Wall Street’s beating up on Netflix again, but this thriller has a great hero: the customer

So Netflix got downgraded again? Lost a chunk of its market cap when its stock plunged? And all because Wall Street is worried that the online rental service’s spending, as well as competition from a larger, better-capitalized rival will capsize its delicate subscription model?

So Netflix got downgraded again? Lost a chunk of its market cap when its stock plunged? And all because Wall Street is worried that the online rental service’s spending, as well as competition from a larger, better-capitalized rival will capsize its delicate subscription model?

Yesterday, Netflix fell hard as Bank of America analysts downgraded the stock, tumbling 11% to close at $65.53—its biggest drop since July.

This comes on the heels of Macquarie’s Sept. 17 “underperform rating,” which also warned clients that content owners such as Time Warner and CBS “rule the roost.” After all, they do have a larger marketplace to shop their streaming rights–a marketplace Netflix was able to invent only because the studios were too dense to see the revolution in digital distribution coming until it was too late.

VentureBeat piled on late last week, warning that Netflix chairman and CEO Reed Hastings was wrong in a recent interview to dismiss Amazon’s video streaming service, Amazon Prime, as “a mess.” Apparently the e-tailer’s global customer base, diverse menu of products and deep pockets would trump Netflix’s know-how and agility should a battle for streaming subscribers turn long and ugly.

Really?

I’m much too young to feel this damn old—like I’ve seen it all before. But I have. And it is exasperating that the market doesn’t know any better.

So let’s recap: Netflix is attracting subscribers like a giant magnet, and riding high in Wall Street favor, its stock hits an all-time high even as larger and better capitalized rivals—including Amazon—lurk on the sidelines waiting to steal the model Netflix invented. Management raises prices on Netflix’s most popular service to invest in technology upgrades and more movies.

Cue angry subscriber defections, stock plunge, Wall Street forecasts of doom and demise. More stock losses as Hastings intransigently positions Netflix to run without profit as he chases an expansion that investors consider ridiculous.

This all happened in 2004 when a much smaller and not entirely profitable Netflix took on Blockbuster Online. And we all know how that turned out.

Netflix does one thing—rent movies—and, as Hastings always maintained, it is determined to do that better than anyone else on the planet. Add desperation and laser-like focus and not only do you have the ingredients for winning an internecine struggle for market share, but the recipe for revolutionizing an industry—again.

The parallels to 2004 are remarkable: Blockbuster, the theory ran, would quickly crush Netflix by drawing on its 50 million store users (20 million of them active) to populate its new online rental service, and Blockbuster’s standing in the movie industry and vast capital reserves would allow it to out-market Netflix and cut better deals for its DVD inventory.

Same deal with Wal-Mart, which made a weak foray into online rental to protect its huge DVD sales. Amazon, then quietly negotiating for content to launch its own US rental operation, posed what Hastings considered the supreme threat–a gigantic and growing customer base and the technological know-how to beat Netflix on its own turf.

