If Healthcare.gov had been a commercial startup, it would have looked like this

With Wednesday’s passage of the deal to end the US government shutdown and lift the debt ceiling, we’ve formally stepped back from the brink of fiscal apocalypse, at least until Jan. 15.

With Wednesday’s passage of the deal to end the US government shutdown and lift the debt ceiling, we’ve formally stepped back from the brink of fiscal apocalypse, at least until Jan. 15.

It’s clear now that if the shutdown hadn’t occurred, the past two weeks would have been dominated by public and media reaction to the technological failures of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) online exchanges, potentially doing more to advance the GOP’s anti-ACA agenda than anything it might have won legislatively.

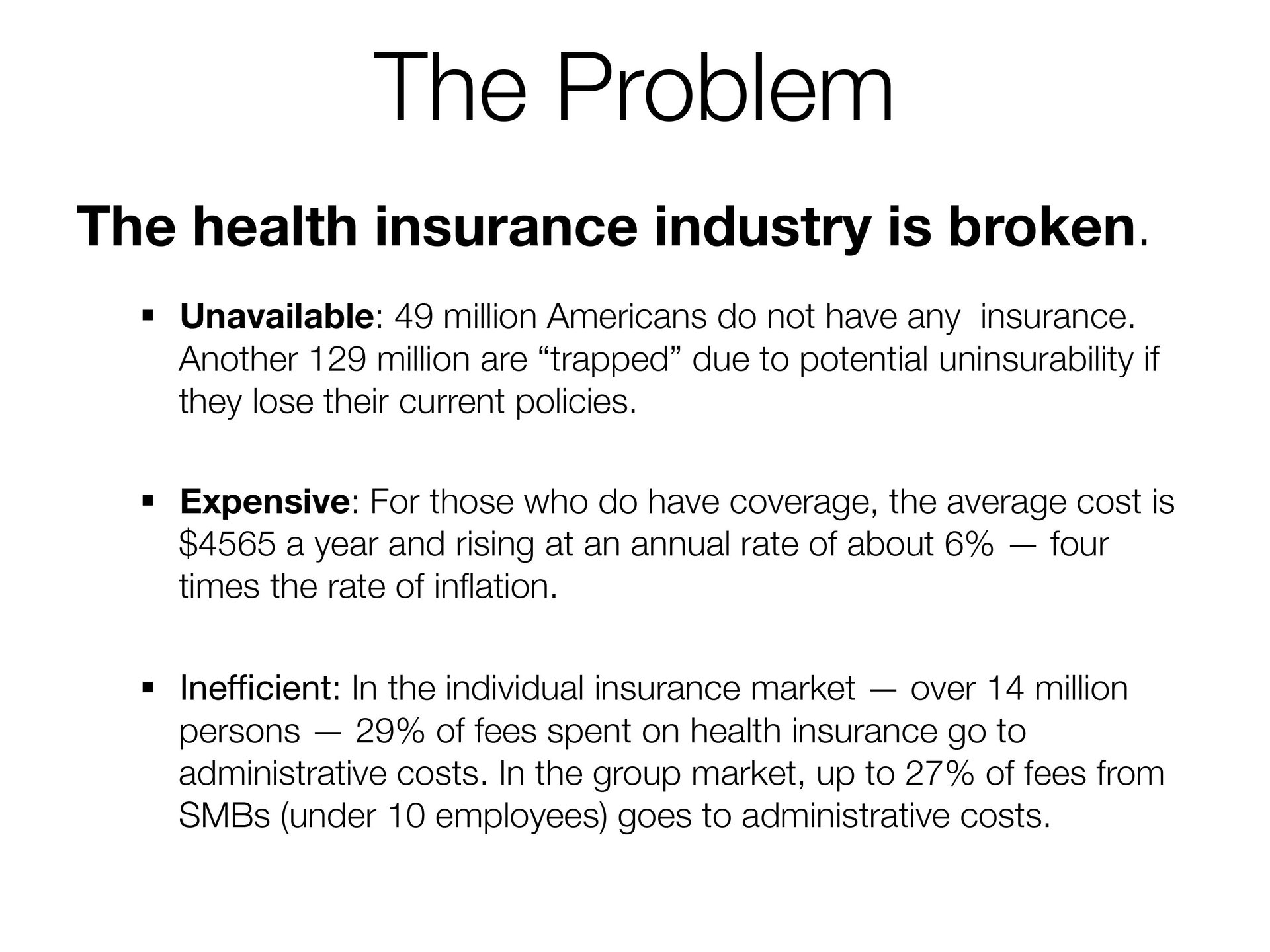

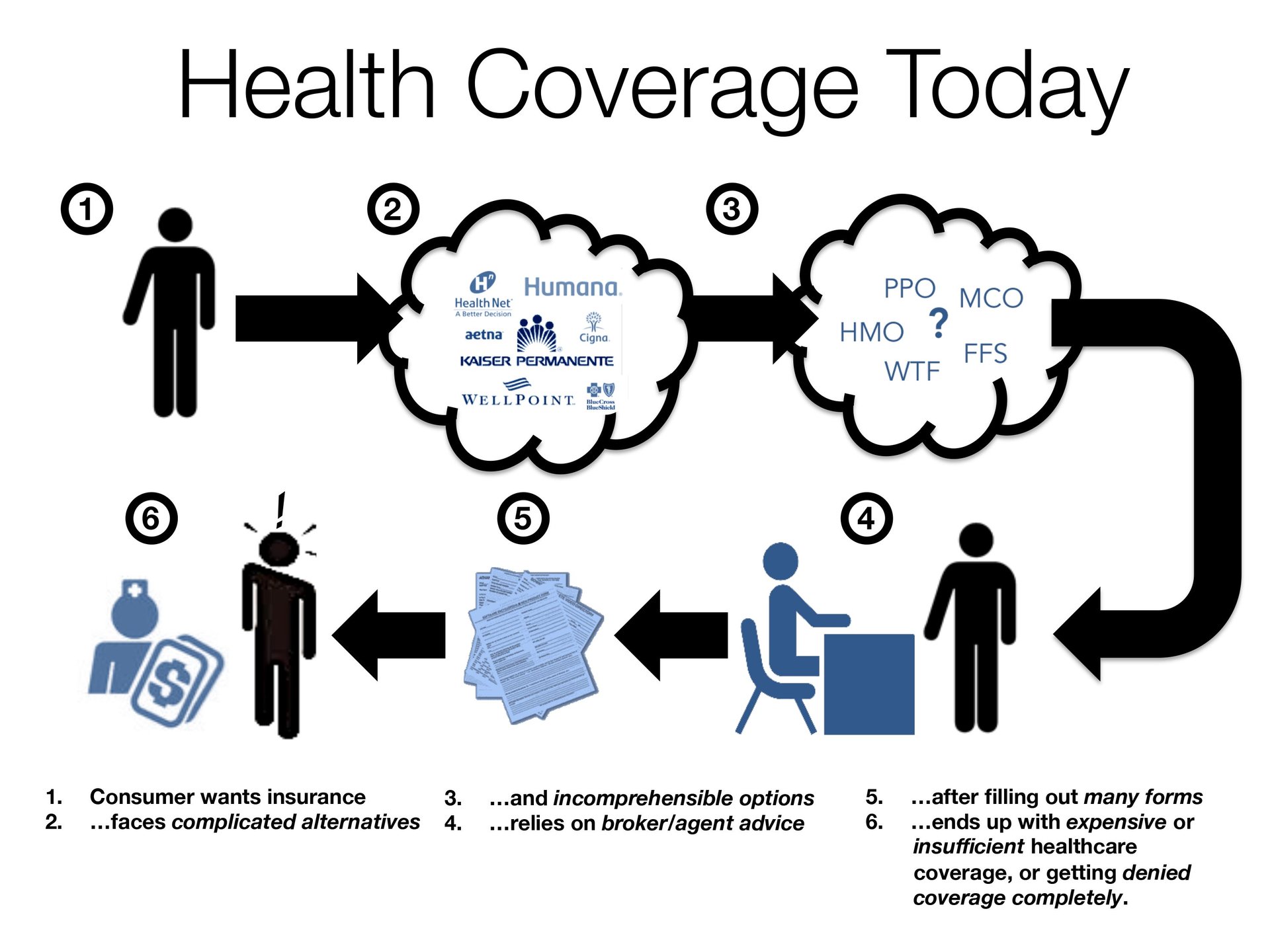

And let’s be absolutely frank here: These failures are real, and they’re spectacular. Nearly 10 million people visited Healthcare.gov, the federal site that serves as the health insurance purchasing portal for residents of the 36 states that refused to build their own exchanges. Of these, 3.72 million attempted to register profiles with the site; just over a million succeeded in doing so; only 271,000 managed to log in after registration, and only 36,000—less than 1% of users—managed to actually purchase insurance.

