inspection of the company’s sales and marketing practices (Juul had voluntarily handed over 50,000 documents earlier in the year). Juul says it never markets directly to minors, and is spending $30 million ensuring its products stay out of their hands.

Monsees points to the company’s surveys showing almost none of its customers move from vaping to smoking cigarettes (which he calls an “inferior product”), and many drop cigarettes entirely. “No one wants a safer cigarette,” Monsees argues. “They want to move past it.” Juul surveyed 11,689 customers in the UK in July and found that 49.5% of users said they had stopped smoking cigarettes after switching to Juul’s vaping product, and only 0.3% non-smokers picked up cigarettes after using Juul.

Independent studies have yet to confirm whether Juul’s effect on youth smoking and its attempts to exclude underage users are not working. Om Malik, an investor at True Ventures, and former smoker, argues that Juul is using Silicon Valley growth tactics, including presences on social networks popular with younger people, like Snapchat and Instagram, to hawk products that will hook a younger generation. “Just because…the nicotine is delivered in specialist pods that fit in vape devices that resemble a cute USB stick—it doesn’t make the product less addictive. Or less evil,” Malik wrote earlier this year. “Any halfway decent person can see that tobacco & nicotine industries are driven by greed and have preyed on human frailty.”

The economics of addiction

There’s the crux of the issue: Can an ethical market exist for an addictive product? Some economists argue it cannot. Profits will always drive companies to look for new demand for its products, not just satisfy their existing users, creating a new class of dependents. Mark Kleiman, a public policy professor at New York University, has been helping governments design drug legalization policies for years, and recently told Quartz that most profits are made by a small number of heavy users. He said he believes that regulation, not unfettered capitalism, should guide how products with such potential for abuse are sold, citing state-run alcohol stores (such as those in Canada and some US states) that blend a legal retail market with reasonable restrictions and price controls. Without such safeguards on substances such as cannabis and alcohol, legalized markets can simply incentivize firms to lower prices and cultivate unhealthy demand. “There’s no way to get rich on a drug without having someone abuse it,” Kleiman said. “Moderation is not profitable.”

Juul may disprove this. It could, theoretically, do just fine easing the world’s 1.1 billion or so smokers off cigarettes which will eventually kill half of them. “We’re not creating new consumers,” Monsees said. “We don’t need to hang on to our consumers.” He suggests Juul’s features will let users taper off cigarettes and, if they choose, eliminate their nicotine consumption over time. “We’ll support people as they pass through our product and not use it completely,” he claims. “That’s the best way to return value to our [private] shareholders.”

Yet Juul is not being marketed as the equivalent of a better nicotine patch. It’s sold and marketed as a product to be desired. It’s possible the price of saving today’s smokers from cigarettes may be enticing millions of adolescents to pick up a new nicotine habit. For some, it will become debilitating.

Lawsuits against Juul are already piling up. One is on behalf of 15-year-old identified as “D.P.” in a New York district court case filed in June (pdf). After trying Juul in September 2017, the high school freshman quickly grew hooked on nicotine, the case states. His parents switched him to a different high school, removed the door to his bedroom, closed off parts of his house, and asked school official not to let him use the bathroom unattended. But “D.P. is unable to stop Juuling,” according to the filing. “[He] became withdrawn, anxious, highly irritable and prone to angry outbursts…and begun to perform poorly at school.”

Parents worry about the addictive products Silicon Valley produces, from social media to games that keep all of us—especially teenagers—coming back for more. Now they can add chemical dependencies to the list.