There could be slaves in the supply chain of your chocolate, smartphone and sushi

Forced labor is a reality, and you might be using products made by workers who had no choice in the matter.

Forced labor is a reality, and you might be using products made by workers who had no choice in the matter.

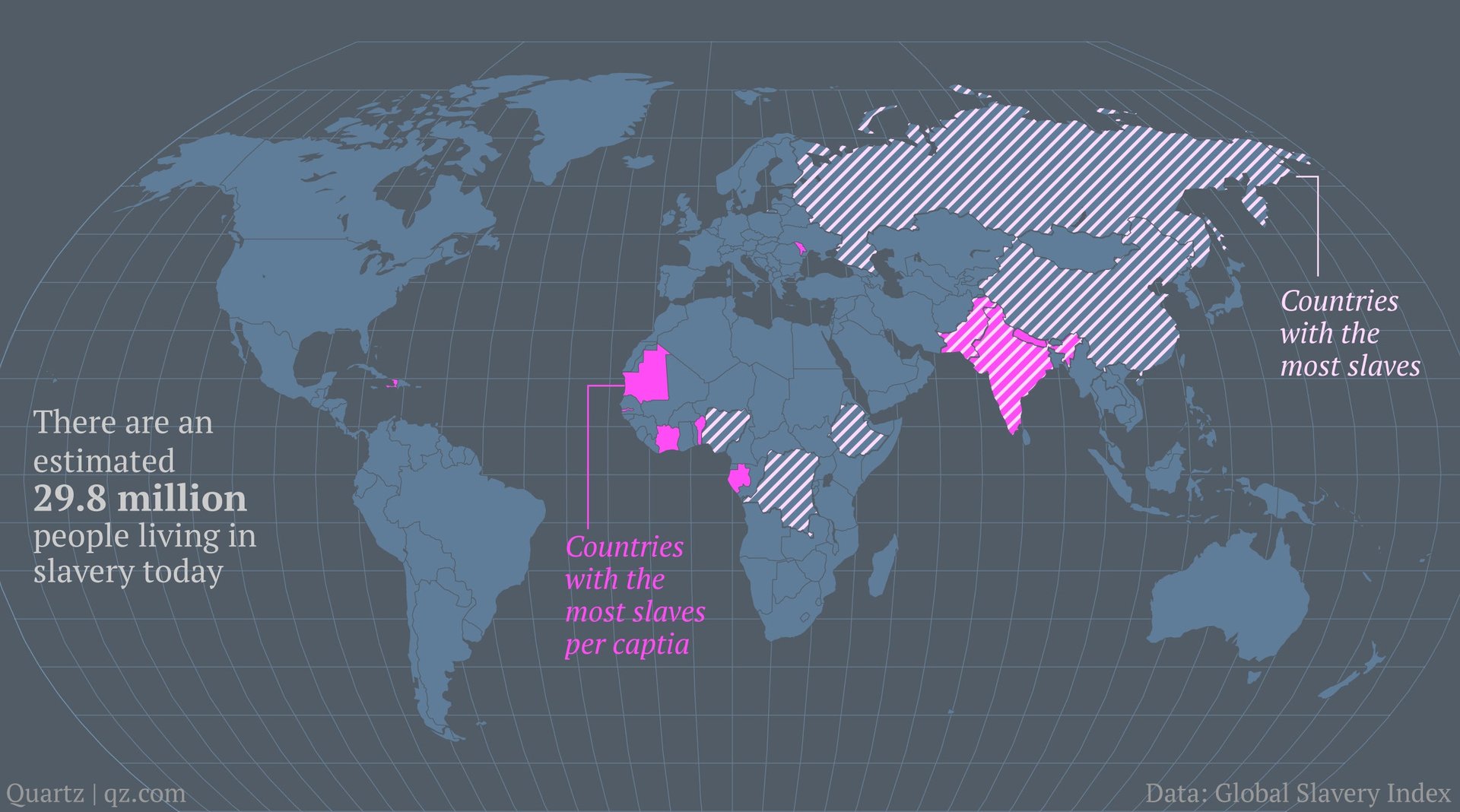

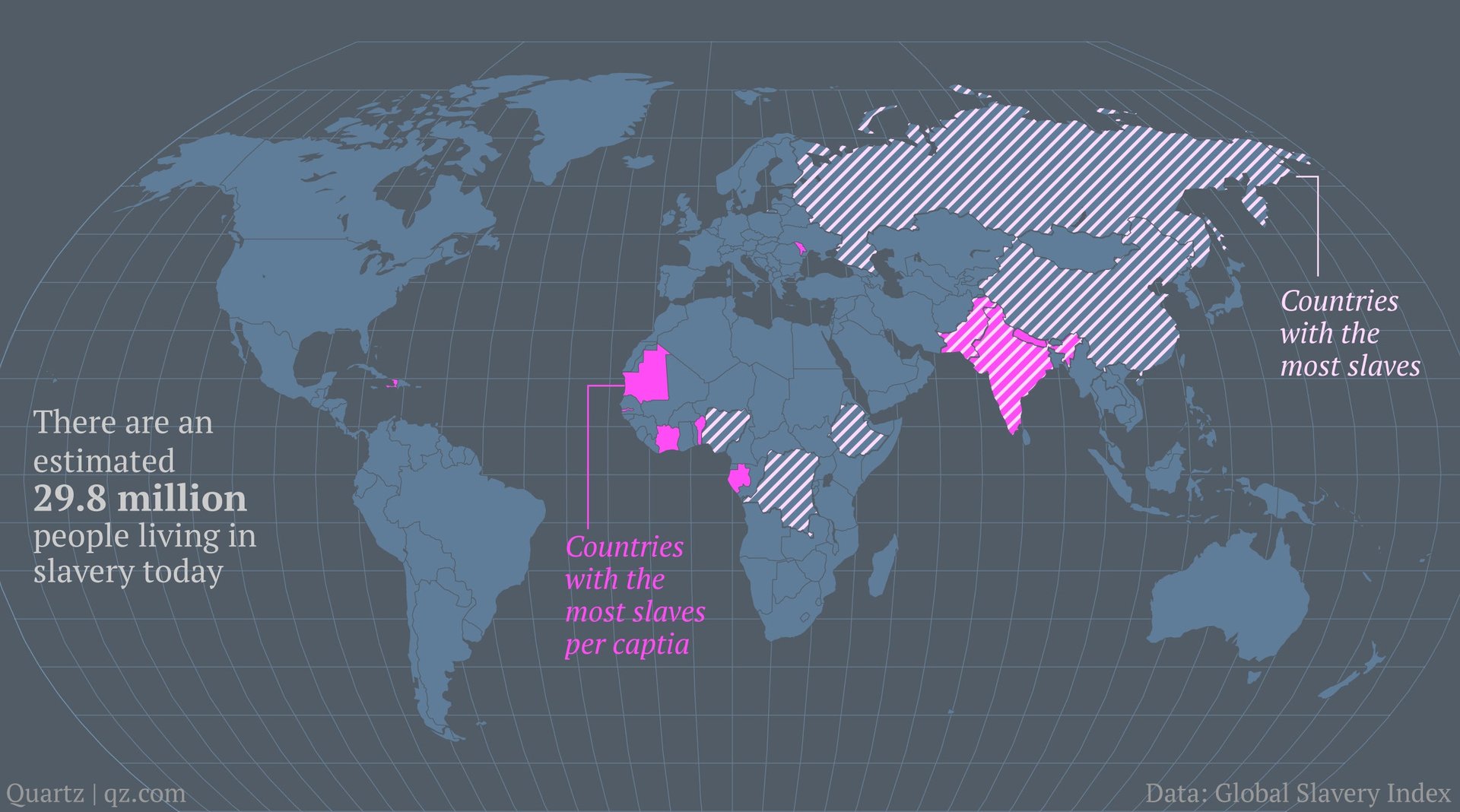

The first edition of Global Slavery Index from the Walk Free Foundation, an anti-slavery NGO, estimates that there are 30 million slaves in the world—and more than half of them are in prominent emerging markets like India, China, and Russia.

Modern slavery, as the index defines it, includes all kinds of forced labor, ranging from hereditary bondage in Mauritania, which has the largest slave population per capita in the world, to forced sexual exploitation, including the arranged marriage of minors. Most of the countries where slaves make up a significant slice of the population have a cultural tradition of bonded labor, like Haiti’s restavek system of indentured servitude for children (which can be an innocent way for families to help each other out, the report says, but is often abused).

But the largest form of forced labor is in private industry, where about two-thirds of people working in slave conditions—usually forced or bonded labor—are found. That’s why this new effort to measure global slavery exists: It’s part of a campaign funded by the chairman of one of the world’s largest miners, Andrew Forrest of Fortescue Metals Group, who wants companies to eliminate slavery from their supply chains. As global trade has led firms to source materials and labor from ever more far-flung locales, it has become easier for them to turn a blind eye to who makes their products. Here are just a few examples:

- This summer, an Australian man imprisoned in China reported that prisoners were making headphones for global airlines like Qantas and British Airways. Some 300,000 sets of the disposable headphones were made by uncompensated prisoners who were forced to work without pay and regularly beaten. The index says that there are about 3 million slaves in China, in state-run forced labor camps, at private industrial firms making electronics and designer bags, and in the brick-making industry.