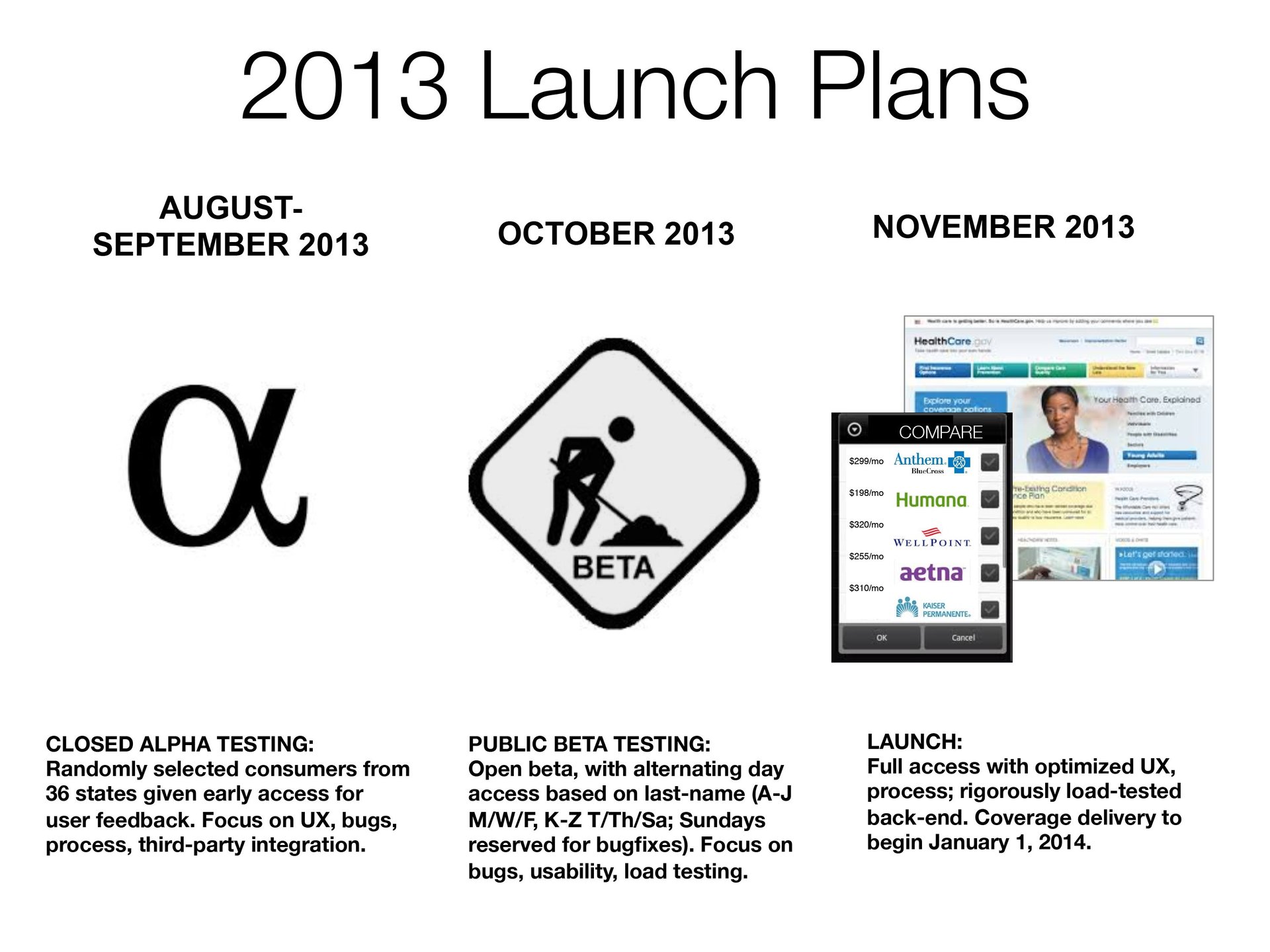

The Obama Administration was quick to note that it was still early in the process, and plenty of time remains for people to sign up before coverage begins on January 1, 2014—and certainly before open enrollment ends on March 31. It was, however, too slow to admit that there were fundamental flaws in the exchange infrastructure’s code and hardware setup—flaws that greater transparency in the development process might have exposed earlier, before they became fatal. And while there’s now a concerted effort to stamp out the bugs and deliver on the site’s promise of quick and easy access to affordable care, the terrible first impression users encountered is undeniably a threat to Obamacare’s potential success.

The president was quick to respond to detractors by making a pointed comparison between the Obamacare rollout and recent high-profile tech launch. “With every new product rollout, there are going to be some glitches,” he said. “Consider that just a couple of weeks ago, Apple rolled out a new mobile operating system, and within days, they found a glitch, so they fixed it. I don’t remember anybody suggesting Apple should stop selling iPhones or iPads or threatening to shut down the company if they didn’t.”

It’s possible that the president has been presented with so many false equivalencies that he figured lobbing one of his own wouldn’t matter. But comparing Apple’s handful of bugs with Obamacare’s technology meltdown isn’t just comparing apples to oranges, it’s like comparing apples to a punch in the face.

Imagine if only 1% of calls made on an iPhone connected. Imagine if Google only provided results for 1% of searches. Or Amazon only shipped 1% of purchases to the right customer. For a commercial venture to achieve a 99% failure rate even during beta testing would be a sign of imminent doom.

Of course, Obamacare isn’t a commercial venture. And in fact, a commercial venture would never have faced many of the issues that have contributed to its problems—including oversight by bureaucrats who are not technologists; questionable procurement tactics; an impossible release schedule and, most of all, sustained, overwhelming attempts at sabotage by entrenched and hostile forces from within the government itself.

