It’s stronger than steel and paper thin, but graphene isn’t living up to its promise

If the film classic The Graduate were being made today, it’s likely that, in delivering his iconic line, Walter Brooke would lean into Dustin Hoffman’s ear and offer a new career path: “graphene,” instead of “plastics.” Perceived as the next big thing in science and technology, graphene, a super-thin layer of graphite, excites many with its promise of technological breakthroughs. It conducts both electricity and heat super-efficiently, while also being incredibly strong.

If the film classic The Graduate were being made today, it’s likely that, in delivering his iconic line, Walter Brooke would lean into Dustin Hoffman’s ear and offer a new career path: “graphene,” instead of “plastics.” Perceived as the next big thing in science and technology, graphene, a super-thin layer of graphite, excites many with its promise of technological breakthroughs. It conducts both electricity and heat super-efficiently, while also being incredibly strong.

In just the past few months, scientists at MIT have created graphene-based light sensors that can accelerate translation of infrared light to electrical signals, potentially speeding up optical data transfer on public and private data networks dramatically. A Stanford team used the helical structure of DNA to work out how to create graphene “ribbons” that could be used in semiconductors. Several teams have looked at using graphene to create more efficient solar panels, helping to boost solar energy production at lower costs. Even mistakes during graphene experiments yield possible innovations: researchers from Cornell and University of Ulm in Germany accidentally made super-thin glass, which could eventually be used in transistors.