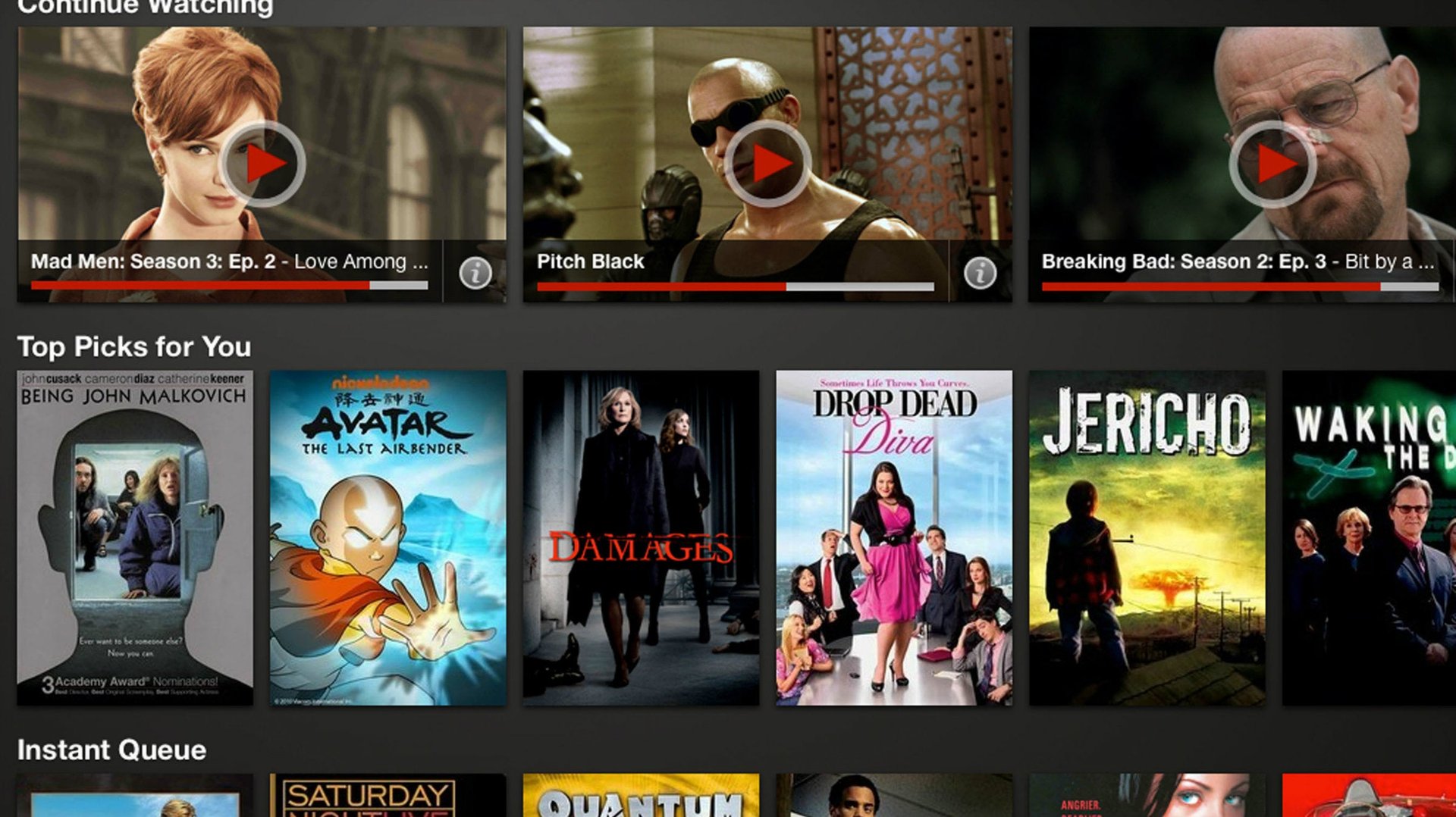

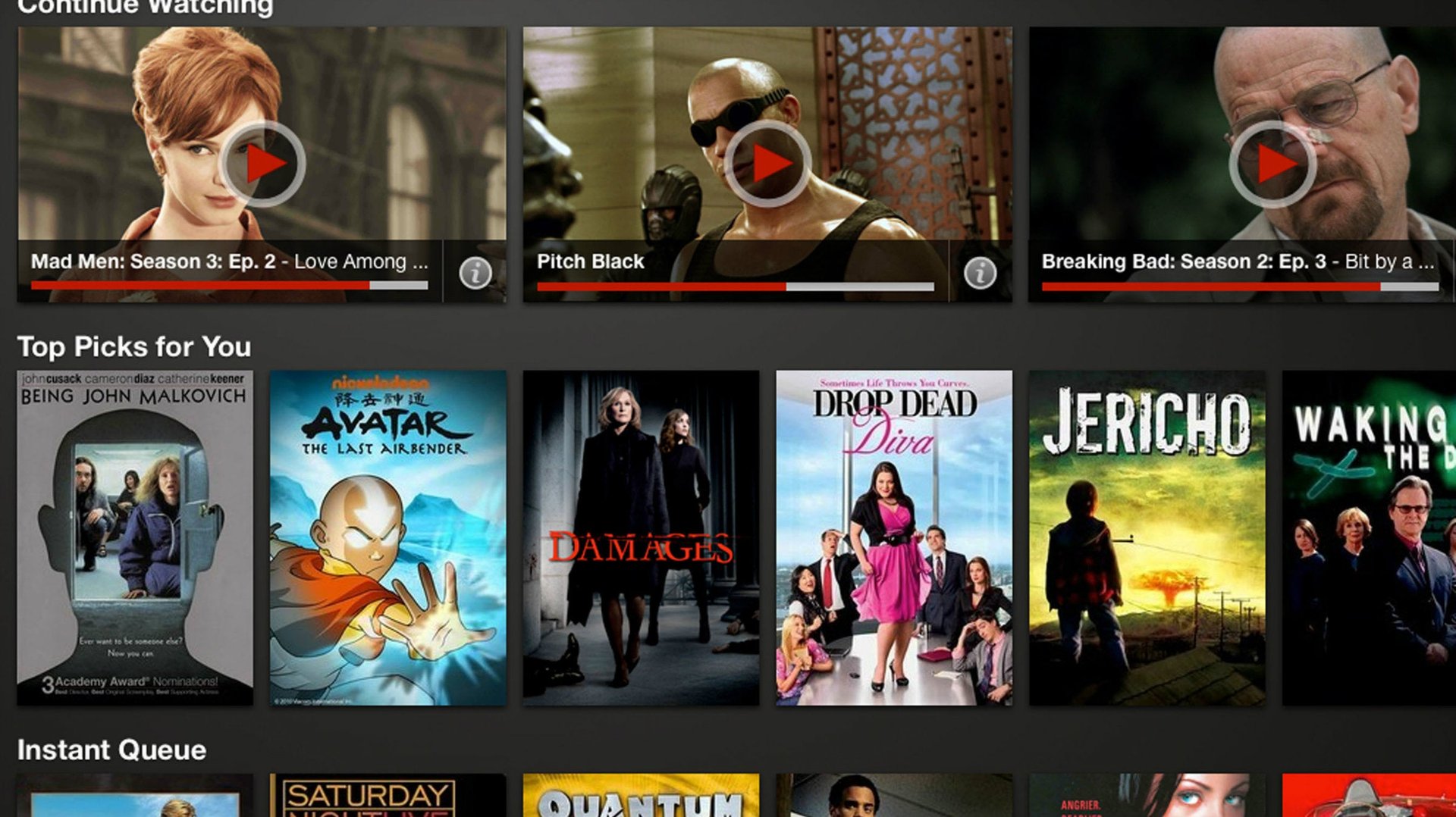

But the main element that was overlooked in the equations proved the most critical—consumers. Netflix won because its mission is bred into the very bones of its web platform and its corporate ethos. Netflix built a consumer-focused operation from the ground up to respond to what customers want and how they actually behave, no matter how irrational or inconvenient. The Netflix web site is essentially a highly instrumented market research platform that has allowed the company to track, analyze and project consumer behavior around entertainment consumption for 15 years.

This data helped Hastings understand that first-run movies were not essential to his product mix (70% of his rentals were back-catalog titles), that consumers had no problem tapping different rental services for different “use occasions,”and that this behavior posed no threat to Netflix’s subscriber retention.

This is how—regardless of its cash-on-hand or the population of the competitive landscape—Netflix is likely to prevail in the next world of home entertainment.

Blockbuster died through a slow unraveling of a business model that served the bottom line rather than customers and tolerated a relationship known within the company as “managed dissatisfaction.”

I see the same circumstances arising over streaming—with the studios and cable companies taking their accustomed places as drags on distribution innovations that threaten cable subscription. This obstructionist play did not stop streaming from getting huge and it certainly won’t stop the advent of a cable-less land where each consumer assembles his own menu of content purveyors from an online marketplace similar to Apple’s App store.

Hastings envisioned this more than half a decade ago. By watching his customers and analyzing his data, he could see that there would be room in this new world for both subscription and a la carte content purveyors because consumers continue to do both simultaneously. And that’s why, when they can’t find a first-run movie on Netflix, they simply switch to Apple’s iTunes or Amazon Prime with no idea of canceling their subscription to either.

The only potential threat is that Hastings is facing this new set of foes without his experienced and multifaceted executive team—individuals who kept check on his ego and brought much-needed consumer empathy to Netflix. And that’s a quality that Hastings, for all his engineering genius, simply does not possess—a failing he may refuse to concede.