Which brings up the question: Why isn’t Obamacare a commercial venture? Or more precisely: Given the fact that the Affordable Care Act is already a market-based solution that relies on guiding users to private insurers, why did the administration decide to build and run the massive federal healthcare exchange itself?

There’s plenty of precedent for outsourcing the building and maintenance of key infrastructure to commercial entities. In fact, at the state level, this has been done with everything from roads and bridges to yes, hospitals and clinics. The problem with simply privatizing such institutions, however, is that often this ends up sticking the public with long-range costs and no underlying assets. It can end up as a devil’s bargain, in which a commercial enterprise with no incentive to serve a community has control over the operation and revenue stream of a critical public good.

A middle ground does exist, however. So-called “public social private partnerships”—PSPPs—bring together commercial and public interests in what ideally ends up as a mutually beneficial collaboration. A government wants to build a certain piece of infrastructure, but doesn’t have the fiscal resources or the political consensus to do so. Instead, it turns to private sources for funding, development expertise and operational management, extending a long-term franchise over the infrastructure to these commercial partners, while reserving a substantial public stake in the venture. This gives it leverage to ensure that the core social good is properly preserved, and provides it with upside if the venture is run in a sustainably profitable fashion.

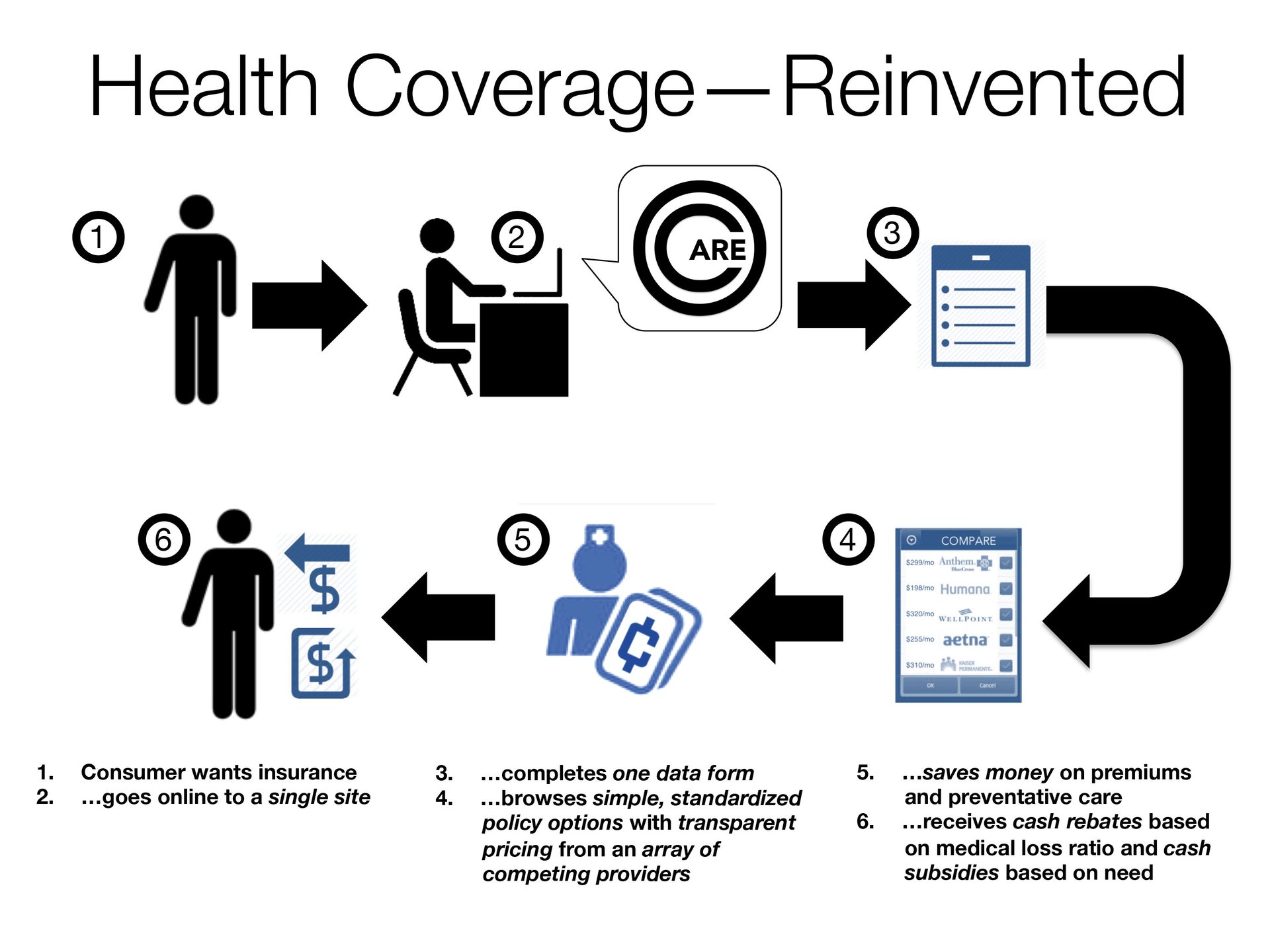

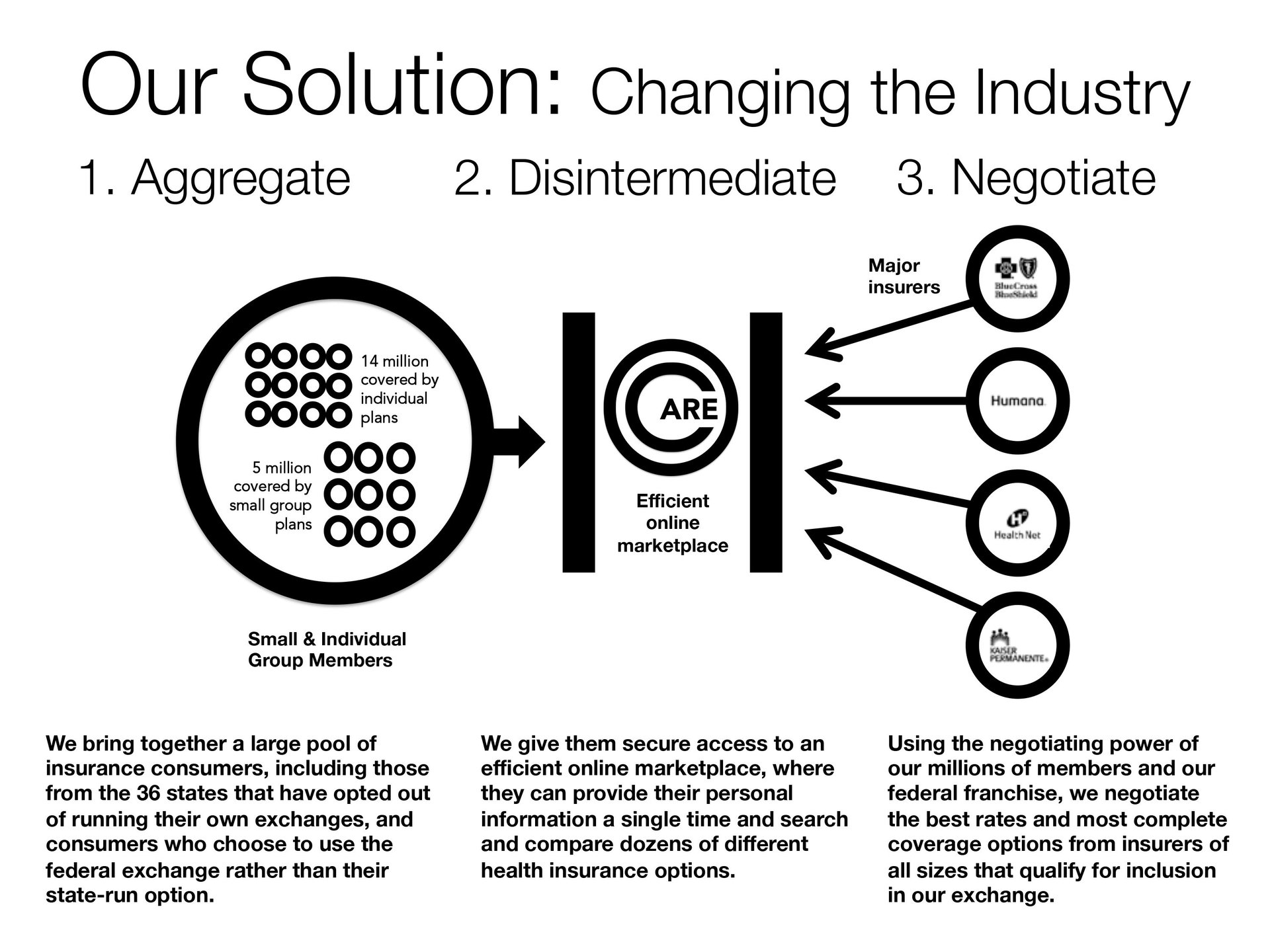

So, imagine that the Obamacare federal health exchange—we’ll call it OCARE for short—weren’t a government-run boondoggle, but a government-seeded commercial enterprise, tasked with developing and supporting a simple, efficient, frictionless marketplace for health insurance.

The federal government would still enforce the mandate that everyone buy insurance (either via the OCARE exchange, a state exchange or directly through employers). It would still provide the subsidies that allow low-income individuals to afford insurance. And it would still own a majority stake in this private enterprise, kind of like its ownership of massive stakes in AIG and GM after the post-banking crisis bailouts. But it would no longer directly be in the business of coding and managing consumer-facing websites—something that private, market-driven enterprise is much better equipped to do.