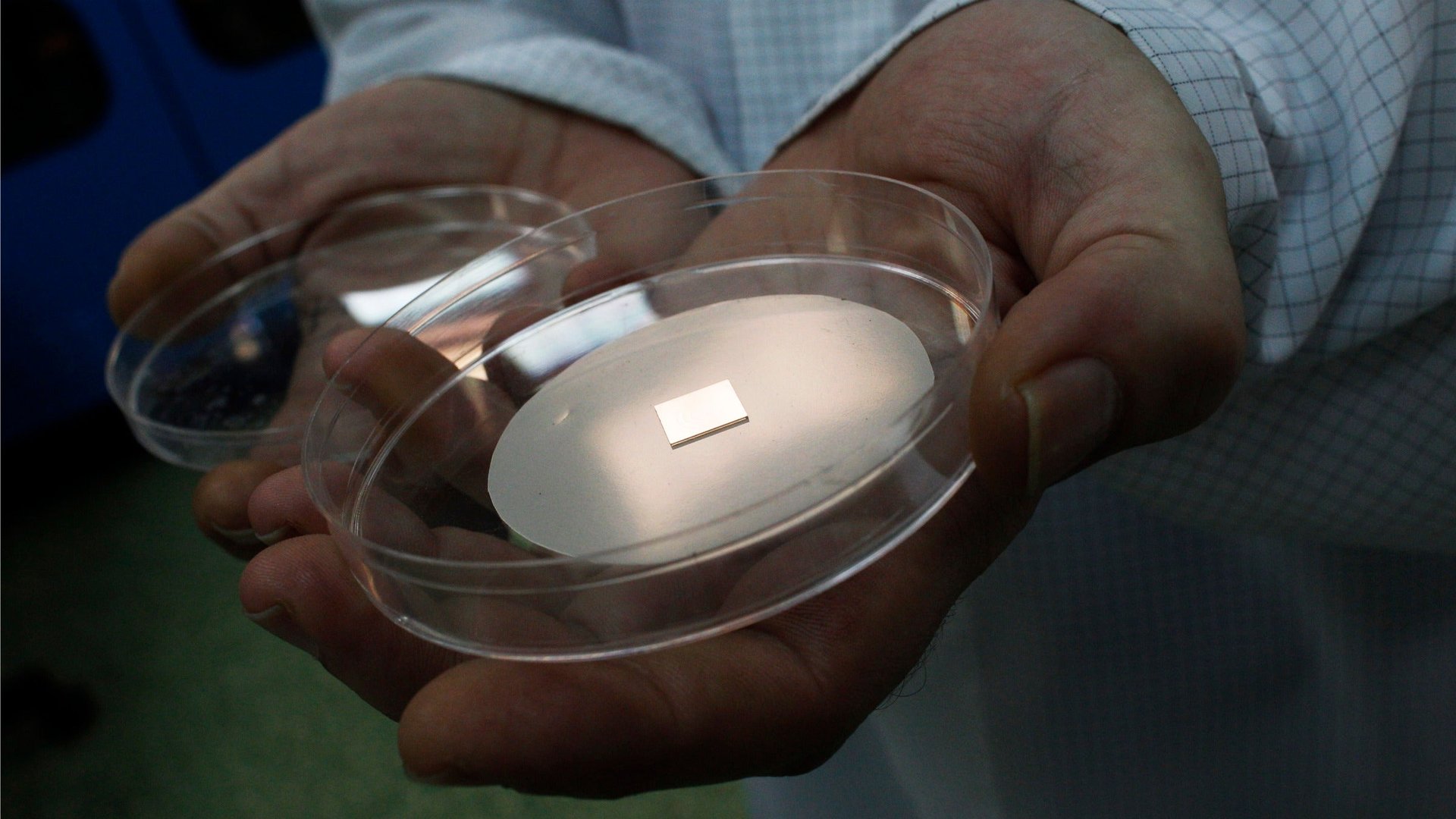

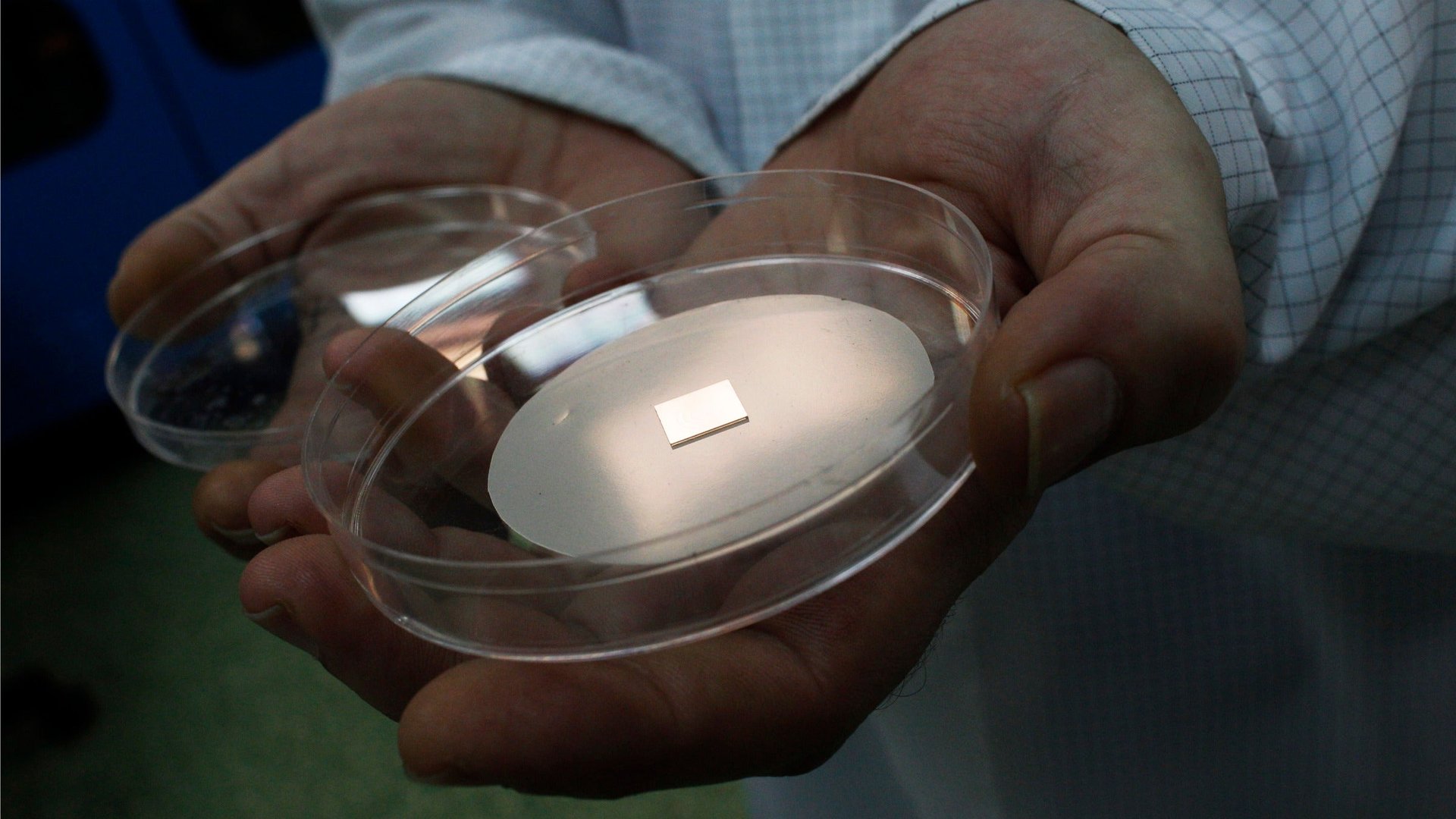

First successfully created by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov at the University of Manchester a decade ago, the material’s genesis sounds deceptively simple—Geim and Novoselov peeled off layers of graphite with scotch tape until they achieved the elusive single-layer thickness. Yet spinning it into an actual boom industry is proving to be frustratingly difficult.