- Companies like Apple, Boeing and Intel—among thousands of others—have been under pressure to document that the tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold they use aren’t being mined by slaves in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a civil war has led armed groups seeking funding to force civilians to work. The US Securities and Exchange Commission adopted a rule forcing American firms to trace the minerals they use to their origins, and while business lobbies have sued to overturn it, industry leaders have begun planning to file the first required reports in May 2014.

- In the Asian seafood industry, migrant workers may become forced laborers who harvest and prepare mackerel, shrimp and squid bound for markets around the world.

- Côte d’Ivoire is the world’s leading supplier of cocoa—some 40% of the global supply—and much of it is grown and harvested by some children engaged in forced labor. In 2010, Côte d’Ivoire said 30,000 children worked on cocoa farms, although Walk Free’s index estimates as many as 600,000 to 800,000. While this has been widely reported on since 2000, and the global response has been strong, compared to that of other allegations of forced labor, the problem has not really been solved. As of 2012, 97% of the country’s farmers have not participated in industry-sponsored campaigns against forced child labor. Mondelēz International, the world’s largest chocolate producer, which owns brands such as Milka, Toblerone and Cadbury, has struggled for years to take forced labor out of its supply chain. It committed $400 million to a program aimed at creating a sustainable cocoa economy last year, but its efforts have been ineffective so far.

Many of the countries in the map above are not party to international human trafficking treaties or simply don’t enforce them. Many of the companies that use labor in those places have weak supply-chain policies in place. The goal of Forrest’s group, inspired by Bill Gates’ data-centric philanthropy, is to make slavery easy to quantify, and thereby pressure international companies not to put up with it.