What would the private investors get? For one, a 30-year renewable franchise to be the “official” providers of the US National Healthcare Exchange. And just like with every commercial marketplace, from eBay to Orbitz, a percentage of all insurance sales through the site would go to the enterprise operating it. With some 20 million individuals being incentivized by law to purchase insurance, and some huge percentage of these going through the OCARE exchange, that’s potentially an enormous torrent of money.

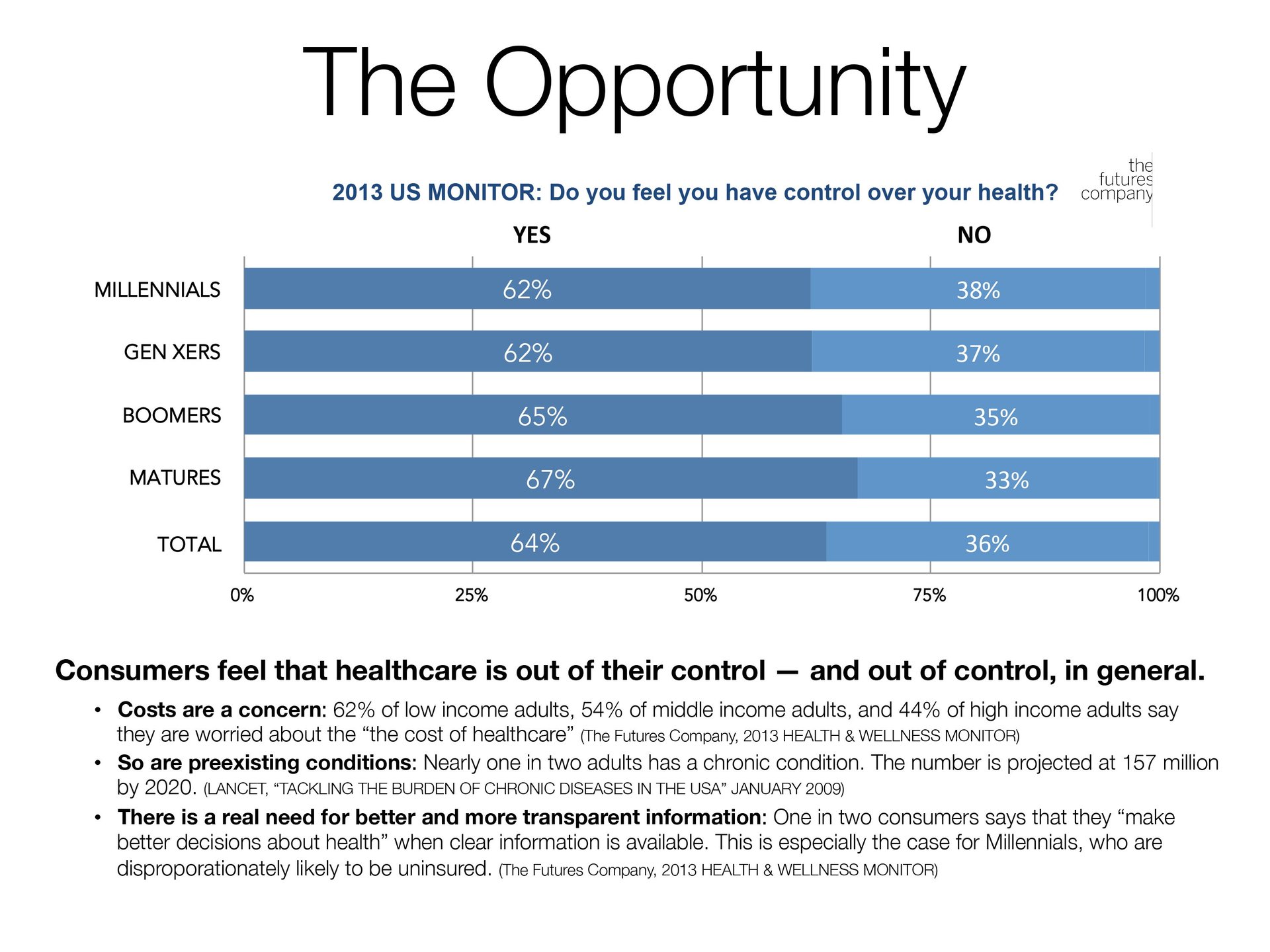

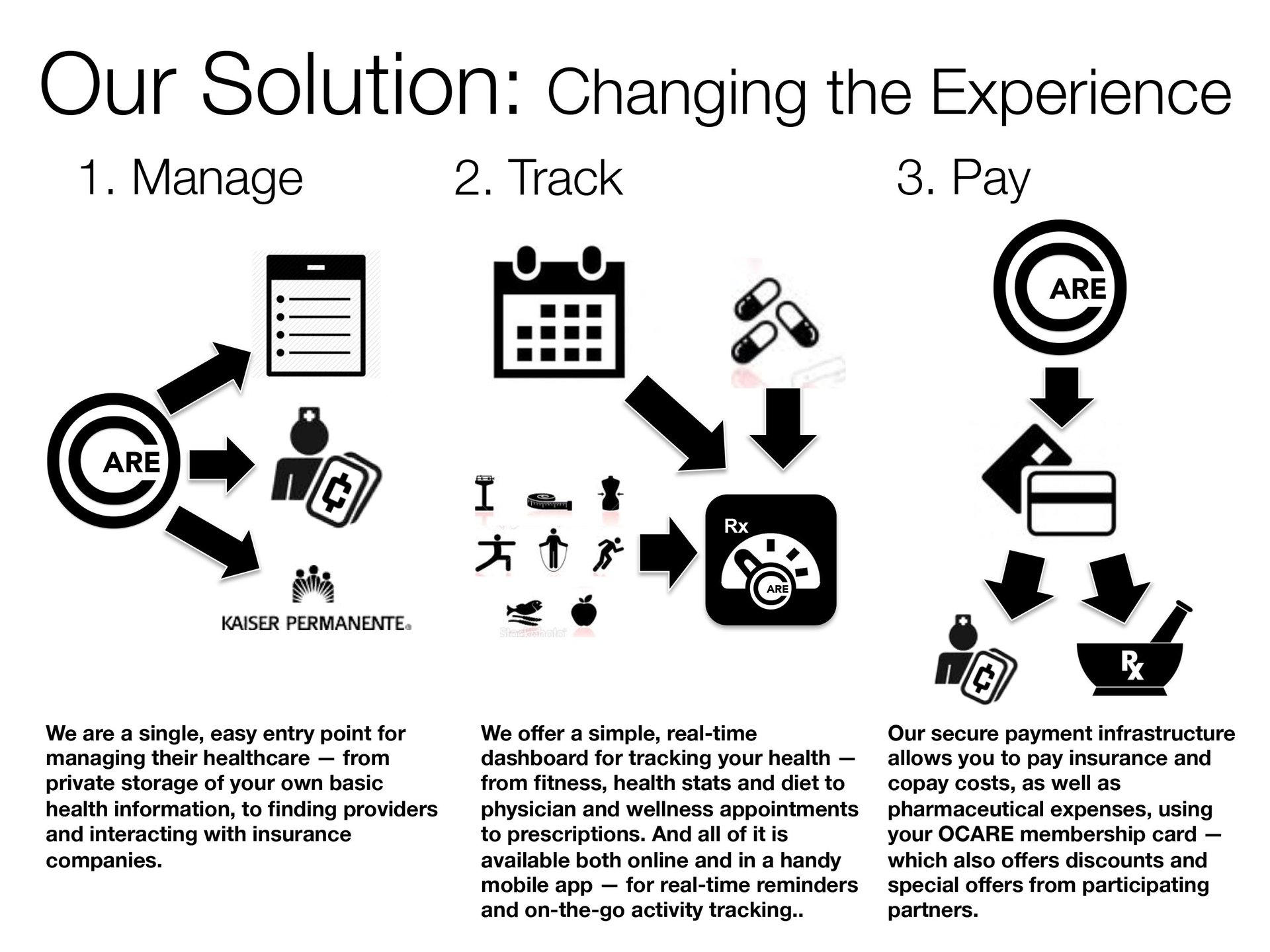

And that would just be the beginning of the OCARE opportunity. “If Obamacare were a privately launched enterprise, I could see it being something like a conglomerate of a health insurance marketplace plus data analytics plus health IT company,” muses Judy Wang, founding hacker of MIT’s Hacking Medicine initiative, which aims to help seed and foster disruptive healthcare enterprises.

She notes that another aspect of ACA is a major push for data-driven medicine, which would give OCARE the chance to build tools to explore trends in patient outcomes and help providers collect useful information to make care more efficient. And she also points out the vast and growing opportunity to create innovative mobile platforms for health management, which Obamacare encourages and which a commercial OCARE would be particularly suited to offer, given its unique access to consumers at the onramp point to obtaining care.

