China is investing more than ever in science, but it’s not paying off

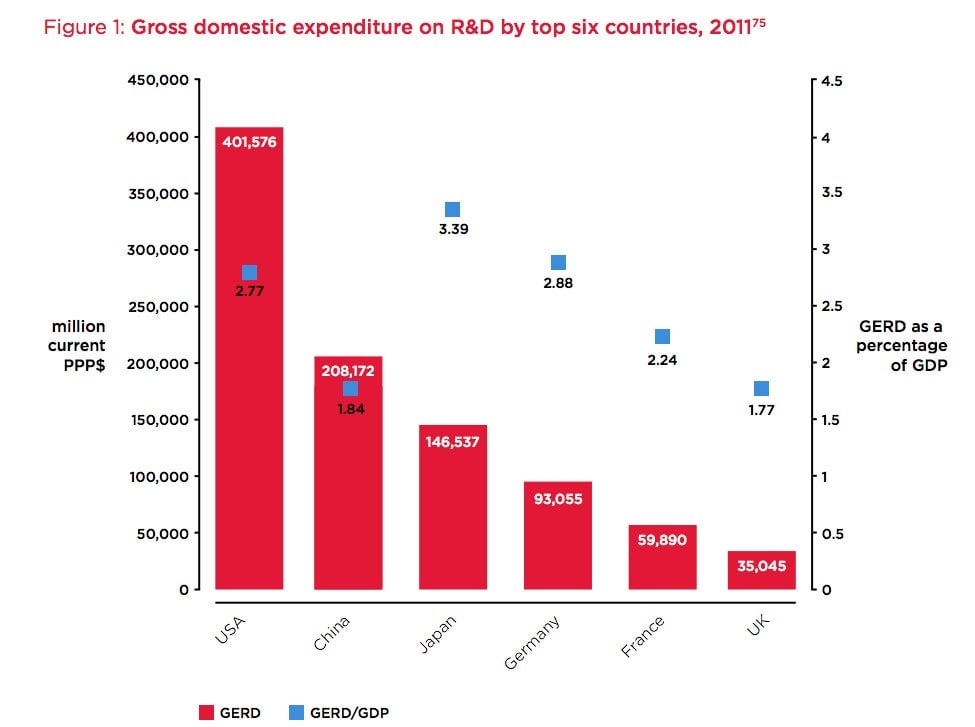

Last year, for the first time ever, China’s spending on experimental research exceeded 1 trillion yuan ($163 billion). China’s state research and development spending has grown around 18% each year since 2008 (pdf, p.18), but that’s apparently not good enough: China now aims to boost R&D spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2020 (pdf, p.2), from its current 1.1%. Some think China will overtake the US as the world’s leading science producer (paywall) as early as 2020, or even sooner.

Last year, for the first time ever, China’s spending on experimental research exceeded 1 trillion yuan ($163 billion). China’s state research and development spending has grown around 18% each year since 2008 (pdf, p.18), but that’s apparently not good enough: China now aims to boost R&D spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2020 (pdf, p.2), from its current 1.1%. Some think China will overtake the US as the world’s leading science producer (paywall) as early as 2020, or even sooner.

That’s not especially surprising considering that US government spending has withered to just 0.8% of GDP, or $966 billion, the lowest level in 40 years. And unfairly or not, many in the world view Chinese scientists as a threat. A recent example is the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which, citing worries about national security, banned Chinese astronomers from a recent conference on the highly sensitive topic of alien planets.

But hold on a minute—not all of that 1 trillion yuan is actually going toward research. In fact, only 40% is, reports China Economic Weekly, via Want China Times. The rest of it—600 billion yuan ($98 billion)—was spent on things like travel and business lunches, say officials. That’s a lot of in-flight Wi-Fi and filet mignon. (For its part, the US government slashed at least $600 million in spending on conferences last year, after some federal workers were busted for boondoggles.)

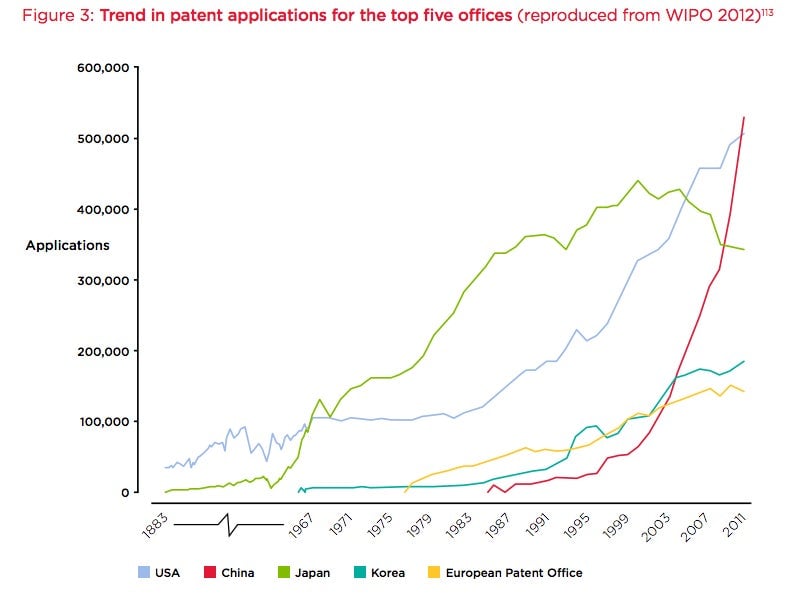

What else is China spending on? China’s patent applications have soared of late, probably thanks in large part to financial incentives designed to hit the government target of two million patent applications by 2015.

This approach has “unsurprisingly, favored quantity over quality,” as Guy de Jonquières, a fellow at the European Centre for International Political Economy, explains in his excellent overview of the issue (pdf). Of China’s 2011 patent applications, fewer than one-third were for “innovation” patents; the rest covered tweaks to existing technology or new design standards. As de Jonquières flags, in 2011, China collected $1 billion in patent royalties, but paid $18 billion in patent royalties to other countries. That $17 billion deficit compares with a $82 billion surplus on patent royalties the US claims each year.

R&D spending and patent development are two of the three big metrics for evaluating a country’s science competitiveness. The last is publication in scientific journals. China has really proven itself here, based on Thomson Reuters’s Science Citation Index (SCI). China now claims a nearly 10% share of the global output of scientific papers, reports the Economist.

But China invites suspicion in this arena too. The government has strategically launched more than 200 English-language international academic journals, as Australian Financial Review reports (paywall), which claim to abide by strict international peer review standards. However, the ultimate say in content falls not to peer scientists but to the Communist Party secretary of the Chinese institution sponsoring the journal, who is obligated to police content for anything that might conflict with Party values. Meanwhile, academic fraud in China is rampant; police recently busted a $500,000 trade in plagiarized articles and fake academic journals, reports The Economist.

China is certainly closing the innovation gap with the US. But innovation tends not to respond to command-economy policies. Regardless of how much it spends, patents or publishes, China must first fix many things before it can hope to close that gap completely.