Get your hot patents

The groundbreaking innovations being developed by the MITs, Cornells, Stanfords and elsewhere in academic and commercial research are just the first step in a long commercialization process. To protect their inventions while they work out the applications for them, institutes and corporations patent their breakthroughs, and patenting around graphene is white hot at the moment, an intense race to amass intellectual property in hopes of an eventual payoff.

As home to graphene’s first creators, the UK government poured £38 million ($61 million) into creating a National Graphene Institute at subsequent Nobel winners’ Geim and Novoselov’s alma mater in Manchester. According to a report (pdf) by the British government’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO), the number of overall graphene patents filed tripled from July 2011 to February 2013, reaching nearly 8,500 earlier this year. Over 3,500 were filed in 2012 alone, according to the IPO.

Turning graphene into a strategic asset is a little tougher. Despite the country’s push to make graphene research a strong enterprise, the UK actually sits at a joint 163rd position globally in patent families (patents taken out in multiple countries to protect a single invention) as of early 2013. As things stand, the Institute is not scheduled to open until 2015, which will then presumably boost the country’s languishing position in patent families rankings, but itself isn’t a silver bullet.

Today, the action around graphene development is mainly happening in Asia. Of the top 20 patent winners around graphene globally, four are in South Korea, (with Samsung in top position worldwide) and four in China, according to the IPO data. The highest US-based entrant is IBM at fourth position. Despite being home to its discovery, the UK doesn’t even make the top 20. The European Union has taken graphene on as a wider strategic investment as the European Commission proffered €1 billion ($1.4 billion) for graphene research earlier this year, to be spread among the region’s institutions, in order to keep its member countries in a lead position to exploit expected eventual payoffs from its development.

Put some graphene on it

Graphene researchers are finding that turning those patents and new possibilities into concrete realities is a tougher nut to crack. One problem is mass-production. Under most current production methods, graphene tends to fray at the edges and is challenging to produce in pure form over even a small area as graphene’s beneficial properties come from its symmetrical, honeycomb-like single atomic layer structure. With this fraying, graphene can become brittle and lose its vaunted strength as a material.

Production of pure graphene is not the only complication. A group of Brown University researchers have determined the super-thin and incredibly sharp edges can pierce lung or skin cells and possibly interfere with their function by rupturing cell membranes, creating toxicity concerns for the ultralight material.

On the positive side of the ledger, only small quantities of graphene are required to cover a large area. According to a new study by Cientifica (pdf) which looks at graphene investment, 20g of graphene material, dispersed in a liter of liquid could coat two standard soccer fields. Unlike most industrial materials, Cientifica’s Tim Harper and Dexter Johnson write in the study, to be useful, functional graphene needs only to be produced by the kilo, not the ton.

Better, faster, cheaper?

Finding things that graphene can do, however is different than finding things which graphene can do better. To be useful on a large scale, graphene needs to be easier to produce, at lower costs by a workforce trained to handle it. A recent ParisTech Review look at graphene put the cost of producing a gram of the material at around $800, compared to less than a dollar per gram for electronics-grade silicon. More importantly, however, Mark Goerbig, a graphene researcher and professor at France’s Ecole Polytechnique in Paris told the publication that it could take a generation to train engineers to work with the material in practical terms.

This hasn’t stopped investors, and those hyping investments, from salivating over this potential wonder phenomenon: One indication is the chatter on finance websites about graphene, even though many investors admit lacking meaningful knowledge about it, or having any sense of when it will come to fruition in commercial application terms. This enthusiasm-to-knowledge ratio has clearly excited graphene hucksters in the same way gold mania has over the past few years—doing a Google search for graphene prompts ads touting graphene investments, which is never a good sign. One website for “graphene investors” even claims the material is already being used by the Israeli army to make “invisible missiles,’ shouting “This is happening right now!” It isn’t.

Cientifica’s Harper and Johnson say the key to graphene will be what is often true with new innovations—getting production at sufficient scales down to a manageable cost, then finding applications that benefit significantly from its properties, which could include flexible touch screens, higher capacity storage batteries, or super efficient high-speed computing, all of which face structural hurdles posed in part by use of currently commercialized materials.

The patent race is an early indicator that some of the world’s biggest technology players have done the math and see long-term value in graphene. Though interest from companies such as IBM, Samsung, SanDisk, Foxconn and Fujitsu, all among the top 20 graphene patent holders globally, suggests the high profile graphene bets are in electronics and computing, it’s more likely that we will see graphene trickle out into less sexy areas like glass coatings, water filtration, special inks or solar cells—applications with a lower profile but potentially much larger market over time.

In the meantime, though, the biggest winners may be crackpots looking to part unsavvy internet investors with their savings.