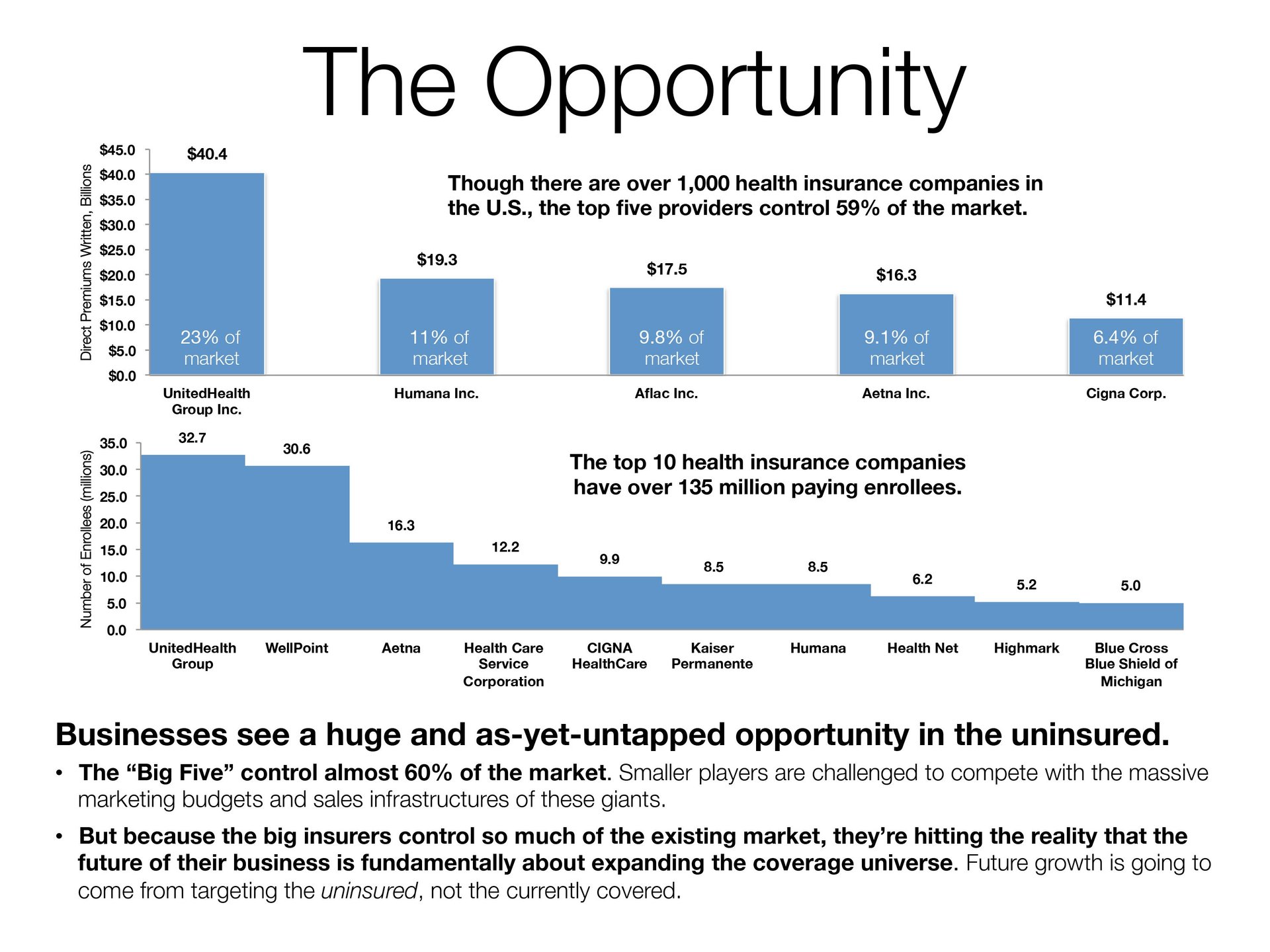

In fact, the more you look at it, the more straightforward the OCARE pitch would be: OCARE a large-scale aggregator of demand for healthcare needs, an empowered negotiator with healthcare providers, and an efficient online platform for bringing those two together in ways that offer both sides clear and obvious benefits. Presented this way, it even seems like a commercial version of Obamacare might have won support from some of the very forces that fought the fully public version tooth and nail. After all, it would be hard to pin a privately backed enterprise that manages an online marketplace with the label of “socialism.”

But Obamacare isn’t socialized medicine either. It’s a market-based system that guides people to purchase privately issued health insurance. And that points to another justifiable criticism of the Obamacare sausage-making process: The terrible job the administration did of telling the story of what the law would do, how it would benefit Americans, and how it would change society for the better.

Once again, a significant amount of blame can be applied to the messaging clumsiness of bureaucrats, as well as the political constraints surrounding the enactment of the law. And once again, a commercial enterprise would have almost certainly done a better job, in part because it would have needed a clean, simple and compelling way of marketing itself to investors long before it even opened doors to users.

“I am definitely concerned that the tech implementation sucked. But I absolutely would’ve placed more of a focus on how it puts the patient in charge of their healthcare, how they get it, who they choose to buy insurance from,” says Wang. “I think I’d still do that now! And I’d illustrate a lot of the great things that are coming out of the ACA—the fact that there are all these cool tools to help you determine what is best for you and your family.”

Given that we’re taking this flight of fancy, I decided to put together a pitch deck for OCARE—telling the Obamacare story from the vantage point of a parallel reality, in which the program is a commercial eHealth startup, seeded by government but managed by private business.